Dong Jinyue and Xia Le: Peering into China’s Local Government Debt——Rising Risks Call for Prompt Actions

2018-11-19 IMI The evolution of China’s local government debt

The history of local government financing vehicles can date back to late 1990s. Under China’s judicial system, local governments are subordinate agencies of the central government and have long been forbidden to borrow from financial institutions or capital market directly. However, some local governments in late 1990s started to establish some special-purposed vehicles to obtain financing for their local infrastructure projects. These special-purposed vehicles were the first generation of local government financing vehicles (LGFVs). Generally, the size of local government debt was limited in 1990s.

The fast accumulation of local government debt started with China’s famous 4-trillion stimulus package, which were unveiled in response to the 2008-2009 Global Financial Crisis (GFC). To finance the infrastructure projects contained in the stimulus package, local governments, with the central government’s acquiescence, established numerous LGFVs to borrow funds from financial institutions and capital market.

Soon the authorities started to realize the risks associated with the fast rise in local government debt and attempted to curb the borrowing of local governments. In June 2011, the State Council promulgated new measures on regulating LGFVs, aiming at clearing off the illegal LGFVs and prohibiting local governments’ pledges on LGFVs. It is noted that at that moment the central government refused to acknowledge that local governments have any payment obligations for the LGFVs borrowing. Instead, the central government urged local governments to withdraw their explicit or implicit financial supports for LGFVs.

However, the implemented tightening measures failed to stop further accumulation of local government debt. To meet the stringent growth target, local governments had no other way to boost local economies but to borrow more to invest in infrastructure projects. Consequentially, the growing size of local government debt poses increasing risks to the financial stability.

In 2013, the authorities stepped up their tightening efforts to urge the local governments to build up the early warning mechanism for their debt. More importantly, in October 2014, China’s State Council promulgated a set of new rules to regulate local government debt (called as No. 43 Document). Chief among them is the central government’s “no-bailout” principle towards debt obligations of local governments.

