David Marsh: How New Reserve Currency System Could Resemble a ‘Cold War’

2016-05-20 IMI LONDON — The world’s multicurrency reserve system now shaping up is likely to be significantly more volatile than the de facto arrangement linking the dollar and Deutsche mark that existed until 1999, and the dollar-euro system that has existed since then.

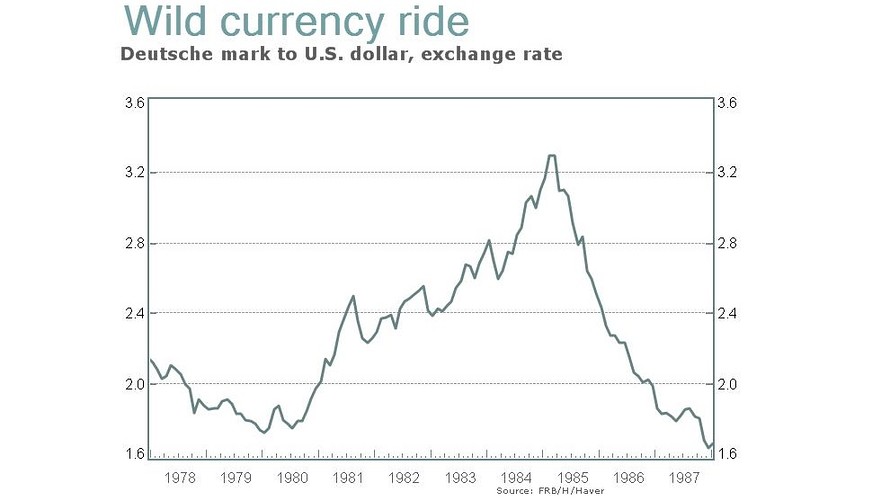

This doesn’t mean that we are likely to see currency fluctuations as extreme as the near-doubling of the dollar against the D-mark between 1979 (when the U.S. moved to extreme monetary tightening under Fed Chairman Paul Volcker) and the early 1980s. The Volcker squeeze was responsible for the political demise of Jimmy Carter in the U.S., Valery Giscard d’Estaing in France and Helmut Schmidt in Germany.

What we will see is radical multiple uncertainty caused by the oscillations of five major reserve currencies — the dollar, euro, yen, sterling and renminbi — each subject to the vagaries of their independent and uncoordinated financial and economic systems.

This need not be vastly unsettling. Indeed, it could be that, after some currency swings, the system will become relatively stable, with offsetting ups and downs of currencies and economic cycles. There may be some resemblance to the MIRV multiple-warhead nuclear missiles deployed by the U.S. and Soviet Union (and to a lesser extent by Britain, France and China) during the hot phase of the Cold War in the 1970s.

Denis Healey, U.K. defense secretary during part of this time, used to say, in the best spirit of nuclear deterrence, that uncertainty associated with the delightfully named multiple independently targetable re-entry vehicles was stabilizing because the adversary would be perpetually on tenterhooks. No one knew exactly which cities were targeted or indeed whether all the warheads were armed.

On the other hand, if communications went awry, signals were misunderstood, or reckless politicians and foolish advisers took control, the accumulation of nuclear tinder could have led to destruction putting the first two world wars in the shade. The same is true of the annihilation that could take place if today’s monetary commanders veer too far off course.

Some fundamental fears about the safety of the monetary system focus on China. Beijing has won a battle to bring the yuan into the International Monetary Fund’s special drawing right from Oct. 1. Joining the other four main reserve currencies brings kudos and economic benefits. But it presupposes that the Chinese government can continue liberalization, both internally and in external interactions, without unduly disrupting Communist Party control.

Chinese leaders have pressed ahead with technocratic reforms in areas like foreign-exchange trading and interest rates but have hesitated to interfere with more overtly politicized parts of the economy, such as state-owned enterprises, the disorderly unwinding of which could have currency repercussions.

As Ravi Menon, managing director of the Monetary Authority of Singapore, noted in a lecture sponsored by the Official Monetary and Financial Institutions Forum in London on May 5, China is juggling three balls at the same time: “grappling with the challenge of managing a growth slowdown, addressing vulnerabilities in its financial system, and implementing structural reforms.”

The other big imponderable is the euro area.

Mario Draghi, president of the European Central Bank, said correctly in Frankfurt last week that the euro is at the center of a “global excess of savings”, reflected in the large current-account surpluses of its principal creditor members, Germany and the Netherlands. Taking into account the sizeable surpluses of other noneuro countries such as Denmark, Sweden and Switzerland whose currencies are part of the wider euro area (and would undoubtedly join if weaker countries left), Europe is home to some of the world’s largest current-account surpluses.

