Sumedh Deorukhkar, Alvaro Ortiz, Tomasa Rodrigo and Xia Le: One Belt One Road-What's in It for Latin America

2018-01-30 IMI Latam countries are currently not members of OBOR. That said, China’s impact on Latam’s regional development has been significant over the past decade. The region’s trade growth with China has outstripped that with rest of the world since 2000. Natural resources account for largest share of China’s imports as well as direct investments into Latam. Its exports to China are mainly characterized by primary products, such as crude oil, iron and steel, copper, solid fuels, scrap aluminium, precious metals, meat, etc. With regards Chinese investments, between 2015-2016, Latam accounted for 14% share in direct investments in energy sector from China while its share in transportation and metals was 8%.

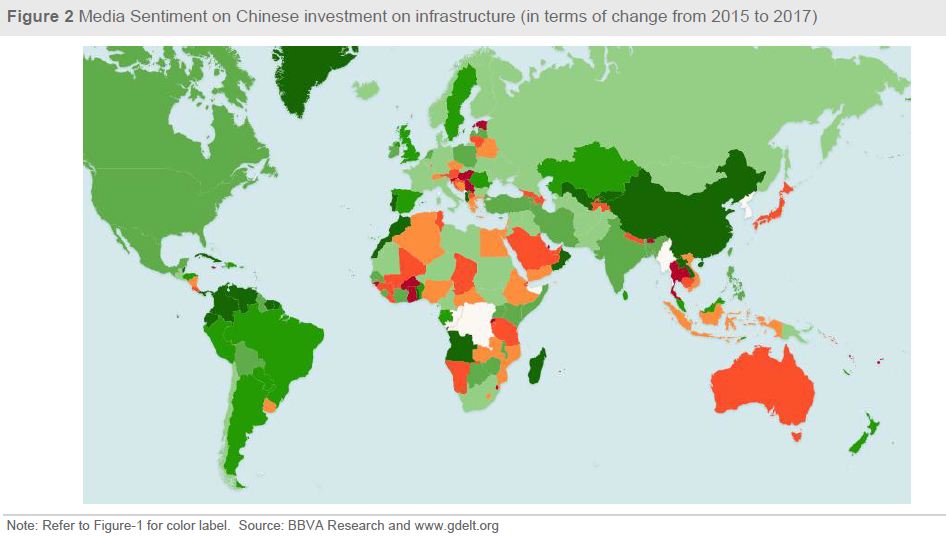

Latam’s involvement in the OBOR initiative can provide several benefits for the region. OBOR's contours have been left flexible by design with investments spanning beyond just the infrastructure sector. This presents an opportunity for Latam to 1) sustain its commodity export demand along OBOR, 2) reduce its commodity dependency, boost productivity and move up the export value chain and 3) increase opportunities for bilateral financing from China. The heavy dependence on commodity exports has made Latam vulnerable to a slowdown in China’s economic growth and its rebalancing efforts. In this context, and also in the wake of heightened concerns over protectionist actions from the Trump administration, OBOR participation would help create room for more balanced development in Latam economies. Reassuringly, we find that the evolution of media sentiment of Chinese investment in infrastructure has improved across all Latam countries in 2017 compared to 2015 (Figure 2).

Latam countries are currently not members of OBOR. That said, China’s impact on Latam’s regional development has been significant over the past decade. The region’s trade growth with China has outstripped that with rest of the world since 2000. Natural resources account for largest share of China’s imports as well as direct investments into Latam. Its exports to China are mainly characterized by primary products, such as crude oil, iron and steel, copper, solid fuels, scrap aluminium, precious metals, meat, etc. With regards Chinese investments, between 2015-2016, Latam accounted for 14% share in direct investments in energy sector from China while its share in transportation and metals was 8%.

Latam’s involvement in the OBOR initiative can provide several benefits for the region. OBOR's contours have been left flexible by design with investments spanning beyond just the infrastructure sector. This presents an opportunity for Latam to 1) sustain its commodity export demand along OBOR, 2) reduce its commodity dependency, boost productivity and move up the export value chain and 3) increase opportunities for bilateral financing from China. The heavy dependence on commodity exports has made Latam vulnerable to a slowdown in China’s economic growth and its rebalancing efforts. In this context, and also in the wake of heightened concerns over protectionist actions from the Trump administration, OBOR participation would help create room for more balanced development in Latam economies. Reassuringly, we find that the evolution of media sentiment of Chinese investment in infrastructure has improved across all Latam countries in 2017 compared to 2015 (Figure 2).

On the flipside, while substantial benefits could accrue for Latin America from participation in the OBOR initiative, there exist significant economic, financial and technical obstacles to deeper integration between China and Latam, which need to be addressed. Below, we examine China-Latam economic ties in greater detail and explore ways to deepen integration between the two under the OBOR initiative.

