Betty Huang and Xia Le: Not Time to Say Goodbye to HKD Peg

2018-05-14 IMI

What is Hong Kong’s linked exchange rate regime?

To better understand the Hong Kong’s linked exchange rate regime, we need to revisit the “impossible trinity”, an axiom in international economics which states that it is unmanageable for an economy to simultaneously pursue: (1) a fixed exchange rate; (2) free capital flows; and (3) an independent monetary policy.

Hong Kong has a fixed exchange rate and free capital controls, but no independent monetary policy, relying instead on the interest rates determined by the Federal Reserve of the United States (US Fed). Hong Kong’s linked exchange rate regime is also technically known as a “currency board”.

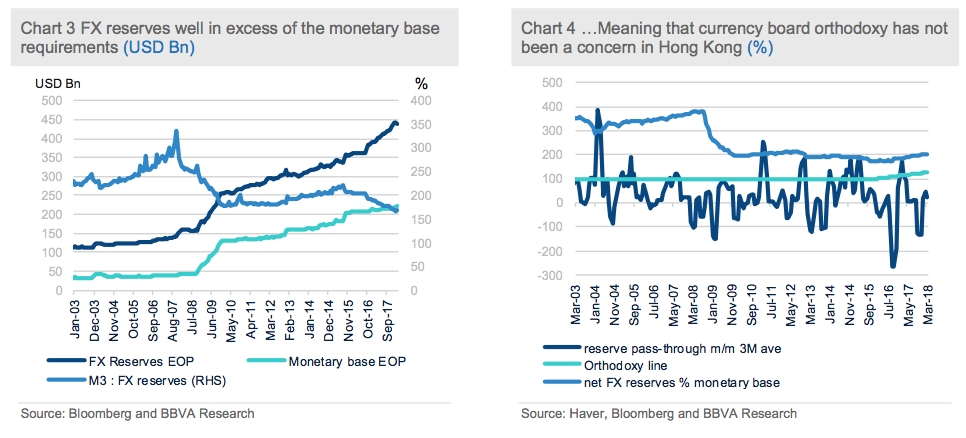

In Hong Kong, monetary policy to be rule bound and automatic, the currency board must have no discretionary monetary powers or engage in the fiduciary issue of money but to maintain the exchange rate within a narrow band currently fixed at 7.75-7.85 HKD/USD. According to the Basic Law, the “Hong Kong currency must be 100% backed by a reserve fund”. In other words, FX reserves must be enough to cover 100% or more of total monetary liabilities, which in Hong Kong are comprised by certificates of indebtedness, government-issued currency in circulation and the balance of the clearing accounts of banks kept with the HKMA. (Chart 3)

A lethal threat to a credible currency board system is that FX reserves might be used for other purposes which could lead to serious liquidity problem during the period of crisis time. The quickest way is to look at the relationship between “net foreign reserves” and the “reserve pass through” (Hanke, 2008)[1]. In an orthodox currency board, net foreign reserves should be close to or above 100% of the monetary base. In addition, the “reserve pass through”, defined as the change in monetary base divided by the change in net foreign reserves, should also be close to 100%, or at least fall within a range of 0-100%.

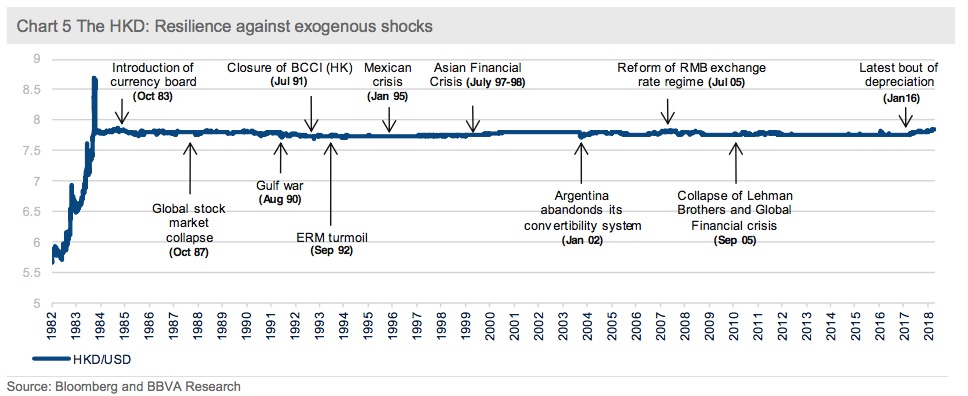

As we’ve already discussed, Hong Kong’s net FX reserves as a percentage of the monetary base linger comfortably above the 100% mark. Moreover, the reserve pass-through has, for the most part, stayed within the 0-100% band, meaning the HKMA engages only in ordinary sterilization (Chart 4). In other words, the HKMA does not hold FX assets for reasons other than to safeguard the stability of its exchange rate, leaving the entirety of its FX reserves available to defend the currency against a potential speculative attack.

