Betty Huang, Alvaro Ortiz, Tomasa Rodrigo and Le Xia:Five Facts about Outward Direct Investment

2019-04-16 IMI Fact 2: ODI to BRI countries accounted for a larger share

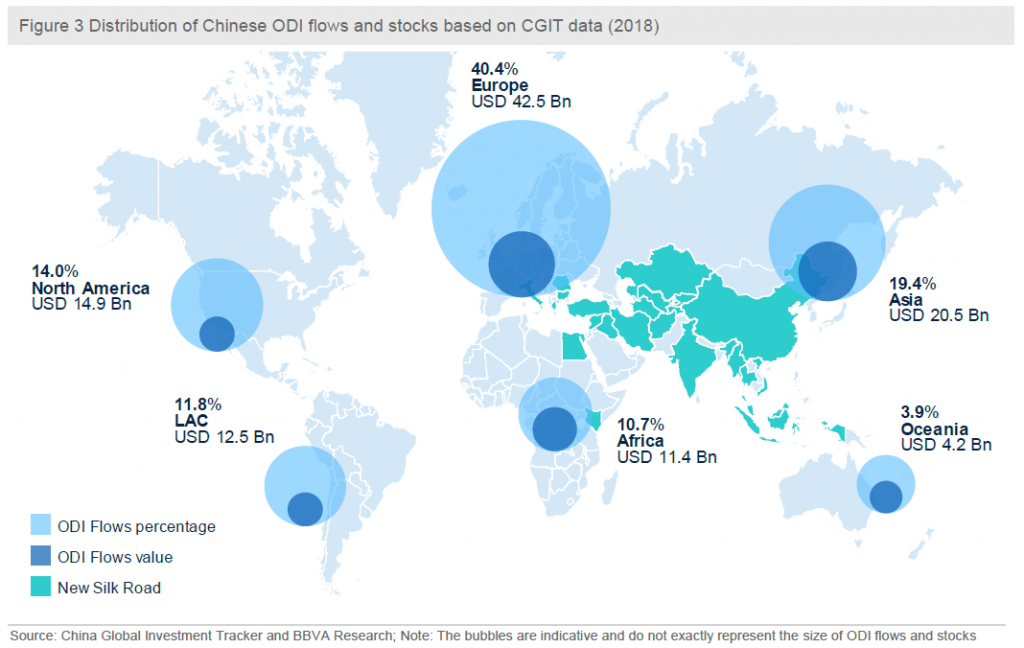

China’s official ODI data is notoriously inaccurate for reporting its destinations. In total, approximately 60% of China’s total ODI flows to Hong Kong and some tax havens in the Caribbean, through which funds are expected to be channelled to their final destinations at a later stage. Therefore, we use a more detailed database by CGTI which includes all verified investment and construction transactions worth USD 100 million or more to detect where ODI goes. The CGTI data features more than 1,300 investment deals worth more than USD 1 trillion in total. Such a deal-based database enables us to better track China's ODI flows and stocks to different destinations (Figure 3).

In terms of geographic distribution, China’s ODI flows to Europe, Asia, and North America, which remains the first largest recipient continents of China’s investment, all saw significant declines in 2018. In particular, the declines in China’s ODI to Europe and North America amount to -56.3% and -60.0% respectively. In Asia, the ODI decline is led by Japan and Singapore. The same trend is observed in Oceania. Overall, it reflects advanced countries’ increasing concerns over China’s investment.

Meanwhile, China’s ODI flows to emerging markets are still booming thanks to China’s Belt and Road Initiatives (BRI) which aims to increase China’s investment in a large number of developing countries which have traditional trade links with China. In 65 BRI countries earmarked by China’s authorities, China’s investment even increased by 8.0% in 2018. The share of investment in these BRI countries now accounts for 21.6% from 16.8% in 2016. The BRI effect is particularly pronounced in Africa, where the number of host countries of China’s ODI increased to 11 in 2018 from only 4 in 2017.