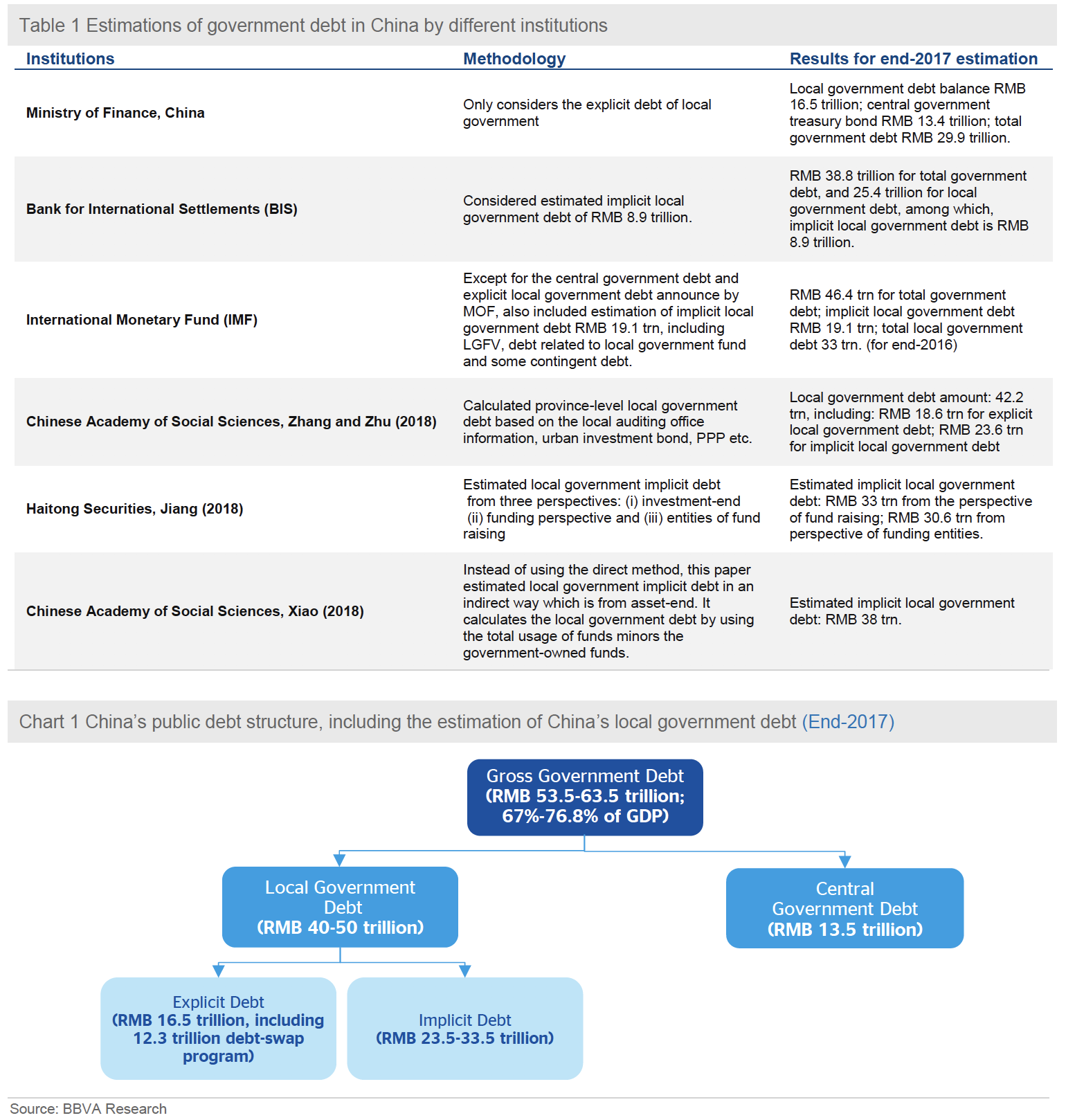

At the same time, the central government had to change their previous stance and acknowledged that part of LGFV debt is indeed local government debt. The central government set out to help local government control the debt size and alleviate associated risks. In 2015, the central government announced a debt-swap program, which aimed to swaps local government debt of 12.3 trillion for equivalent amount of municipal bonds by end-2018. Through this program, local governments not only can roll-over part of their debt but also lower their interest rate costs. Now the debt-swap program is closed to meet its pre-set target.

However, it seems difficult for local governments to wean off their addiction of debt-borrowing. After the promulgation of 2014’s No.43 document, local governments started to embrace the projects of public-private partnerships (PPP) in infrastructure investment. Unfortunately, the majority of Chinese PPP projects are in essence upgraded version of LGFVs as the final stakeholders and risk-takers are still local governments. In these PPP projects, the private partners are just being invited to participate so that the projects are qualified to borrow from financial institutions.

Vulnerabilities and risks associated with local government debt

Ballooning local government debt is subject to a number of vulnerabilities.

The majority of local government debt, either in the form of LGFV borrowing or PPP, are invested in long-term infrastructure projects. It led to a maturity mismatch for the liability and asset sides of the LGFV or the project company of PPP. Moreover, the viability of many infrastructure projects is questionable in terms of their capacity to generate enough cash flow to pay back interest and principals.

As such, local government debt is subject to grave roll-over risks. The change of credit condition could have a significant impact on the sustainability local government debt. As domestic credit condition has become tighter due to the authorities’ efforts to control financial leverage, the pressure on local government debt is mounting.