What is Hong Kong’s linked exchange rate regime?

To better understand the Hong Kong’s linked exchange rate regime, we need to revisit the “impossible trinity”, an axiom in international economics which states that it is unmanageable for an economy to simultaneously pursue: (1) a fixed exchange rate; (2) free capital flows; and (3) an independent monetary policy.

Hong Kong has a fixed exchange rate and free capital controls, but no independent monetary policy, relying instead on the interest rates determined by the Federal Reserve of the United States (US Fed). Hong Kong’s linked exchange rate regime is also technically known as a “currency board”.

In Hong Kong, monetary policy to be rule bound and automatic, the currency board must have no discretionary monetary powers or engage in the fiduciary issue of money but to maintain the exchange rate within a narrow band currently fixed at 7.75-7.85 HKD/USD. According to the Basic Law, the “Hong Kong currency must be 100% backed by a reserve fund”. In other words, FX reserves must be enough to cover 100% or more of total monetary liabilities, which in Hong Kong are comprised by certificates of indebtedness, government-issued currency in circulation and the balance of the clearing accounts of banks kept with the HKMA. (Chart 3)

A lethal threat to a credible currency board system is that FX reserves might be used for other purposes which could lead to serious liquidity problem during the period of crisis time. The quickest way is to look at the relationship between “net foreign reserves” and the “reserve pass through” (Hanke, 2008)[1]. In an orthodox currency board, net foreign reserves should be close to or above 100% of the monetary base. In addition, the “reserve pass through”, defined as the change in monetary base divided by the change in net foreign reserves, should also be close to 100%, or at least fall within a range of 0-100%.

As we’ve already discussed, Hong Kong’s net FX reserves as a percentage of the monetary base linger comfortably above the 100% mark. Moreover, the reserve pass-through has, for the most part, stayed within the 0-100% band, meaning the HKMA engages only in ordinary sterilization (Chart 4). In other words, the HKMA does not hold FX assets for reasons other than to safeguard the stability of its exchange rate, leaving the entirety of its FX reserves available to defend the currency against a potential speculative attack.

Strong political will to defend the exchange rate

The political will to defend the linked exchange rate system is strong. Indeed, re-pegging the value of the HKD at the moment of currency weakness could be disastrous, as it would dampen the credibility of the monetary policy framework and trigger large-scale capital outflows. In history, the exchange rate has proven incredibly resilient to exogenous shocks in the past (Chart 5). This has boosted the authorities’ confidence in the system’s ability to undertake the necessary balance-of-payment adjustments to avert a crisis.

Strong political will to defend the exchange rate

The political will to defend the linked exchange rate system is strong. Indeed, re-pegging the value of the HKD at the moment of currency weakness could be disastrous, as it would dampen the credibility of the monetary policy framework and trigger large-scale capital outflows. In history, the exchange rate has proven incredibly resilient to exogenous shocks in the past (Chart 5). This has boosted the authorities’ confidence in the system’s ability to undertake the necessary balance-of-payment adjustments to avert a crisis.

The authorities’ quiet confidence may be well justified. For example, during the Asian Financial crisis, there was significant pressure from speculators who believed a devaluation of the HKD was inevitable. The concern at the time was that a strengthening dollar would hurt Hong Kong’s economy, which was experiencing outflows stemming from its exposure to volatile Asian markets. The HKMA’s intervention was both vigorous and merciless, driving up the 3M Hibor to almost 20% and leading to a -25% fall in the Hang Seng Index. It was also effective in driving out the short-sellers.

In 2011, US based hedge fund manager Bill Ackerman lodged a speculative attack that incoming Chief Executive CY Leung would devalue the HKD in order to curb hot money inflows from the mainland, which were fueling a property bubble in the region, thereby worsening social tensions. However, much to Ackerman’s dismay, CY Leung pledged to keep the HKD’s linked exchange rate mechanism untouched. Money was lost.