Apart from these BRI countries, the performance of Latin America also held well as the total China ODI to the region almost remained flat in 2018. In this respect, Chile ranked first with an aggregate USD 6.4 billion thanks to a big acquisition of metal mine, followed by Peru (USD 3.6 billion), Brazil (USD 1.3 billion), and Ecuador (USD 0.9 billion).

Fact 2: ODI to BRI countries accounted for a larger share

China’s official ODI data is notoriously inaccurate for reporting its destinations. In total, approximately 60% of China’s total ODI flows to Hong Kong and some tax havens in the Caribbean, through which funds are expected to be channelled to their final destinations at a later stage. Therefore, we use a more detailed database by CGTI which includes all verified investment and construction transactions worth USD 100 million or more to detect where ODI goes. The CGTI data features more than 1,300 investment deals worth more than USD 1 trillion in total. Such a deal-based database enables us to better track China's ODI flows and stocks to different destinations (Figure 3).

In terms of geographic distribution, China’s ODI flows to Europe, Asia, and North America, which remains the first largest recipient continents of China’s investment, all saw significant declines in 2018. In particular, the declines in China’s ODI to Europe and North America amount to -56.3% and -60.0% respectively. In Asia, the ODI decline is led by Japan and Singapore. The same trend is observed in Oceania. Overall, it reflects advanced countries’ increasing concerns over China’s investment.

Meanwhile, China’s ODI flows to emerging markets are still booming thanks to China’s Belt and Road Initiatives (BRI) which aims to increase China’s investment in a large number of developing countries which have traditional trade links with China. In 65 BRI countries earmarked by China’s authorities, China’s investment even increased by 8.0% in 2018. The share of investment in these BRI countries now accounts for 21.6% from 16.8% in 2016. The BRI effect is particularly pronounced in Africa, where the number of host countries of China’s ODI increased to 11 in 2018 from only 4 in 2017.

Apart from these BRI countries, the performance of Latin America also held well as the total China ODI to the region almost remained flat in 2018. In this respect, Chile ranked first with an aggregate USD 6.4 billion thanks to a big acquisition of metal mine, followed by Peru (USD 3.6 billion), Brazil (USD 1.3 billion), and Ecuador (USD 0.9 billion).

Fact 3: Energy sector continues to outpace other sectors

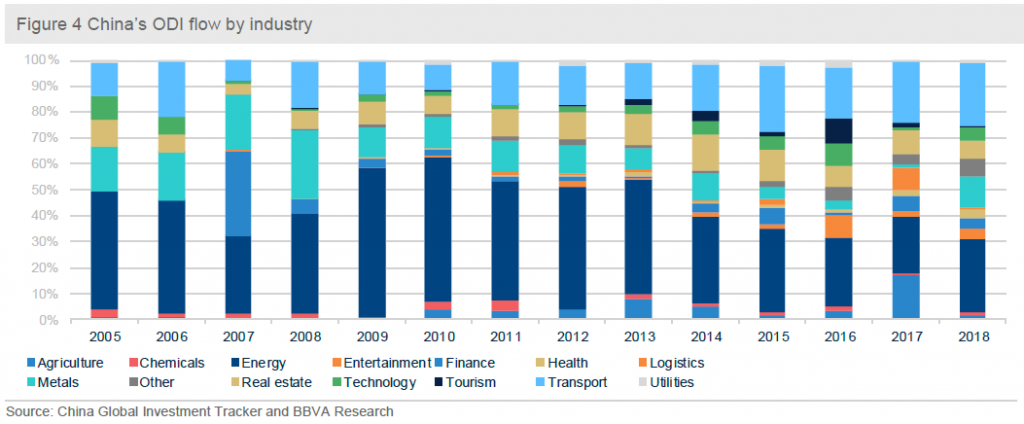

By industry, China’s ODI in the energy sector still dominated in 2018, in line with the trend during 2005-2018. Energy sector received USD 21.1 billion in investment in 2018, with Gas and Hydro seeing more activity than coal and oil. Investment in the transport sector also picked up significantly thanks to China’s Geely’s high-profile acquisition of Daimler. The metals sector received USD 18.85 billion investment last year, led by copper and steel. Health and technology sectors expanded their shares of the total received ODI. However, the once-hot fields of entertainment, real estate and tourism (hotels) registered just USD 5 billion in investment compared with USD 12.9 billion in 2017, after Beijing imposed restrictions to stem capital flight.