Examining China-Latin America trade and investment links

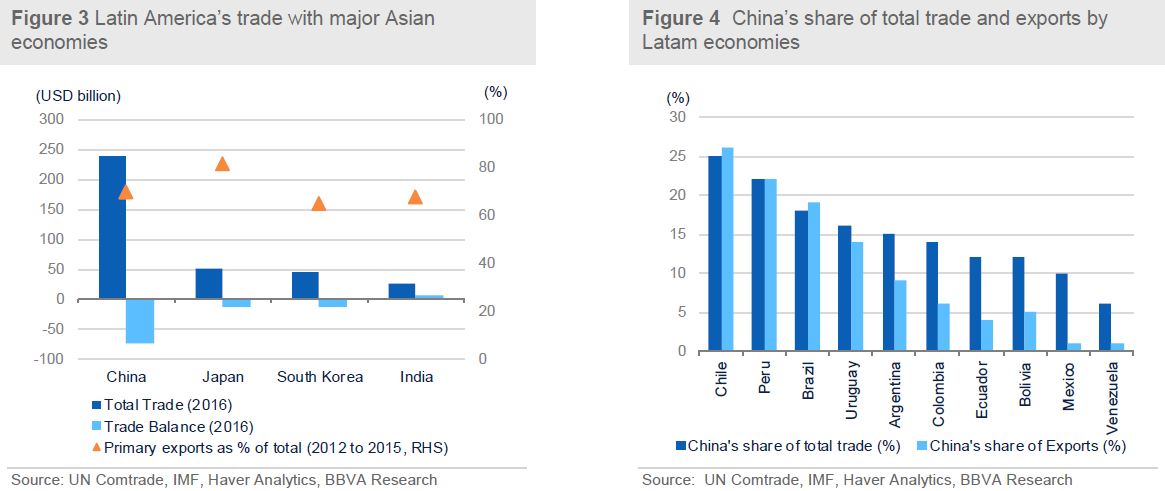

Over the past decade, China has emerged as amongst the key trade partner and investment source for several countries in Latam. The region’s trade with China has boomed over the past decade (See Figure – 3). Amongst Latam economies (See Figure – 4), the share of total trade with China is highest for Chile (25%), followed by Peru (22%), and Brazil (18%). Structural factors define the China-Latam trade pattern. China’s quest for mineral resources and food security makes Argentina, Brazil, Chile and Peru an attractive destination given their vast agriculture and mineral resources. Their exports to China are mainly characterized by primary products. On the other hand, Mexico’s large manufacturing sector makes it a direct competitor of China, which, in part, explains their relatively weak trade linkage.

On the flipside, while substantial benefits could accrue for Latin America from participation in the OBOR initiative, there exist significant economic, financial and technical obstacles to deeper integration between China and Latam, which need to be addressed. Below, we examine China-Latam economic ties in greater detail and explore ways to deepen integration between the two under the OBOR initiative.

Examining China-Latin America trade and investment links

Over the past decade, China has emerged as amongst the key trade partner and investment source for several countries in Latam. The region’s trade with China has boomed over the past decade (See Figure – 3). Amongst Latam economies (See Figure – 4), the share of total trade with China is highest for Chile (25%), followed by Peru (22%), and Brazil (18%). Structural factors define the China-Latam trade pattern. China’s quest for mineral resources and food security makes Argentina, Brazil, Chile and Peru an attractive destination given their vast agriculture and mineral resources. Their exports to China are mainly characterized by primary products. On the other hand, Mexico’s large manufacturing sector makes it a direct competitor of China, which, in part, explains their relatively weak trade linkage.

Latam, given its dependence on commodity exports and a high trade imbalance with China (trade deficit of roughly $80 bn with China in 2016), is especially vulnerable to a potential growth deceleration in the middle kingdom. While China is, by far, Latam’s biggest trade partner in Asia, Latam-China trade has slowed markedly over the past three years led by falling commodity prices and sluggish growth. While Latam’s total trade with China stood slightly shy of $250bn in 2016, average annual bilateral trade growth with China has fallen from +30% yy between 2003-2013 to -5% yy between 2014 and 2016. Similar trends are evident in Latam’s trade growth with other major economies in Asia such as Japan, South Korea and India.