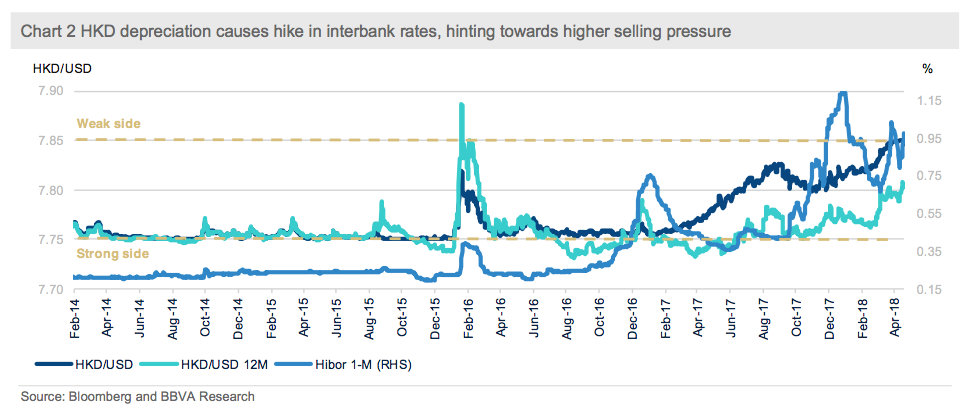

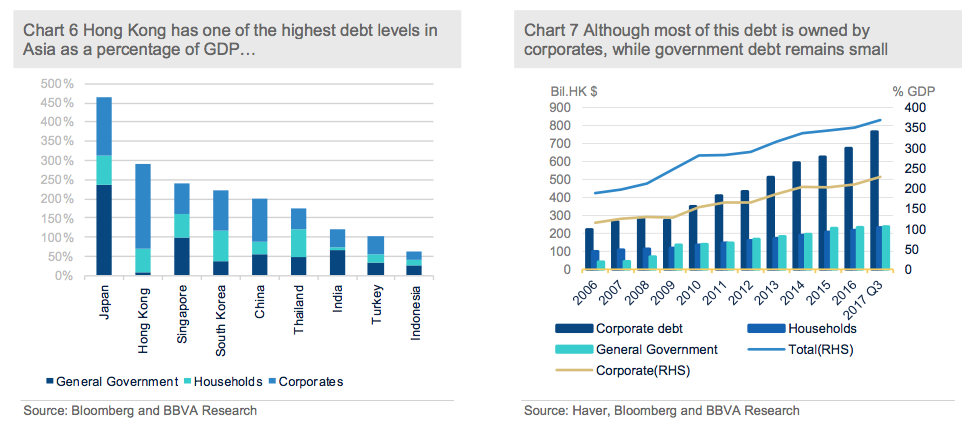

Stable HKD and higher interest rates pose risks to local economy

Admittedly, it is not hard for the HKMA to keep the HKD below the 7.85 level, but the authorities might pay a cost of a fast hike in interbank interest rate. Despite Hong Kong having maintained a very prudent fiscal policy, Hong Kong credit boom has made the economy’s total debt levels are amongst the highest in Asia, second only to Japan (Chart 6). However, unlike Japan, the bulk of this indebtedness is accounted for by corporates (Chart 7). The risks in the corporate bond market are on the rise.

