Steve H. Hanke:The “Strong” Dollar Hits U.S. Corporate Profits

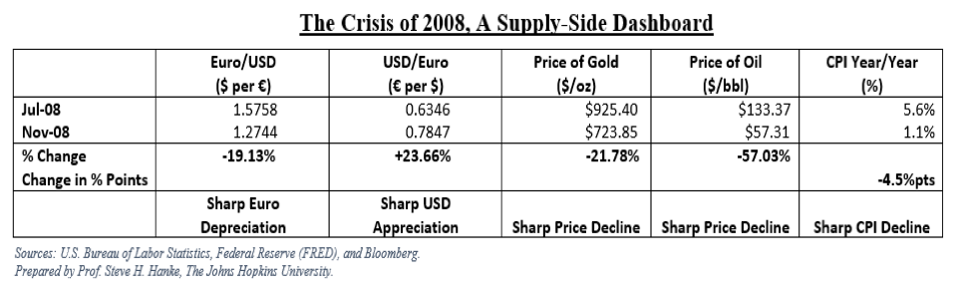

2019-10-31 IMI So, in terms of monetary policy, Mundell saw the obvious: the Fed was too tight—massively too tight. The dollar was soaring, and commodity prices were collapsing. Fed Chairman Bernanke saw none of this because exchange-rates weren’t even on his dashboard. Alas, the Fed’s massive monetary squeeze and resulting unstable dollar ushered the economy into a recession.

Well, here we are again. Today, there is a great deal of strain in the international anti-system. The dollar’s strength has ratcheted up emerging market pain. Indeed, emerging markets and commodities are under a great deal of downward pressure. And, several emerging market currencies—most notably Argentina’s peso—have collapsed, sending inflation soaring. It’s time to jettison the international anti-system and go for stability

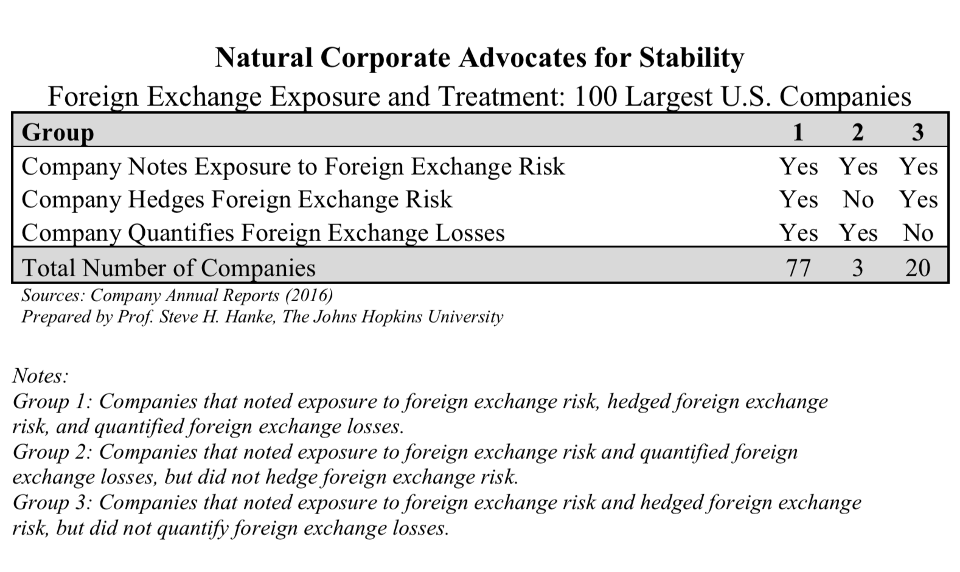

This earning season is not the only time corporations have shown concern for exchange-rate instability and its associated risks. Back in 2017, I tasked two of my assistants, Zackary Baker and Cameron Little, with what was an onerous job. They read every annual report of the 100 largest U.S. Companies to determine whether the companies noted exposure to foreign exchange risk, whether they hedged those risks, and whether they quantified their foreign exchange losses.

As the chart below indicates, 100% of the largest U.S. companies indicated an exposure to foreign exchange risks, with 80% indicating that they quantified their losses. Its obvious: U.S. corporations should provide a strong coalition to support a new system that would ensure more exchange-rate fixity and predictability.

So, in terms of monetary policy, Mundell saw the obvious: the Fed was too tight—massively too tight. The dollar was soaring, and commodity prices were collapsing. Fed Chairman Bernanke saw none of this because exchange-rates weren’t even on his dashboard. Alas, the Fed’s massive monetary squeeze and resulting unstable dollar ushered the economy into a recession.