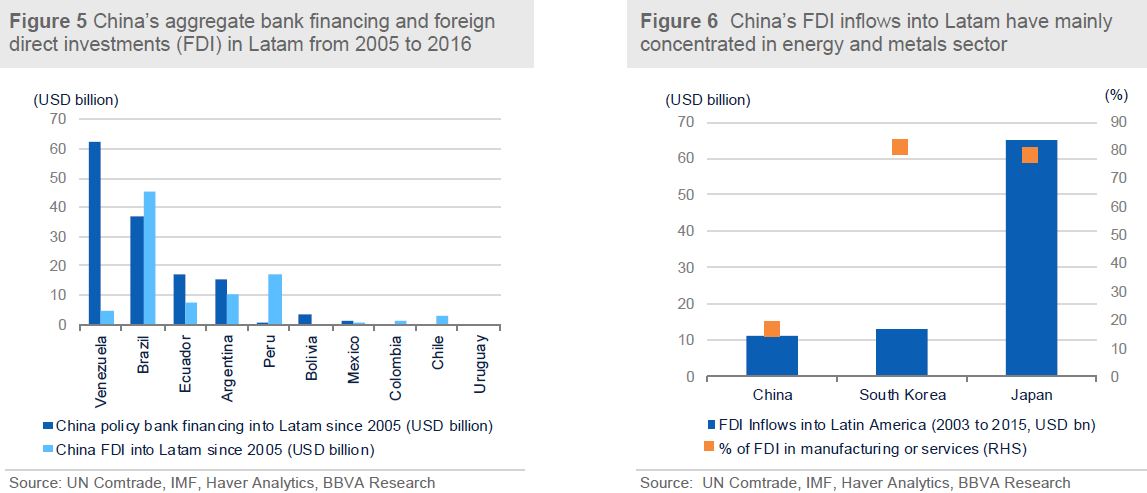

With regards China-Latam investment links, Chinese foreign direct investments (FDI) in Latin America, aren’t uniform and still relatively muted when compared to other Asian investors such as Japan. Amongst Latam countries, Brazil is the largest recipient of investment from China, with an aggregate $45 bn in announcement investments since 2005 (Figure - 5), followed by Peru ($17 bn), and Argentina ($10 bn). Reflecting a similar trend, Chinese financing in Latin America has not been uniform either. While Chinese state owned banks have lent in excess of $140 bn to Latam since 2005, bulk of Chinese financing has been to Venezuela ($62 bn), followed by Brazil ($37 bn), Ecuador ($17 bn) and Argentina ($15 bn). Mexico and Columbia, in particular, have received very little financing since 2005 ($1 bn for Mexico).