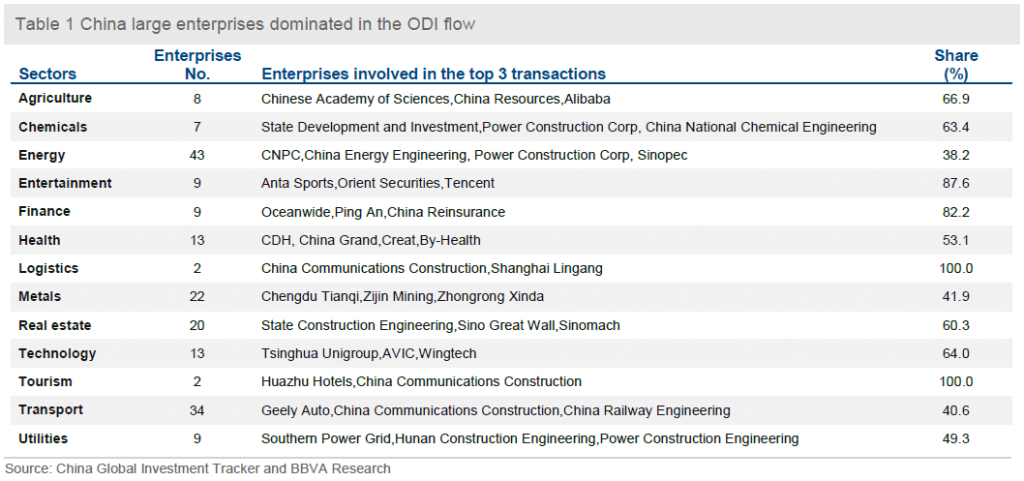

Most of the transactions are dominated by large firms. For most of them, the value of top 3 transactions e.g. Agriculture, Chemicals, real estate, technology etc. accounted for over half of that of total transactions, while sectors in energy, transport, and metals showed a more diverse investment. (Table 1)

Fact 3: Energy sector continues to outpace other sectors

By industry, China’s ODI in the energy sector still dominated in 2018, in line with the trend during 2005-2018. Energy sector received USD 21.1 billion in investment in 2018, with Gas and Hydro seeing more activity than coal and oil. Investment in the transport sector also picked up significantly thanks to China’s Geely’s high-profile acquisition of Daimler. The metals sector received USD 18.85 billion investment last year, led by copper and steel. Health and technology sectors expanded their shares of the total received ODI. However, the once-hot fields of entertainment, real estate and tourism (hotels) registered just USD 5 billion in investment compared with USD 12.9 billion in 2017, after Beijing imposed restrictions to stem capital flight.

Most of the transactions are dominated by large firms. For most of them, the value of top 3 transactions e.g. Agriculture, Chemicals, real estate, technology etc. accounted for over half of that of total transactions, while sectors in energy, transport, and metals showed a more diverse investment. (Table 1)