Well, here we are again. Today, there is a great deal of strain in the international anti-system. The dollar’s strength has ratcheted up emerging market pain. Indeed, emerging markets and commodities are under a great deal of downward pressure. And, several emerging market currencies—most notably Argentina’s peso—have collapsed, sending inflation soaring. It’s time to jettison the international anti-system and go for stability

This earning season is not the only time corporations have shown concern for exchange-rate instability and its associated risks. Back in 2017, I tasked two of my assistants, Zackary Baker and Cameron Little, with what was an onerous job. They read every annual report of the 100 largest U.S. Companies to determine whether the companies noted exposure to foreign exchange risk, whether they hedged those risks, and whether they quantified their foreign exchange losses.

As the chart below indicates, 100% of the largest U.S. companies indicated an exposure to foreign exchange risks, with 80% indicating that they quantified their losses. Its obvious: U.S. corporations should provide a strong coalition to support a new system that would ensure more exchange-rate fixity and predictability.

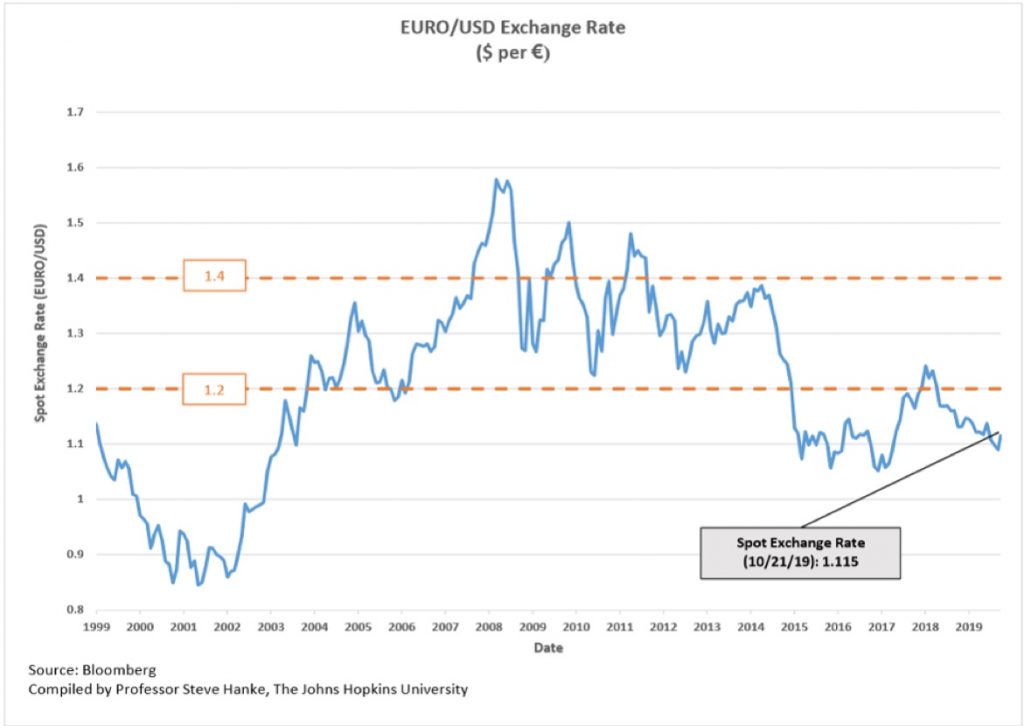

So, what has to be stabilized? The world’s two most important currencies — the dollar and the euro — should, via formal agreement, trade in a zone of stability ($1.20 – $1.40 per euro, for example). Under such an agreement, the European Central Bank (ECB) would be obliged to maintain this zone of stability by defending a weak dollar via dollar purchases. Likewise, the U.S. Treasury (UST) would be obliged to defend a weak euro by purchasing euros. Just what would have happened under such a system (counterfactually) since the introduction of the euro in 1999 is depicted in the chart below. When the euro-dollar exchange rate was less than $1.20 per euro and the euro was weak, the UST would have been purchasing euros (in the 1999 - 2003 and the 2014 – 2019 periods). When the euro-dollar exchange-rate was above $1.40 per euro and the dollar was weak, the ECB would have been purchasing dollars (in some of the 2007-2011 period).

Stability might not be everything, but everything is nothing without stability.

So, what has to be stabilized? The world’s two most important currencies — the dollar and the euro — should, via formal agreement, trade in a zone of stability ($1.20 – $1.40 per euro, for example). Under such an agreement, the European Central Bank (ECB) would be obliged to maintain this zone of stability by defending a weak dollar via dollar purchases. Likewise, the U.S. Treasury (UST) would be obliged to defend a weak euro by purchasing euros. Just what would have happened under such a system (counterfactually) since the introduction of the euro in 1999 is depicted in the chart below. When the euro-dollar exchange rate was less than $1.20 per euro and the euro was weak, the UST would have been purchasing euros (in the 1999 - 2003 and the 2014 – 2019 periods). When the euro-dollar exchange-rate was above $1.40 per euro and the dollar was weak, the ECB would have been purchasing dollars (in some of the 2007-2011 period).

Stability might not be everything, but everything is nothing without stability.