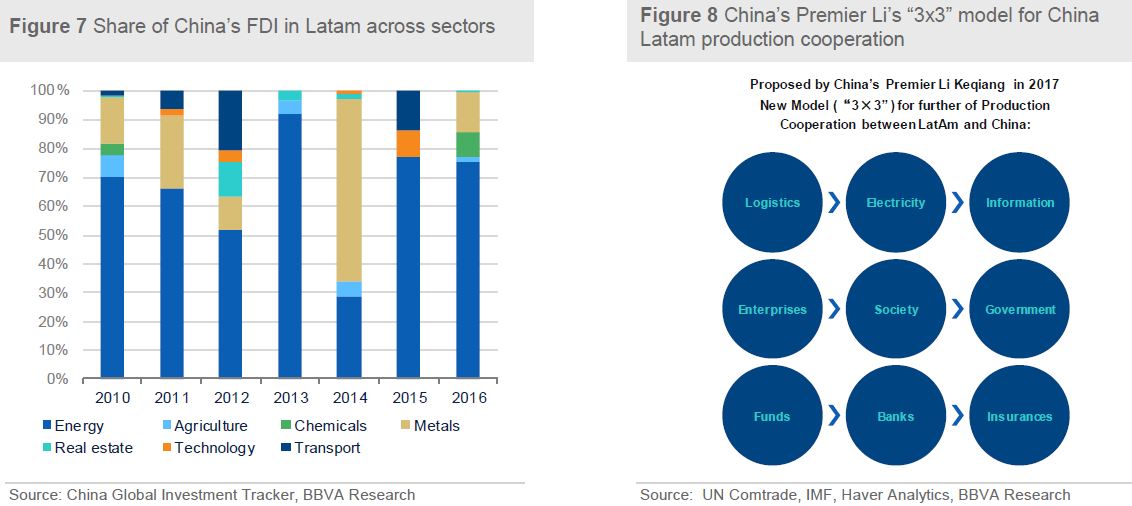

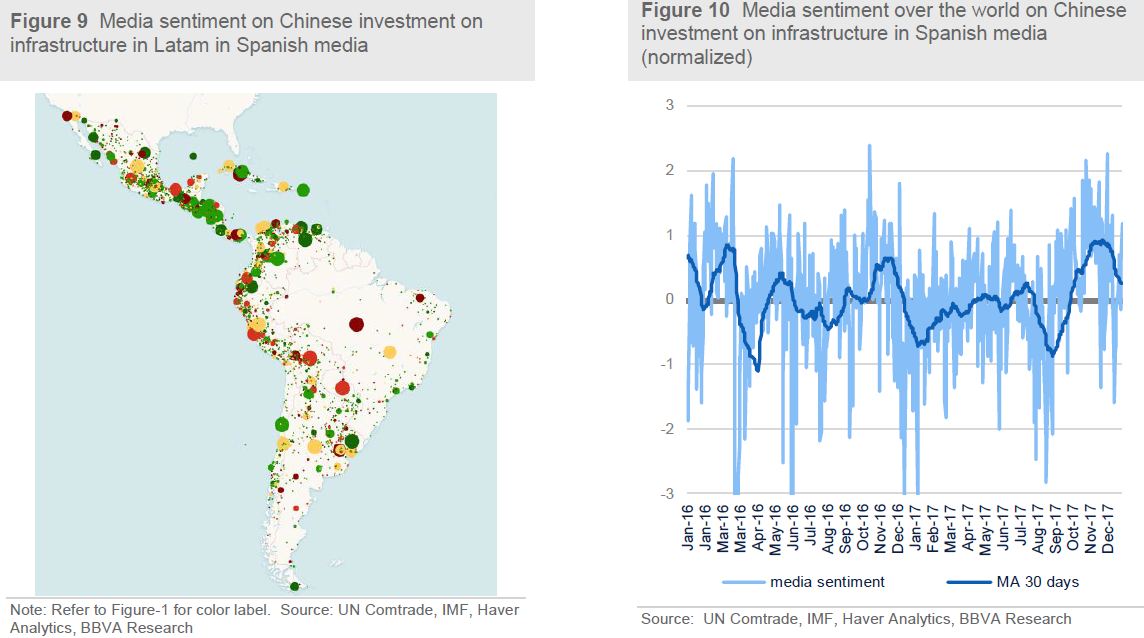

Japan tops Asia as the largest source of FDI into Latam with investments totaling $65 bn between 2013 and 2015. Importantly, 78% of Japanese FDI in Latam was in more labor intensive and productive sectors such as manufacturing and services. In comparison, China’s FDI inflows into Latam have been relatively muted at $11 bn during the same period. More so, bulk of China’s FDI into Latam is in the region’s energy sector with 16% of China’s FDI into manufacturing and services sector (Figures – 6 and 7). Even South Korea’s FDI inflows into Latam during 2013-15 beat China’s at $13 bn with 81% of FDI in manufacturing and services sector. Furthermore, the nature of Chinese investments in Latin America’s energy sector have so far been mainly concentrated in state controlled administrations such as Ecuador and Venezuela, where Chinese SOE’s deal directly with the respective governments.

Latam, given its dependence on commodity exports and a high trade imbalance with China (trade deficit of roughly $80 bn with China in 2016), is especially vulnerable to a potential growth deceleration in the middle kingdom. While China is, by far, Latam’s biggest trade partner in Asia, Latam-China trade has slowed markedly over the past three years led by falling commodity prices and sluggish growth. While Latam’s total trade with China stood slightly shy of $250bn in 2016, average annual bilateral trade growth with China has fallen from +30% yy between 2003-2013 to -5% yy between 2014 and 2016. Similar trends are evident in Latam’s trade growth with other major economies in Asia such as Japan, South Korea and India.

With regards China-Latam investment links, Chinese foreign direct investments (FDI) in Latin America, aren’t uniform and still relatively muted when compared to other Asian investors such as Japan. Amongst Latam countries, Brazil is the largest recipient of investment from China, with an aggregate $45 bn in announcement investments since 2005 (Figure - 5), followed by Peru ($17 bn), and Argentina ($10 bn). Reflecting a similar trend, Chinese financing in Latin America has not been uniform either. While Chinese state owned banks have lent in excess of $140 bn to Latam since 2005, bulk of Chinese financing has been to Venezuela ($62 bn), followed by Brazil ($37 bn), Ecuador ($17 bn) and Argentina ($15 bn). Mexico and Columbia, in particular, have received very little financing since 2005 ($1 bn for Mexico).

Japan tops Asia as the largest source of FDI into Latam with investments totaling $65 bn between 2013 and 2015. Importantly, 78% of Japanese FDI in Latam was in more labor intensive and productive sectors such as manufacturing and services. In comparison, China’s FDI inflows into Latam have been relatively muted at $11 bn during the same period. More so, bulk of China’s FDI into Latam is in the region’s energy sector with 16% of China’s FDI into manufacturing and services sector (Figures – 6 and 7). Even South Korea’s FDI inflows into Latam during 2013-15 beat China’s at $13 bn with 81% of FDI in manufacturing and services sector. Furthermore, the nature of Chinese investments in Latin America’s energy sector have so far been mainly concentrated in state controlled administrations such as Ecuador and Venezuela, where Chinese SOE’s deal directly with the respective governments.

OBOR framework to help fast-track Chinese Premier Li’s proposed “3x3” Model that aims to boost China-Latam collaboration on production capacity

Realizing the need for China and Latam to expand cooperation beyond just trading commodities, in mid-2017, Chinese Premier Li proposed a “3x3” model for boosting China-Latam collaboration on production capacity in new fields such as logistics, infrastructure, energy and information (Figure – 8). The three-pronged model involves – 1) meeting domestic demand in Latam through three passages of logistics, power and information, 2) following the rules of market economy and cooperating to achieving positive interaction among enterprises, society and government, 3) expanding the three financial channels of funds, credit and insurance. Potential involvement of Latam economies in the OBOR framework should help fast-track implementation of the “3x3” model and in turn make bilateral ties between China and Latam far more resilient.

Importantly, China may be willing to foot a greater share of the financing bill of infrastructure projects in Latam if Latin countries show greater openness to OBOR. A case in point is the railway project linking the Brazilian port of Santos and Llo in Peru, which promises to transform trade links across Latam by linking the Atlantic and the Pacific by reducing time required for cargo from Brazil to reach the Pacific by nearly four weeks. The project is estimated to cost $13 bn to $15 bn and could carry 10 million tonnes of cargo each year. The project has received the backing of Peru, Paraguay, Bolivia and Argentina, while Brazil seems less forthcoming given its uncertain fiscal situation. Brazilian soya and iron-ore producers stand to benefit from the project. Brazil is China’s biggest supplier of Soya. China’s quest to secure food and energy resources explains its keenness to improve access with Latin America and back multinational infrastructure projects across the region. In this regard, recent years has seen big Chinese engineering, procurement and construction companies increasing their presence in the region (See Table - 1). Latin American economies are looking at Chinese finance for large multinational infrastructure projects that would enhance physical integration of Latam economies.

