Xia Le:China is Looking for New Monetary Policy Tools in the Liberalized-Interest-Rate Environment

2016-03-14 IMIChina wrapped up its decades-long process of interest rate liberalization last October as the People’s Bank of China (PBoC) announced the lift-off of deposit rate caps and give banks full liberty of determining interest rates they offer to their borrowers and depositors. Although the authorities still need to do plenty of work to eradicate financial repression in China, the full liberalization of interest rate has marked an important moment for China’s financial liberalization, which includes other elements such as exchange rate reforms, capital account opening as well as RMB internationalization.

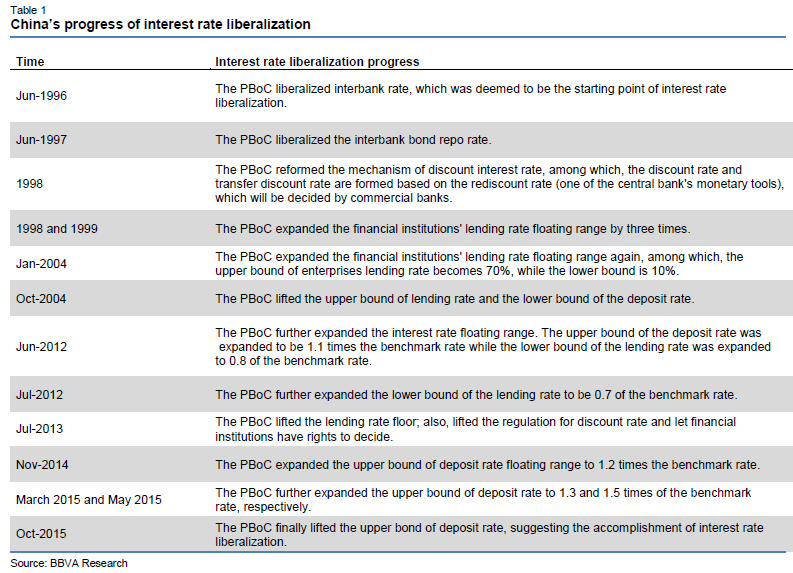

It takes more than two decades to complete interest rate liberalization in China. After China embarked on its journey of “Reform and Opening-up”, a modern banking system was established in parallel with a monetary policy framework. Originally, the monetary policy framework was characterized by strictly administrative lending and deposit rates at all tenors. At that time, the central bank (PBoC) indeed provided two yield curves of lending and deposit rates for commercial banks to charge their clients. (Table 1)

Now as the authorities have fully liberalized lending and deposit rates, the entire interest rate system, ranging from lending and deposit rates for bank clients to the previously liberalized money market and bond market rates, are fully determined on market basis and no longer subject to the central bank’s regulations.As time passed by, the authorities have gradually liberalized interest rates in money and bond markets as well as gave more flexibility to banks in determining their lending and deposits rates offered to clients. For example, banks were allowed to offer their clients a deposit rate up to 10% higher than the central bank’s benchmark deposit rate. Under such circumstances, the central bank conducted monetary policy by adjusting not only the level of benchmark interest rates but also the permissible ranges of rates. (Table 1)interest rate liberalization poses challenges to monetary policy conduct

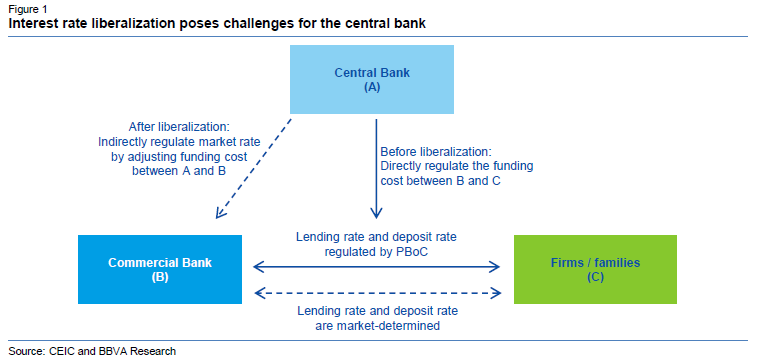

The interest rate liberalization brings about new challenges to China’s monetary policy conduct, as price policy tools, namely adjustments of lending and deposit rates, are set to lose their effectiveness. Prior to the full liberalization of interest rates, the PBoC was able to directly control funding costs of bank borrowers and saving returns of depositors by adjusting benchmark interest rates. But now the pricing power is in the hands of banks. (Figure 1) Although the PBoC renamed benchmark interest rates as “reference rates” and anticipate them continuously to guide public expectations, their real influence on banks’ setting their own lending and deposit rates remains unknown.