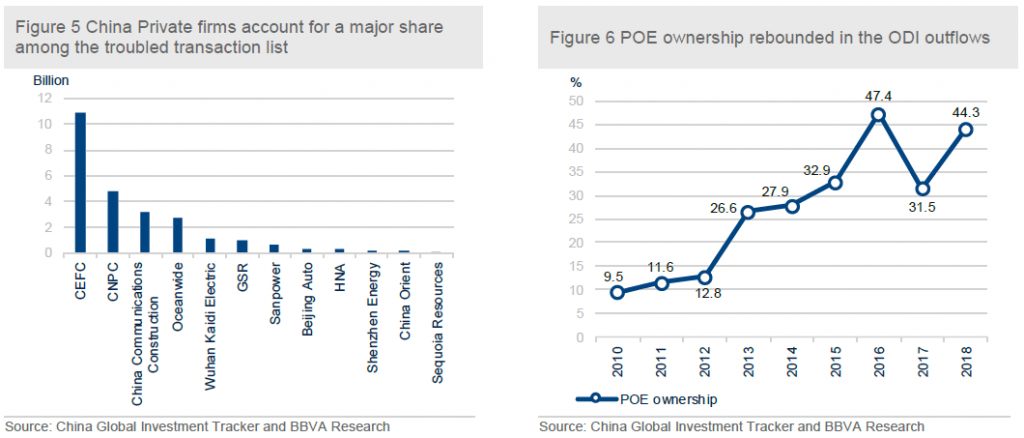

Fact 4: POEs and SOEs have different troubles

The ODI of Chinese private enterprises (POEs) was suppressed by the authorities’ clampdown on a capital flight during 2016-2017. Now Chinese POEs continued to struggle with more restricted domestic regulations which led to more troubled transactions of ODI. (Figure 5) Moreover, the tightening financing condition in China makes it increasingly difficult for those POEs to find financing sources to meet their demand for ODI. Notwithstanding the above obstacles, the absolute volume of POE overseas investment at least held up in 2018. (Figure 6)

Meanwhile, China’s state-owned enterprises (SOEs) are facing a different set of problems in making ODI. Compared to their private peers, SOEs can easily find overseas construction projects tied to the government’s favoured BRI strategy as well as concessionary financing. However, the suspicion of foreign governments made it increasingly difficult for them to pass the host countries’ screening mechanism of foreign investment.

Fact 4: POEs and SOEs have different troubles

The ODI of Chinese private enterprises (POEs) was suppressed by the authorities’ clampdown on a capital flight during 2016-2017. Now Chinese POEs continued to struggle with more restricted domestic regulations which led to more troubled transactions of ODI. (Figure 5) Moreover, the tightening financing condition in China makes it increasingly difficult for those POEs to find financing sources to meet their demand for ODI. Notwithstanding the above obstacles, the absolute volume of POE overseas investment at least held up in 2018. (Figure 6)

Meanwhile, China’s state-owned enterprises (SOEs) are facing a different set of problems in making ODI. Compared to their private peers, SOEs can easily find overseas construction projects tied to the government’s favoured BRI strategy as well as concessionary financing. However, the suspicion of foreign governments made it increasingly difficult for them to pass the host countries’ screening mechanism of foreign investment.