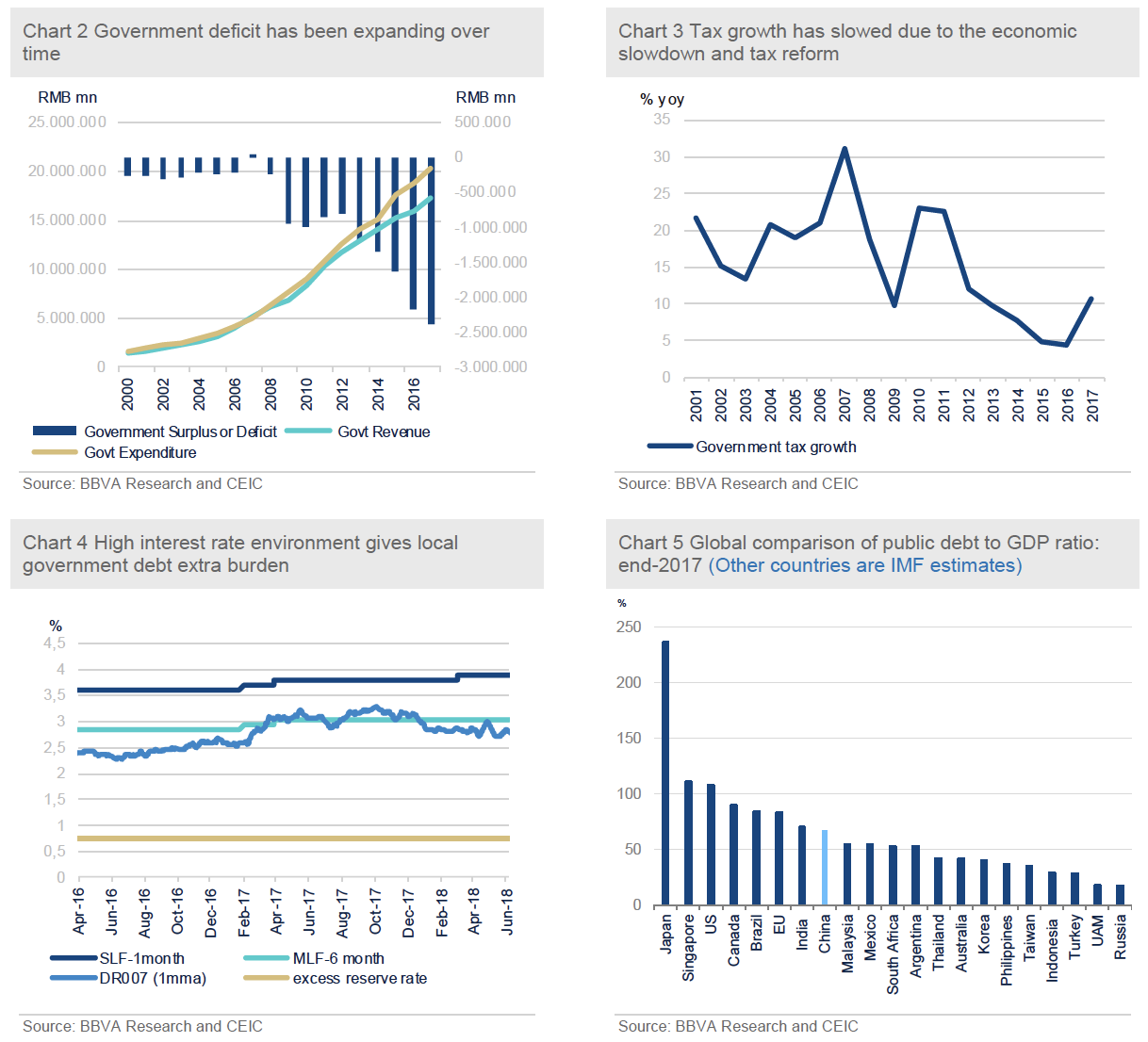

Meanwhile, the financial fundamentals of local governments have become worse as well. As a result of growth slowdown and the tax reform of replacing business taxes with value-added taxes, the growth of tax revenues has slowed over the past few years. (Chart 2 and 3) In addition, land sale revenues, which constitute a lion’s share of local government fiscal revenues, have become increasingly unstable in recent years due to the authorities’ stepped-up efforts to clamp down housing bubbles. Moreover, as the FED interest rate normalization proceeds, high interest rate environment in emerging market may also add extra burden for local government repayment.