The PBoC still has its quantitative tools, mainly the Required Reserve Ratio (RRR) after the interest rate liberalization. However, we believe that a set of price policy tools is indispensable to a monetary policy framework based on an increasingly complex and interconnected financial system like China. The existing literature also shows that the monetary policy framework in most developed countries and many middle-income countries has moved from targeting monetary aggregates to interest rates since 1980s. That said, quantitative policy tools can perform as necessary supplements to price tools while not supplanting them.

It is noted that the new price tool should not directly link to banks’ lending and deposit rates offered to their clients. Instead, it should link to banks’ funding costs in money market or through other channels. As such, the central bank can indirectly affect banks’ behaviours by adjusting the new interest rate target. Moreover, the new policy target should be an interest rate at a short tenor. The authorities should also leave the pricing of interest rates at longer tenors to the market so as to form a yield curve on market basis.

Interest rate “corridor system” is likely to be future monetary policy framework

Theoretically, the new monetary policy framework can be chosen between a FED fund rate system (adopted by the US) and an interest rate corridor system (adopted by many countries including Euro Zone, UK, Canada, Japan, Australia, New Zealand, etc.). We believe that the corridor system is more suitable for China as the country’s financial system is dominated by commercial banks while its bond market has not been well developed. Compared with the FED fund rate system, a corridor system is more flexible which only requires the policy rate to be set within a “corridor” instead of at a “point”; moreover, a corridor system requires less open market operations (OMO) by the central bank.

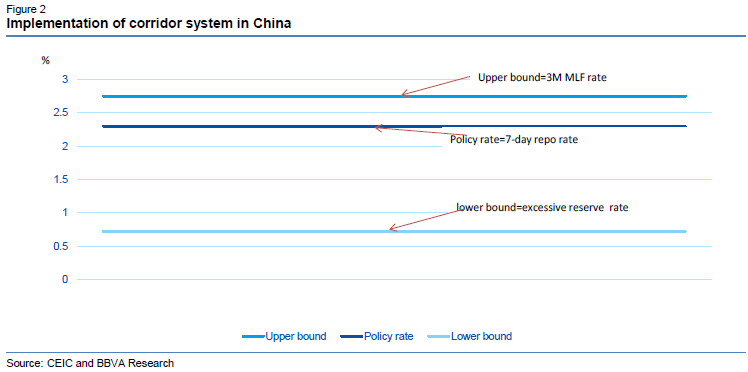

The basic principle of corridor system is as follows: the central bank provides a lending facility tool (which is the upper bound of the “corridor”) and a deposit facility tool (which is the lower bound of the “corridor”) to form an interest rate “corridor”, while the central bank’s interest rate target is somewhere within the “corridor”. Under this system, the central bank can adjust the upper and lower bounds of the “corridor” in order to guide the target interest rate on top of conducting open market operation (OMO). Theoretically, it is not necessary to make the upper and lower bound symmetric, but international experience indicates that a symmetric corridor could be better at the beginning of the system operation.

According to the international experience and previous studies, the interest rate corridor system has a number of characteristics: (i) it can reduce interest rate volatility by better guiding market expectations; (ii) it can minimize the liquidity demand for cash hoarding and reduce the frequency, magnitude, and costs of the central bank's open market operations (OMO); (iii) the optimal width of an interest rate corridor is a function of interest rate volatility, the policy adjustment cost, as well as the frequency and size of external shocks. (Niu, Zhang, Zhang, Song and Ma, 2015).[1]

In practice, when the policy target rate rises above the upper bound of the corridor, the central bank can inject liquidity to the banking sector through the lending facility to lower the target rate. By the same token, the central bank can use the deposit facility to set a floor for the policy target rate.

How to establish an interest rate “corridor system” in China

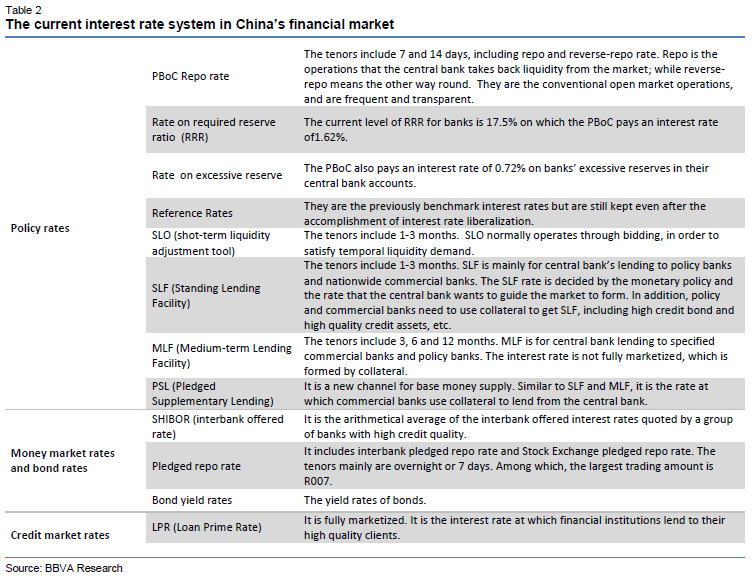

It might take years to establish an interest rate corridor system, key to which is to select some interest rates as the policy target and the bounds of the corridor. Fortunately, the PBoC has implemented a number of unconventional monetary policy tools over the past couple of years, which gave rise to a variety of interest rates in financial system. In addition to spurring domestic economy, we believe that the central bank, by unveiling these new invented tools, made preparations for the prospective transition of monetary policy framework. (Table 2)