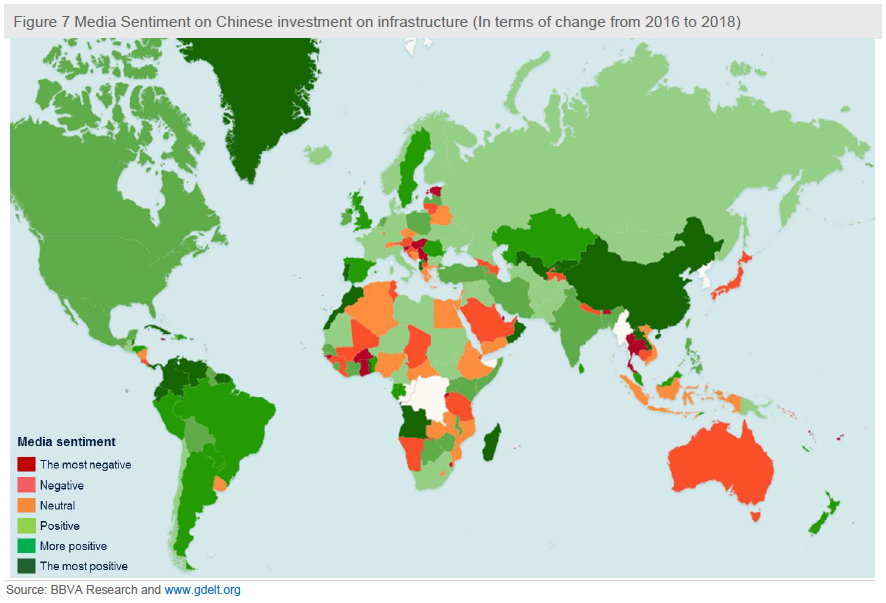

Fact 5: Other countries’ sentiment toward China’s investment is mixed

Encouragingly, many foreign countries’ views toward China’s investment have somewhat improved over the past two years despite the rise in the populism around the globe. Using Big Data and information from the media (GDELT), we measure the media coverage and sentiment on news related to the BRI initiative. Reassuringly, we find that the evolution of media sentiment of Chinese investment on infrastructure has improved generally in 2018 compared to 2016 (Figure 7). Among these regions, Latam America has the most positive sentiment toward China’s investment, while South Asia has the least-positive sentiment of the investment e.g. Bhutan, Maldives, Thailand and Indonesia, reflecting these regions’ long-term territory dispute and economic competition with China. That being said, China needs to carefully tackle these sensitive issues with its neighbours if it wants to successfully push forward the BRI around the globe.

China’s ODI is likely to bottom out in 2019

At the beginning of the report, we identified three important factors which had an adverse impact on China’s ODI, including tightened domestic regulations, increasing concerns of foreign governments and sluggish economic growth. These three factors are unlikely to improve in the near term. Capital flight continues to be a concern of China’s authorities while foreign governments’ suspicion toward China’s investment in their high-tech sector is more likely to strengthen rather than fade (Please see our recent report of China-gauging-the-impact-of-us-tech-war-on-china-an-input-output-table-analysis/). Moreover, the deceleration of China’s growth is more likely to continue in the next couple of years.

Despite the abovementioned headwinds, we still hold a conservatively optimistic view of China’s ODI over the medium term and anticipate the country’s ODI to bottom out in 2019. Compared to its share of global GDP (18.3%), China’s share of global FDI still has room to grow (4.7%). Moreover, China’s ODI will benefit substantially from the BRI strategy. In this respect, a number of newly established China-initiated institutions, including Silk Road Fund, Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), BRICS New Development Bank (NDB), China LAC Industrial Cooperation Investment Fund and the China-Latin America Infrastructure Fund, will play an increasingly important role. As such, infrastructure and commodity sectors in emerging markets will attract more Chinese capitals.

Fact 5: Other countries’ sentiment toward China’s investment is mixed

Encouragingly, many foreign countries’ views toward China’s investment have somewhat improved over the past two years despite the rise in the populism around the globe. Using Big Data and information from the media (GDELT), we measure the media coverage and sentiment on news related to the BRI initiative. Reassuringly, we find that the evolution of media sentiment of Chinese investment on infrastructure has improved generally in 2018 compared to 2016 (Figure 7). Among these regions, Latam America has the most positive sentiment toward China’s investment, while South Asia has the least-positive sentiment of the investment e.g. Bhutan, Maldives, Thailand and Indonesia, reflecting these regions’ long-term territory dispute and economic competition with China. That being said, China needs to carefully tackle these sensitive issues with its neighbours if it wants to successfully push forward the BRI around the globe.

China’s ODI is likely to bottom out in 2019

At the beginning of the report, we identified three important factors which had an adverse impact on China’s ODI, including tightened domestic regulations, increasing concerns of foreign governments and sluggish economic growth. These three factors are unlikely to improve in the near term. Capital flight continues to be a concern of China’s authorities while foreign governments’ suspicion toward China’s investment in their high-tech sector is more likely to strengthen rather than fade (Please see our recent report of China-gauging-the-impact-of-us-tech-war-on-china-an-input-output-table-analysis/). Moreover, the deceleration of China’s growth is more likely to continue in the next couple of years.

Despite the abovementioned headwinds, we still hold a conservatively optimistic view of China’s ODI over the medium term and anticipate the country’s ODI to bottom out in 2019. Compared to its share of global GDP (18.3%), China’s share of global FDI still has room to grow (4.7%). Moreover, China’s ODI will benefit substantially from the BRI strategy. In this respect, a number of newly established China-initiated institutions, including Silk Road Fund, Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), BRICS New Development Bank (NDB), China LAC Industrial Cooperation Investment Fund and the China-Latin America Infrastructure Fund, will play an increasingly important role. As such, infrastructure and commodity sectors in emerging markets will attract more Chinese capitals.