(Chart 4) All in all, the deteriorating financial situation of local governments means that their debt-servicing capacity has weakened.

The evolution of China’s local government debt

The history of local government financing vehicles can date back to late 1990s. Under China’s judicial system, local governments are subordinate agencies of the central government and have long been forbidden to borrow from financial institutions or capital market directly. However, some local governments in late 1990s started to establish some special-purposed vehicles to obtain financing for their local infrastructure projects. These special-purposed vehicles were the first generation of local government financing vehicles (LGFVs). Generally, the size of local government debt was limited in 1990s.

The fast accumulation of local government debt started with China’s famous 4-trillion stimulus package, which were unveiled in response to the 2008-2009 Global Financial Crisis (GFC). To finance the infrastructure projects contained in the stimulus package, local governments, with the central government’s acquiescence, established numerous LGFVs to borrow funds from financial institutions and capital market.

Soon the authorities started to realize the risks associated with the fast rise in local government debt and attempted to curb the borrowing of local governments. In June 2011, the State Council promulgated new measures on regulating LGFVs, aiming at clearing off the illegal LGFVs and prohibiting local governments’ pledges on LGFVs. It is noted that at that moment the central government refused to acknowledge that local governments have any payment obligations for the LGFVs borrowing. Instead, the central government urged local governments to withdraw their explicit or implicit financial supports for LGFVs.

However, the implemented tightening measures failed to stop further accumulation of local government debt. To meet the stringent growth target, local governments had no other way to boost local economies but to borrow more to invest in infrastructure projects. Consequentially, the growing size of local government debt poses increasing risks to the financial stability.

In 2013, the authorities stepped up their tightening efforts to urge the local governments to build up the early warning mechanism for their debt. More importantly, in October 2014, China’s State Council promulgated a set of new rules to regulate local government debt (called as No. 43 Document). Chief among them is the central government’s “no-bailout” principle towards debt obligations of local governments.

At the same time, the central government had to change their previous stance and acknowledged that part of LGFV debt is indeed local government debt. The central government set out to help local government control the debt size and alleviate associated risks. In 2015, the central government announced a debt-swap program, which aimed to swaps local government debt of 12.3 trillion for equivalent amount of municipal bonds by end-2018. Through this program, local governments not only can roll-over part of their debt but also lower their interest rate costs. Now the debt-swap program is closed to meet its pre-set target.

However, it seems difficult for local governments to wean off their addiction of debt-borrowing. After the promulgation of 2014’s No.43 document, local governments started to embrace the projects of public-private partnerships (PPP) in infrastructure investment. Unfortunately, the majority of Chinese PPP projects are in essence upgraded version of LGFVs as the final stakeholders and risk-takers are still local governments. In these PPP projects, the private partners are just being invited to participate so that the projects are qualified to borrow from financial institutions.

Vulnerabilities and risks associated with local government debt

Ballooning local government debt is subject to a number of vulnerabilities.

The majority of local government debt, either in the form of LGFV borrowing or PPP, are invested in long-term infrastructure projects. It led to a maturity mismatch for the liability and asset sides of the LGFV or the project company of PPP. Moreover, the viability of many infrastructure projects is questionable in terms of their capacity to generate enough cash flow to pay back interest and principals.

As such, local government debt is subject to grave roll-over risks. The change of credit condition could have a significant impact on the sustainability local government debt. As domestic credit condition has become tighter due to the authorities’ efforts to control financial leverage, the pressure on local government debt is mounting.