OBOR framework to help fast-track Chinese Premier Li’s proposed “3x3” Model that aims to boost China-Latam collaboration on production capacity

Realizing the need for China and Latam to expand cooperation beyond just trading commodities, in mid-2017, Chinese Premier Li proposed a “3x3” model for boosting China-Latam collaboration on production capacity in new fields such as logistics, infrastructure, energy and information (Figure – 8). The three-pronged model involves – 1) meeting domestic demand in Latam through three passages of logistics, power and information, 2) following the rules of market economy and cooperating to achieving positive interaction among enterprises, society and government, 3) expanding the three financial channels of funds, credit and insurance. Potential involvement of Latam economies in the OBOR framework should help fast-track implementation of the “3x3” model and in turn make bilateral ties between China and Latam far more resilient.

Importantly, China may be willing to foot a greater share of the financing bill of infrastructure projects in Latam if Latin countries show greater openness to OBOR. A case in point is the railway project linking the Brazilian port of Santos and Llo in Peru, which promises to transform trade links across Latam by linking the Atlantic and the Pacific by reducing time required for cargo from Brazil to reach the Pacific by nearly four weeks. The project is estimated to cost $13 bn to $15 bn and could carry 10 million tonnes of cargo each year. The project has received the backing of Peru, Paraguay, Bolivia and Argentina, while Brazil seems less forthcoming given its uncertain fiscal situation. Brazilian soya and iron-ore producers stand to benefit from the project. Brazil is China’s biggest supplier of Soya. China’s quest to secure food and energy resources explains its keenness to improve access with Latin America and back multinational infrastructure projects across the region. In this regard, recent years has seen big Chinese engineering, procurement and construction companies increasing their presence in the region (See Table - 1). Latin American economies are looking at Chinese finance for large multinational infrastructure projects that would enhance physical integration of Latam economies.