Indeed, the PBoC has explicitly indicated to use Standing Lending Facility (SLF) rate and Medium-term Lending Facility (MLF) as the upper bound of the corridor, but has not specified which would be the lower bound rate and the policy rate. However, it seems that the excessive reserve interest rate is a natural candidate for the lower bound rate. (Now the PBoC is paying 0.72% for banks’ excessive reserves in their central bank accounts.) Regarding the policy rate, the pledged 7-day Repo rate (which has much lower volatility than SHIBOR) was believed by the market to be a suitable target because it not only has been actively traded in the interbank market and but also tends to have much lower volatility than SHIBOR, another potential candidate for the policy rate. Should the 7-day Repo rate are adopted together with SLF, MLF and the excessive reserve rate to form the interest rate corridor, the upper and lower bounds of the corridor now stand at 2.75% (3M MLF rate) and 0.72% (excessive reserve rate) respectively while the policy rate is around 2.3% (the current 7-day Repo rate). Such a corridor is likely to be asymmetric at the current stage. (Figure 2)

The establishment of a corridor system is likely to follow below steps:First, the PBoC could construct a de facto interest rate corridor around an implicit policy rate while not announce this implicit policy rate; Second, the PBoC is to gradually narrow down the range of this de facto interest rate corridor.

During the first two steps, the market could gradually form expectations that some short-term interest rate will become the policy target rate. Consequentially, banks may start to price their products based on this potential policy rate. The change of this policy rate will also affect banks’ decisions to set their lending and deposit rate at the longer tenors. Moreover, more financial derivatives will also be developed with reference to this policy rate.

Third, after the above mechanism takes shape, the authorities can announce the lift-off of “benchmark lending and deposit rates” (reference rates now) and officially introduce the new interest rate corridor as their monetary policy framework, in which the authorities can continue to refer to some money aggregate (such as M2) as another intermediate target for medium-and-long term. With the explicit interest rate corridor in place, the authorities can align their short-term policy rate with their desired level through open market operation (OMO).

A couple of challenges could feature the implementation of the corridor system: first, in order to anchor market expectations, the central bank needs to build up the credibility of the new policy regime as soon as possible; second, the authorities needs to pay heed to and take macro-prudential measures to mitigate the potential moral hazard problem associated with the corridor system; for instance, commercial banks could become increasingly reliant on the central bank facilities to meet their liquidity needs.

More monetary easing measures are in the pipeline

As headwinds to China’s growth grow stronger, we expect the authorities to deploy more easing measures on the monetary front in a bid to stimulate domestic demand in 2016. However, in the post period of interest rate liberalization, the PBoC need to develop new price tools in their policy ammunitions. It is reported that the PBoC increased their operations under the MLF to inject a large amount of liquidity in the run-up to the Chinese New Year, so as to stabilize interbank market rates. Meanwhile, the PBoC lowered MLF interest rates at 6M and 12M tenors by 15 and 25bps, to 2.85% and 3.0% respectively. In so doing, the PBoC avoided leaving investors the impression that they are substantially loosening monetary policy, which could add more pressure on stabilizing the exchange rate in the aftermath of wild movements at the beginning of this year. More importantly, the PBoC, we believe, is attempting to guide the market gradually to adapt to their nascent policy regime based on the interest rate corridor.

Admittedly, the credibility of the new policy regime could hamper the effectiveness of new policy tools. Moreover, the undergoing normalization of the US monetary policy could further narrow the interest rate differential between the US and China and then weigh on the RMB exchange rate. Under such circumstances, we envisage that quantitative policy tools will play an important role in monetary easing this year. In particular, we project that the PBoC will enact four RRR cuts (50 bps each time) in the rest of this year.

On the side of interest rates, the authorities could lower the reference lending rate twice (50 bps each time), signaling their loosening policy stance. However, investors’ attention should shift to the SLF and MLF rates since they are likely to constitute the upper bound of the prospective interest rate corridor. That being said, we expect the authorities to lower the upper bound by around 50 bps through this year to spur domestic growth. Given that the 7-day repo rate is now close to the upper bound, the decline in the MLF rate could effectively lower bank funding costs and then pass through to their borrowers.