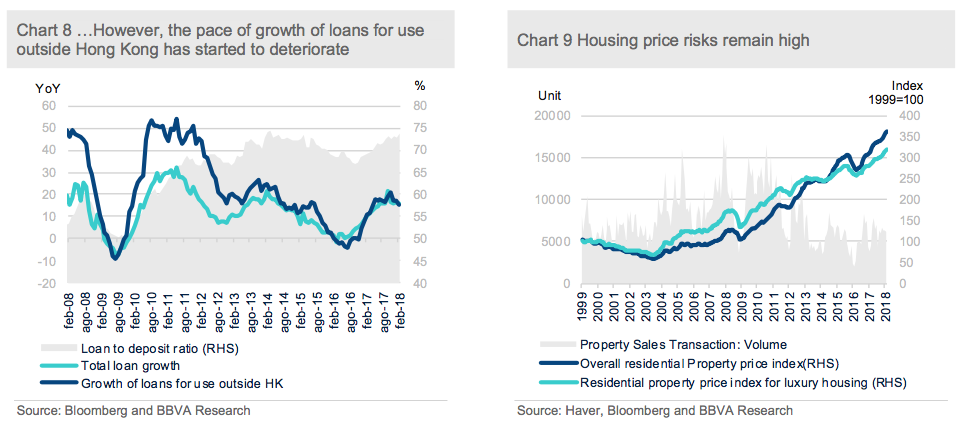

Moreover, rising interest rates and a stronger HKD will make it expensive for Chinese corporates to seek financing in Hong Kong. In fact, Hong Kong has become increasingly exposed to China’s economy. For example, loans for use outside Hong Kong have rocketed on the back of falling interest rates since 2009 (Chart 8). Banks have significantly increased their exposure to China, as we have seen that as a result of tightening mainland banking regulations, mainland companies are increasingly seeking funding in Hong Kong for their projects, especially for the real-estate sector and local government entities.

Also Hong Kong is not exempt from spill-overs from volatility in China’s financial markets. Downward pressure on valuations in the mainland will inevitably have an effect on Hong Kong’s equity market, further aggravating capital outflows. In the worst-case scenario, steeper outflows combined with rising rates (which make mortgages more expensive) could trigger a collapse of the local property market (Chart 9).

In summary, whilst it is unlikely that the HKMA will abandon its decades old peg to the USD in the short term, recent developments will add to the growth headwinds of the region. The risks remain to the downside if speculative attacks on the HKD last longer than expected and trigger more capital outflows from Hong Kong.

The authorities’ quiet confidence may be well justified. For example, during the Asian Financial crisis, there was significant pressure from speculators who believed a devaluation of the HKD was inevitable. The concern at the time was that a strengthening dollar would hurt Hong Kong’s economy, which was experiencing outflows stemming from its exposure to volatile Asian markets. The HKMA’s intervention was both vigorous and merciless, driving up the 3M Hibor to almost 20% and leading to a -25% fall in the Hang Seng Index. It was also effective in driving out the short-sellers.

In 2011, US based hedge fund manager Bill Ackerman lodged a speculative attack that incoming Chief Executive CY Leung would devalue the HKD in order to curb hot money inflows from the mainland, which were fueling a property bubble in the region, thereby worsening social tensions. However, much to Ackerman’s dismay, CY Leung pledged to keep the HKD’s linked exchange rate mechanism untouched. Money was lost.

Stable HKD and higher interest rates pose risks to local economy

Admittedly, it is not hard for the HKMA to keep the HKD below the 7.85 level, but the authorities might pay a cost of a fast hike in interbank interest rate. Despite Hong Kong having maintained a very prudent fiscal policy, Hong Kong credit boom has made the economy’s total debt levels are amongst the highest in Asia, second only to Japan (Chart 6). However, unlike Japan, the bulk of this indebtedness is accounted for by corporates (Chart 7). The risks in the corporate bond market are on the rise.

Moreover, rising interest rates and a stronger HKD will make it expensive for Chinese corporates to seek financing in Hong Kong. In fact, Hong Kong has become increasingly exposed to China’s economy. For example, loans for use outside Hong Kong have rocketed on the back of falling interest rates since 2009 (Chart 8). Banks have significantly increased their exposure to China, as we have seen that as a result of tightening mainland banking regulations, mainland companies are increasingly seeking funding in Hong Kong for their projects, especially for the real-estate sector and local government entities.

Also Hong Kong is not exempt from spill-overs from volatility in China’s financial markets. Downward pressure on valuations in the mainland will inevitably have an effect on Hong Kong’s equity market, further aggravating capital outflows. In the worst-case scenario, steeper outflows combined with rising rates (which make mortgages more expensive) could trigger a collapse of the local property market (Chart 9).

In summary, whilst it is unlikely that the HKMA will abandon its decades old peg to the USD in the short term, recent developments will add to the growth headwinds of the region. The risks remain to the downside if speculative attacks on the HKD last longer than expected and trigger more capital outflows from Hong Kong.

[1] Steve Hanke, “Why Argentina did not have a currency board”, Central Banking Journal, Vol.18, Feb 2008.

[1] Steve Hanke, “Why Argentina did not have a currency board”, Central Banking Journal, Vol.18, Feb 2008.