OBOR could better enable Latam to tap Asia in wake of rising US protectionism

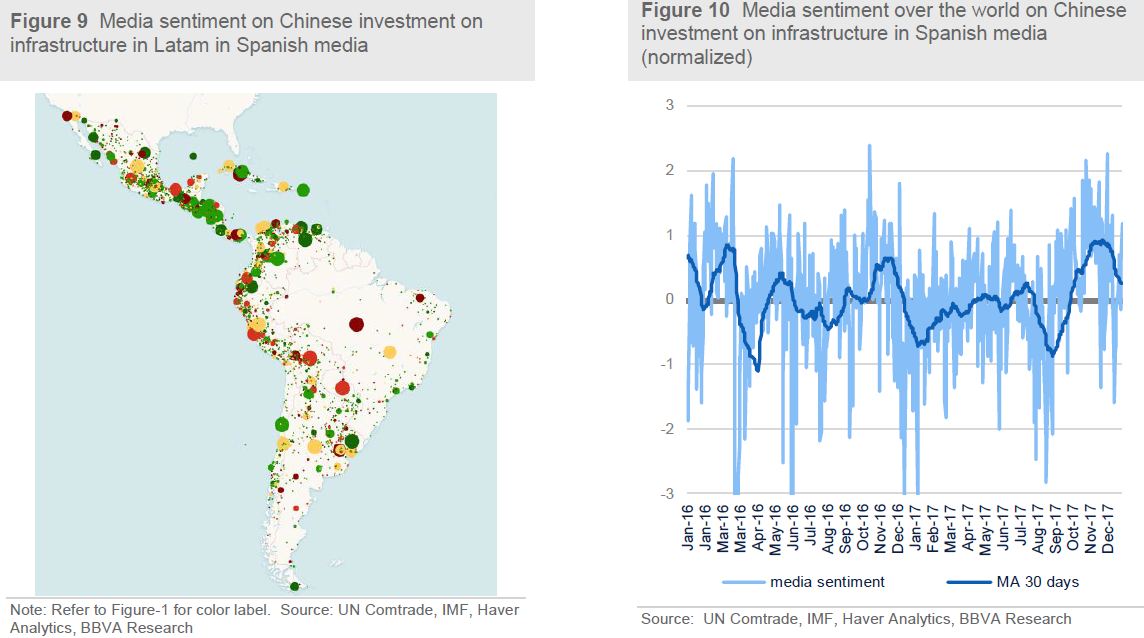

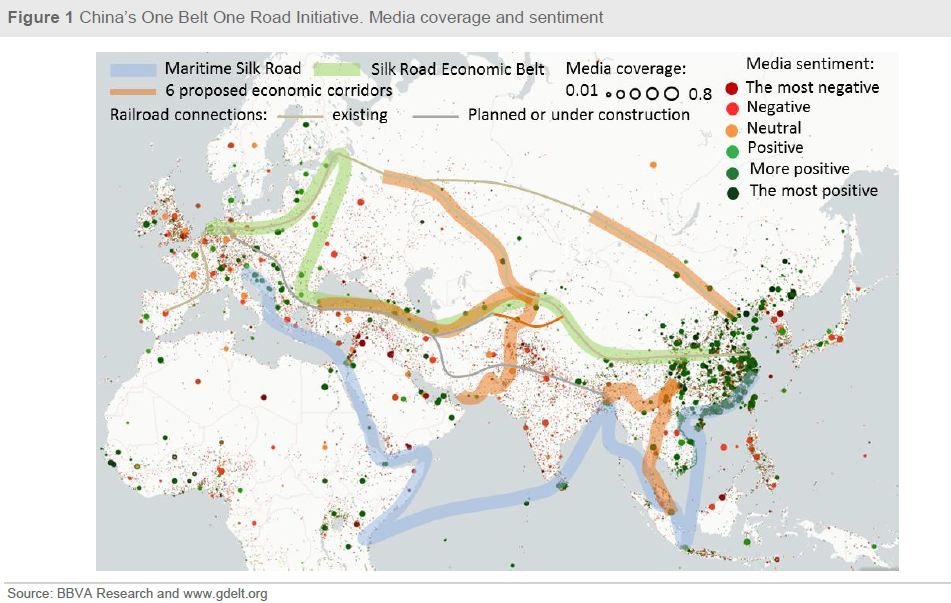

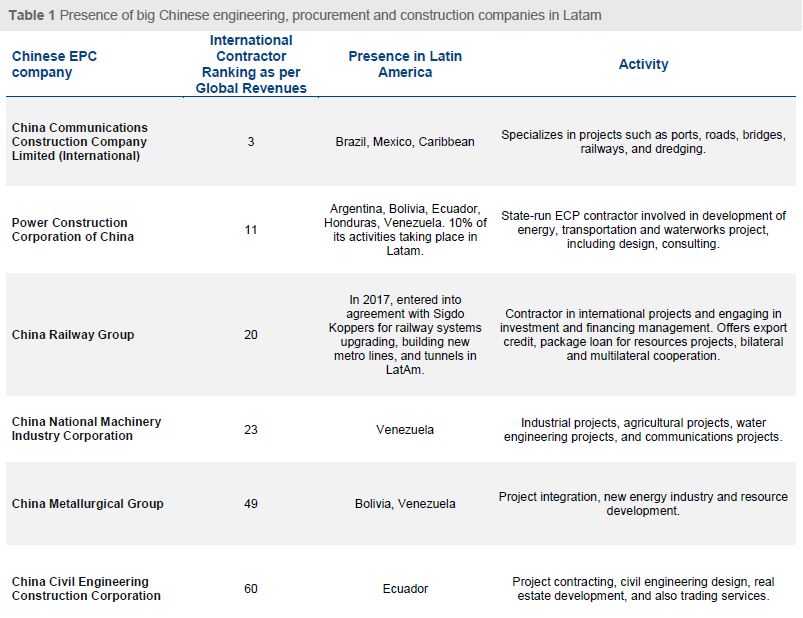

Prospects of deeper integration between Asia and Latin America have increased in the wake of protectionist rhetoric and actions by US President Donald Trump. Under Trump’s leadership, US administration has abandoned the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) agreement, of which Mexico, Chile and Peru were a part; NAFTA renegotiations process has been rocky, escalated threats of unilateral action to reduce US trade deficits, criticised WTO’s dispute settlement process and the new US Tax reforms bill includes several protectionist overtures. Such actions upend economic ties between the US and Latam economies, particularly Mexico, Chile, Colombia, Peru, Bolivia and Uruguay. These economies have close ties with the US – most have a Free Trade Agreement with the US - and are strong supporters of the global trade order. The recent shifts in US foreign policy strategy towards greater protectionism and the related concerns over global economic instability has provided an opportunity for China to promote itself as the torch bearer of globalization, free trade and open markets. In fact, our analysis of the Spanish media suggests that media coverage has increased and sentiment has improved in Latam countries about Chinese investment in infrastructure across Latam if we compare news media one year after Trump’s election as US President on 8th November 2016 to that in the year before (Figure 9). However, this improvement in sentiment is not observed at the global level (Figure 10).

OBOR could better enable Latam to tap Asia in wake of rising US protectionism

Prospects of deeper integration between Asia and Latin America have increased in the wake of protectionist rhetoric and actions by US President Donald Trump. Under Trump’s leadership, US administration has abandoned the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) agreement, of which Mexico, Chile and Peru were a part; NAFTA renegotiations process has been rocky, escalated threats of unilateral action to reduce US trade deficits, criticised WTO’s dispute settlement process and the new US Tax reforms bill includes several protectionist overtures. Such actions upend economic ties between the US and Latam economies, particularly Mexico, Chile, Colombia, Peru, Bolivia and Uruguay. These economies have close ties with the US – most have a Free Trade Agreement with the US - and are strong supporters of the global trade order. The recent shifts in US foreign policy strategy towards greater protectionism and the related concerns over global economic instability has provided an opportunity for China to promote itself as the torch bearer of globalization, free trade and open markets. In fact, our analysis of the Spanish media suggests that media coverage has increased and sentiment has improved in Latam countries about Chinese investment in infrastructure across Latam if we compare news media one year after Trump’s election as US President on 8th November 2016 to that in the year before (Figure 9). However, this improvement in sentiment is not observed at the global level (Figure 10).