This is especially striking now that large Middle East oil exporters have moved into deficit.

The euro is too weak for the German, Dutch and Swiss economies, but too strong for the southern members trying to recover from debts and unemployment — not a good signal for euro stability in coming years. With euro interest rates expected to remain low indefinitely, the high point for the euro’s role in monetary reserves may have occurred in 2009. According to International Monetary Fund figures, its share of official foreign-exchange holdings has slipped since then by more than 8 percentage points, from 28% to 19.9%.

Former Defense Secretary Healey’s aphorism on MIRVs may be fitting. The Big Five currencies’ strengths and weaknesses may cancel out, just as happened with the five nuclear powers in the Cold War. But, in establishing whether this is true, we may be in for a bumpy ride.

LONDON — The world’s multicurrency reserve system now shaping up is likely to be significantly more volatile than the de facto arrangement linking the dollar and Deutsche mark that existed until 1999, and the dollar-euro system that has existed since then.

This doesn’t mean that we are likely to see currency fluctuations as extreme as the near-doubling of the dollar against the D-mark between 1979 (when the U.S. moved to extreme monetary tightening under Fed Chairman Paul Volcker) and the early 1980s. The Volcker squeeze was responsible for the political demise of Jimmy Carter in the U.S., Valery Giscard d’Estaing in France and Helmut Schmidt in Germany.

What we will see is radical multiple uncertainty caused by the oscillations of five major reserve currencies — the dollar, euro, yen, sterling and renminbi — each subject to the vagaries of their independent and uncoordinated financial and economic systems.

This need not be vastly unsettling. Indeed, it could be that, after some currency swings, the system will become relatively stable, with offsetting ups and downs of currencies and economic cycles. There may be some resemblance to the MIRV multiple-warhead nuclear missiles deployed by the U.S. and Soviet Union (and to a lesser extent by Britain, France and China) during the hot phase of the Cold War in the 1970s.

Denis Healey, U.K. defense secretary during part of this time, used to say, in the best spirit of nuclear deterrence, that uncertainty associated with the delightfully named multiple independently targetable re-entry vehicles was stabilizing because the adversary would be perpetually on tenterhooks. No one knew exactly which cities were targeted or indeed whether all the warheads were armed.

On the other hand, if communications went awry, signals were misunderstood, or reckless politicians and foolish advisers took control, the accumulation of nuclear tinder could have led to destruction putting the first two world wars in the shade. The same is true of the annihilation that could take place if today’s monetary commanders veer too far off course.

Some fundamental fears about the safety of the monetary system focus on China. Beijing has won a battle to bring the yuan into the International Monetary Fund’s special drawing right from Oct. 1. Joining the other four main reserve currencies brings kudos and economic benefits. But it presupposes that the Chinese government can continue liberalization, both internally and in external interactions, without unduly disrupting Communist Party control.

Chinese leaders have pressed ahead with technocratic reforms in areas like foreign-exchange trading and interest rates but have hesitated to interfere with more overtly politicized parts of the economy, such as state-owned enterprises, the disorderly unwinding of which could have currency repercussions.

As Ravi Menon, managing director of the Monetary Authority of Singapore, noted in a lecture sponsored by the Official Monetary and Financial Institutions Forum in London on May 5, China is juggling three balls at the same time: “grappling with the challenge of managing a growth slowdown, addressing vulnerabilities in its financial system, and implementing structural reforms.”

The other big imponderable is the euro area.

Mario Draghi, president of the European Central Bank, said correctly in Frankfurt last week that the euro is at the center of a “global excess of savings”, reflected in the large current-account surpluses of its principal creditor members, Germany and the Netherlands. Taking into account the sizeable surpluses of other noneuro countries such as Denmark, Sweden and Switzerland whose currencies are part of the wider euro area (and would undoubtedly join if weaker countries left), Europe is home to some of the world’s largest current-account surpluses.

This is especially striking now that large Middle East oil exporters have moved into deficit.

The euro is too weak for the German, Dutch and Swiss economies, but too strong for the southern members trying to recover from debts and unemployment — not a good signal for euro stability in coming years. With euro interest rates expected to remain low indefinitely, the high point for the euro’s role in monetary reserves may have occurred in 2009. According to International Monetary Fund figures, its share of official foreign-exchange holdings has slipped since then by more than 8 percentage points, from 28% to 19.9%.

Former Defense Secretary Healey’s aphorism on MIRVs may be fitting. The Big Five currencies’ strengths and weaknesses may cancel out, just as happened with the five nuclear powers in the Cold War. But, in establishing whether this is true, we may be in for a bumpy ride.