Meanwhile, the financial fundamentals of local governments have become worse as well. As a result of growth slowdown and the tax reform of replacing business taxes with value-added taxes, the growth of tax revenues has slowed over the past few years. (Chart 2 and 3) In addition, land sale revenues, which constitute a lion’s share of local government fiscal revenues, have become increasingly unstable in recent years due to the authorities’ stepped-up efforts to clamp down housing bubbles. Moreover, as the FED interest rate normalization proceeds, high interest rate environment in emerging market may also add extra burden for local government repayment.

(Chart 4) All in all, the deteriorating financial situation of local governments means that their debt-servicing capacity has weakened.

The market prime concern about local government debt is its sustainability. It is true that some local governments are unable to solve their debt problem by themselves. It means that certain forms of financial support or even bail-out from the central government are imperative. Indeed, under the current administrative structure, the central government has obligations for the debt borrowed by local governments.

We believe that the central government still has enough capacity to manage the current level of public debt, including both central and local government debt. According to our estimate, China’s local government debt stands at 50%-62.5% of GDP. Together with existing central government debt, the general public debt in China could reach 67.0%-76.8% of GDP. Such a level is higher than those of many developing economies but lower than those of advanced countries. (Chart 5) Fortunately, the public debt in China is mainly financed by domestic funds and accordingly denominated in the Chinese currency. As long as China maintains a high saving rate and fulfil its potential growth (5-6% as we estimated), it should not be a problem for the central government to service public debt of the current level.

However, the largest challenge to China’s debt sustainability is whether the authorities can find an effective way to prevent further rise in local government debt. In the past several years, the augmented fiscal deficit (including both the central and local governments’ deficits) grew at a pace of around 10% annually. If China’s authorities cannot effectively curtail further piling-up of local government debt, the country’s total public debt could exceed the international warning line of 90% in the next couple of years. By then the indebtedness is likely to have a significantly negative impact on growth and even financial stability. That being said, the Chinese authorities need to take prompt actions to curtail the fast accumulation of local government debt before it climbs to an unmanageable level.

More needs to be done to defuse the risks

We believe that the main focus of addressing local government debt should be to control its further increase. We summarize some measures which have been implemented or likely to be implemented to address this issue below.

(i) Downplay the importance of GDP growth for the local governments. As explained previously, the root cause for debt accumulation at the local government level is their faced persistent pressure of meeting growth target. Therefore, it is essential to change the incentive mechanism of local governments so that they have less appetite for further borrowing. In last year’s concluded 19th Party’s Congress, the authorities have pledged to downplay the growth target in future. However, in practice it highly depends on to what extent the central government could tolerate growth slowdown.

(ii) Include the local government future borrowings into the fiscal budget through legal process. Starting from 2015, China implemented a new Budget Law, stipulating that all the new borrowings of local governments must be included in their budget, regulated by local People’s Congress. Although this is an important progress it isn’t powerful enough to prevent further accumulation of local government debt as we analysed. Above all, this move points to the right direction. Looking ahead, the central government is likely to instruct local governments to disclose more financial information, in particular relating to LGFVs or local government controlled state-owned enterprises (SOEs), in their fiscal budget so that local People’s Congress can better monitor local governments’ borrowing behaviours.

(iii) Enhance the central government’s supervision of local government debt. Indeed, the central government has beefed up their efforts in this respect. For example, since November 2017, Ministry of Finance has overhauled the approving system of PPP and rejected more PPP applications of local government debt. Till April 2018, 1,695 PPP projects with the total amount of RMB 1.8 trillion have been cancelled. More importantly, the supervision of the central government should be more comprehensive and forward-looking. It should be able to promptly identify the new forms of local government borrowing and stop them before they propagate to a large scale.

(iv) Clarify local governments’ obligation for LGFVs. Not all the LGFV borrowing should be included as local government debt. The central government needs to draw a clear line between the debt to be repaid by local governments and that to be repaid by projects themselves. On the top of it, the central government should allow individual default of the self-supported LGFVs so as to strengthen local government market discipline and avoid moral hazard problem.