As Latam looks to gain deeper access to key Asian markets in the wake of US protectionism, the OBOR platform would enable China to better promote its financial institutions and trade integration strategy across Latam. The OBOR framework would help streamline the influence on Chinese financing in Latam. China led Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) and the New Development Bank (BRICS Bank) present an alternative development funding source for Latin America at a time when the Trump Administration eyes international financial institutions such as the World Bank and IMF with suspicion. Besides, Chinese policy banks can exploit untapped financing opportunities across Latin America. In this regard, China and Mexico formed a joint fund for infrastructure projects in late 2016.

Further Chinese policy banks are looking at deepening participation in infrastructure projects, including ports, highways, railways in Argentina, Brazil, Colombia and Peru. The China Development Bank (CDB) and China Export-Import Bank have invested an aggregate $25 bn in Brazil since 2015.

OBOR would also underpin Chinese FDI into Latam, which remains modest so far and heavily skewed towards the energy sector as explained earlier. Reassuringly, off late, Chinese FDI in manufacturing, particularly automobiles, have seen a modest pick-up. Chinese automakers JAC Motors, BAIC and Chery have set up production plants in Brazil and Argentina. Last Feb, JAC motors announced $212 mn investment in Mexico. Domestic investments in manufacturing sector should help improve China’s image in Latam, which helps ease concerns that Chinese competition hurts Latam’s domestic manufacturing sector.

As Latam looks to gain deeper access to key Asian markets in the wake of US protectionism, the OBOR platform would enable China to better promote its financial institutions and trade integration strategy across Latam. The OBOR framework would help streamline the influence on Chinese financing in Latam. China led Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) and the New Development Bank (BRICS Bank) present an alternative development funding source for Latin America at a time when the Trump Administration eyes international financial institutions such as the World Bank and IMF with suspicion. Besides, Chinese policy banks can exploit untapped financing opportunities across Latin America. In this regard, China and Mexico formed a joint fund for infrastructure projects in late 2016.

Further Chinese policy banks are looking at deepening participation in infrastructure projects, including ports, highways, railways in Argentina, Brazil, Colombia and Peru. The China Development Bank (CDB) and China Export-Import Bank have invested an aggregate $25 bn in Brazil since 2015.

OBOR would also underpin Chinese FDI into Latam, which remains modest so far and heavily skewed towards the energy sector as explained earlier. Reassuringly, off late, Chinese FDI in manufacturing, particularly automobiles, have seen a modest pick-up. Chinese automakers JAC Motors, BAIC and Chery have set up production plants in Brazil and Argentina. Last Feb, JAC motors announced $212 mn investment in Mexico. Domestic investments in manufacturing sector should help improve China’s image in Latam, which helps ease concerns that Chinese competition hurts Latam’s domestic manufacturing sector.

Deeper integration within Latam is key to ensure that the region benefits from OBOR

With Asian economies enjoying relatively robust growth, closer Asia-Latam trade links can serve as a tailwind and promote sustainable growth for Latin American economies, which face sluggish growth and high political uncertainty. Latam economies will look at OBOR as a means to enhance market access to Asia’s largest economies, particularly in areas where Latam has a comparative advantage such as food products and processed metals. That said, Latin America needs to focus on regional integration if it wants a stronger economic and political basis to negotiate with Asia. Forming a clear strategy and mutual negotiating positions is key for Latin America to fully benefit from its integration with Asia. In this context, enabling closer linkages between Latin America’s two main trading blocs, MERCOSUR (Argentina, Paraguay, Brazil and Uruguay, with Venezuela recently suspended) and the Pacific Alliance (Mexico, Chile, Peru, and Colombia), through regional agreements could strengthen Latin America’s integration with Asia. Internal divisions amongst Latam countries into the two distinct groups – Pacific Alliance and MERCOSUR – hamper deeper integration among member countries and constrain their ability to negotiate trade deals with Asia as a bloc.

Latam economies need to build a consensus position on regulatory standards, customs norms and rules of origin before negotiating with Asian partners. Such common stand on market access issues would strengthen their bargaining position with Asia. Furthermore, deeper integration within Latam would also ensure a broader and more effective spillover of benefits of OBOR and Latam-Asia trade investment links across Latam. Recent political developments in Brazil and Argentina, characterized by more business-friendly administrations, promises closer linkages between the Pacific Alliance and MERCOSUR. A series of high level official meetings between the two groups underscores this hope.