(v) Expand the debt swap program. The purpose of the debt swap program is to make the maturity of LGFV borrowing better match their projects on the asset side. In addition, it helps to reduce the cost of local government borrowing. The existing debt swap program will end by this year. It is necessary to expand this program to include more newly acknowledged local government debt.

The market prime concern about local government debt is its sustainability. It is true that some local governments are unable to solve their debt problem by themselves. It means that certain forms of financial support or even bail-out from the central government are imperative. Indeed, under the current administrative structure, the central government has obligations for the debt borrowed by local governments.

We believe that the central government still has enough capacity to manage the current level of public debt, including both central and local government debt. According to our estimate, China’s local government debt stands at 50%-62.5% of GDP. Together with existing central government debt, the general public debt in China could reach 67.0%-76.8% of GDP. Such a level is higher than those of many developing economies but lower than those of advanced countries. (Chart 5) Fortunately, the public debt in China is mainly financed by domestic funds and accordingly denominated in the Chinese currency. As long as China maintains a high saving rate and fulfil its potential growth (5-6% as we estimated), it should not be a problem for the central government to service public debt of the current level.

However, the largest challenge to China’s debt sustainability is whether the authorities can find an effective way to prevent further rise in local government debt. In the past several years, the augmented fiscal deficit (including both the central and local governments’ deficits) grew at a pace of around 10% annually. If China’s authorities cannot effectively curtail further piling-up of local government debt, the country’s total public debt could exceed the international warning line of 90% in the next couple of years. By then the indebtedness is likely to have a significantly negative impact on growth and even financial stability. That being said, the Chinese authorities need to take prompt actions to curtail the fast accumulation of local government debt before it climbs to an unmanageable level.

More needs to be done to defuse the risks

We believe that the main focus of addressing local government debt should be to control its further increase. We summarize some measures which have been implemented or likely to be implemented to address this issue below.

(i) Downplay the importance of GDP growth for the local governments. As explained previously, the root cause for debt accumulation at the local government level is their faced persistent pressure of meeting growth target. Therefore, it is essential to change the incentive mechanism of local governments so that they have less appetite for further borrowing. In last year’s concluded 19th Party’s Congress, the authorities have pledged to downplay the growth target in future. However, in practice it highly depends on to what extent the central government could tolerate growth slowdown.

(ii) Include the local government future borrowings into the fiscal budget through legal process. Starting from 2015, China implemented a new Budget Law, stipulating that all the new borrowings of local governments must be included in their budget, regulated by local People’s Congress. Although this is an important progress it isn’t powerful enough to prevent further accumulation of local government debt as we analysed. Above all, this move points to the right direction. Looking ahead, the central government is likely to instruct local governments to disclose more financial information, in particular relating to LGFVs or local government controlled state-owned enterprises (SOEs), in their fiscal budget so that local People’s Congress can better monitor local governments’ borrowing behaviours.

(iii) Enhance the central government’s supervision of local government debt. Indeed, the central government has beefed up their efforts in this respect. For example, since November 2017, Ministry of Finance has overhauled the approving system of PPP and rejected more PPP applications of local government debt. Till April 2018, 1,695 PPP projects with the total amount of RMB 1.8 trillion have been cancelled. More importantly, the supervision of the central government should be more comprehensive and forward-looking. It should be able to promptly identify the new forms of local government borrowing and stop them before they propagate to a large scale.

(iv) Clarify local governments’ obligation for LGFVs. Not all the LGFV borrowing should be included as local government debt. The central government needs to draw a clear line between the debt to be repaid by local governments and that to be repaid by projects themselves. On the top of it, the central government should allow individual default of the self-supported LGFVs so as to strengthen local government market discipline and avoid moral hazard problem.

(v) Expand the debt swap program. The purpose of the debt swap program is to make the maturity of LGFV borrowing better match their projects on the asset side. In addition, it helps to reduce the cost of local government borrowing. The existing debt swap program will end by this year. It is necessary to expand this program to include more newly acknowledged local government debt.