Latam’s interest in Asia’s regional trade agreements suggests its keenness to participate in OBOR projects

Latam’s rising interest in trade agreements involving Asian economies underpins the prospects of Latam’s participation in OBOR related projects going forward. The Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) which includes all major Asian economies (10 ASEAN economies and Australia, China, India, Japan, South Korea and New Zealand) has recently seen interest expressed by Chile, Mexico and Peru. Furthermore, the Pacific Alliance has signed a cooperation agreement with ASEAN covering wide range of policy areas, in turn paving the way for a potential trade deal in the future. In addition, while Argentina and Brazil are, so far, keeping their distance from TPP renegotiations, various alternatives for a revamped TPP are seeing different subsets of Latam economies willing to participate. Latam’s active involvement in OBOR projects, should, in turn, further promote such multilateral trade negotiations between Asia-Latam and strengthen trade and investment integration.

Latam’s potential involvement in the One Belt One Road initiative holds much promise, although not without its share of challenges

Substantial benefits could accrue for Latin America from participation OBOR initiative although the economic, financial and technical obstacles are significant as well. Host country circumstances play an important role in determining the success rate of China's foreign investments along the OBOR. Frail fiscal finances and parlous political situation in some Latam economies, particularly Brazil and Venezuela, would undermine Latam’s wholehearted participation in OBOR in the near term. As a key source of funding for OBOR, Chinese financial institutions thus have a credit risk exposure from implementation risks in such countries with a weak credit matrix, which could erode banks’ asset quality and increase contingent liabilities for the Chinese government. All in all, Latam’s future involvement in the One Belt One Road initiative holds much promise, although not without its share of challenges and caveats. Technical issues such as economic viability, engineering and environmental assessment are equally crucial for commencement of infrastructure projects in Latam. Environmental threats as well as high construction costs, have, in the past, rendered potential multinational infrastructure projects in Latam impractical despite their benefits.

Deeper integration within Latam is key to ensure that the region benefits from OBOR

With Asian economies enjoying relatively robust growth, closer Asia-Latam trade links can serve as a tailwind and promote sustainable growth for Latin American economies, which face sluggish growth and high political uncertainty. Latam economies will look at OBOR as a means to enhance market access to Asia’s largest economies, particularly in areas where Latam has a comparative advantage such as food products and processed metals. That said, Latin America needs to focus on regional integration if it wants a stronger economic and political basis to negotiate with Asia. Forming a clear strategy and mutual negotiating positions is key for Latin America to fully benefit from its integration with Asia. In this context, enabling closer linkages between Latin America’s two main trading blocs, MERCOSUR (Argentina, Paraguay, Brazil and Uruguay, with Venezuela recently suspended) and the Pacific Alliance (Mexico, Chile, Peru, and Colombia), through regional agreements could strengthen Latin America’s integration with Asia. Internal divisions amongst Latam countries into the two distinct groups – Pacific Alliance and MERCOSUR – hamper deeper integration among member countries and constrain their ability to negotiate trade deals with Asia as a bloc.

Latam economies need to build a consensus position on regulatory standards, customs norms and rules of origin before negotiating with Asian partners. Such common stand on market access issues would strengthen their bargaining position with Asia. Furthermore, deeper integration within Latam would also ensure a broader and more effective spillover of benefits of OBOR and Latam-Asia trade investment links across Latam. Recent political developments in Brazil and Argentina, characterized by more business-friendly administrations, promises closer linkages between the Pacific Alliance and MERCOSUR. A series of high level official meetings between the two groups underscores this hope.

Latam’s interest in Asia’s regional trade agreements suggests its keenness to participate in OBOR projects

Latam’s rising interest in trade agreements involving Asian economies underpins the prospects of Latam’s participation in OBOR related projects going forward. The Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) which includes all major Asian economies (10 ASEAN economies and Australia, China, India, Japan, South Korea and New Zealand) has recently seen interest expressed by Chile, Mexico and Peru. Furthermore, the Pacific Alliance has signed a cooperation agreement with ASEAN covering wide range of policy areas, in turn paving the way for a potential trade deal in the future. In addition, while Argentina and Brazil are, so far, keeping their distance from TPP renegotiations, various alternatives for a revamped TPP are seeing different subsets of Latam economies willing to participate. Latam’s active involvement in OBOR projects, should, in turn, further promote such multilateral trade negotiations between Asia-Latam and strengthen trade and investment integration.

Latam’s potential involvement in the One Belt One Road initiative holds much promise, although not without its share of challenges

Substantial benefits could accrue for Latin America from participation OBOR initiative although the economic, financial and technical obstacles are significant as well. Host country circumstances play an important role in determining the success rate of China's foreign investments along the OBOR. Frail fiscal finances and parlous political situation in some Latam economies, particularly Brazil and Venezuela, would undermine Latam’s wholehearted participation in OBOR in the near term. As a key source of funding for OBOR, Chinese financial institutions thus have a credit risk exposure from implementation risks in such countries with a weak credit matrix, which could erode banks’ asset quality and increase contingent liabilities for the Chinese government. All in all, Latam’s future involvement in the One Belt One Road initiative holds much promise, although not without its share of challenges and caveats. Technical issues such as economic viability, engineering and environmental assessment are equally crucial for commencement of infrastructure projects in Latam. Environmental threats as well as high construction costs, have, in the past, rendered potential multinational infrastructure projects in Latam impractical despite their benefits.