Sumedh Deorukhkar and Xia Le: One Belt One Road – Progress and Prospects

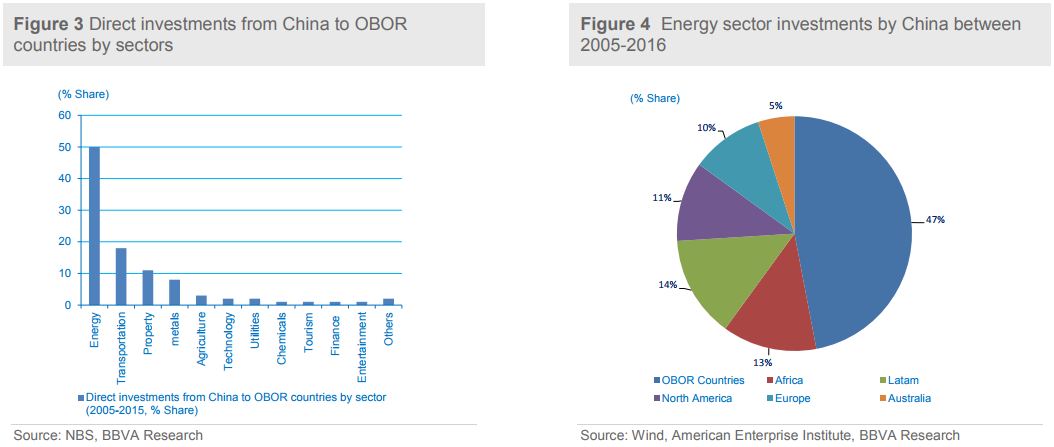

2017-11-10 IMI Not surprisingly, between 2005-2016, China’s foreign direct investments in OBOR countries has mainly concentrated in energy (50%), transportation (18%), property construction (11%), metals mining (8%) and the agriculture (3%) sectors. Such capital allocation, as steered by China’s national policy, has gained traction under OBOR. Chinese M&A deals with OBOR countries in 2015 were 17% of China’s total M&A (at $9.2 bn), a significant jump from just 4% in 2014. So far in 2017, Chinese acquisitions in OBOR countries amount to $33 billion, as compared to $31 billion invested during the whole of 2016 & despite a 42% yy drop in overall outbound M&A from China so far in 2017. This, in turn, reflects the relative immunity of China’s recent capital control measures on OBOR related investment flows.

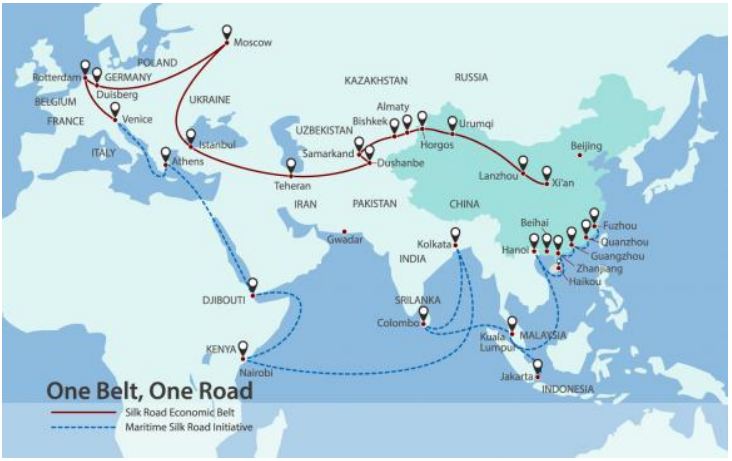

Strategically, OBOR as a ‘brand’ provides the right platform for China to push its ‘soft’ power across Eurasia while underplaying ‘hard’ power tactics. The later, have often sparked geopolitical tensions in the region, particularly those related to the South China Sea, and in turn deepening suspicions and unease amongst other major economies, especially the US and its regional allies. If implemented effectively, the OBOR initiative would strengthen geopolitical and economic linkages between China and recipient countries in commercial trade, capital flows and construction deals. This should help somewhat mitigate China’s perception as a rising threat in the region. The OBOR initiative enables China to project power and naval presence at increasing distances from its shores. For instance, as part of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor under OBOR, the development of the port of Gwadar in Pakistan will act as a key naval base in providing security for China’s maritime trade in the region. Elsewhere, the Strait of Mallaca, to the southwest of South China Sea, facilitates the transit of 84% of all waterborne crude oil and 30% of natural gas imports to China. At its 19th Chinese Communist party Congress, President Xi highlighted the importance of securing China’s sovereignty. In this context, securing the vital maritime trade lifeline through OBOR is a key to ensure national security.

Not surprisingly, between 2005-2016, China’s foreign direct investments in OBOR countries has mainly concentrated in energy (50%), transportation (18%), property construction (11%), metals mining (8%) and the agriculture (3%) sectors. Such capital allocation, as steered by China’s national policy, has gained traction under OBOR. Chinese M&A deals with OBOR countries in 2015 were 17% of China’s total M&A (at $9.2 bn), a significant jump from just 4% in 2014. So far in 2017, Chinese acquisitions in OBOR countries amount to $33 billion, as compared to $31 billion invested during the whole of 2016 & despite a 42% yy drop in overall outbound M&A from China so far in 2017. This, in turn, reflects the relative immunity of China’s recent capital control measures on OBOR related investment flows.

Strategically, OBOR as a ‘brand’ provides the right platform for China to push its ‘soft’ power across Eurasia while underplaying ‘hard’ power tactics. The later, have often sparked geopolitical tensions in the region, particularly those related to the South China Sea, and in turn deepening suspicions and unease amongst other major economies, especially the US and its regional allies. If implemented effectively, the OBOR initiative would strengthen geopolitical and economic linkages between China and recipient countries in commercial trade, capital flows and construction deals. This should help somewhat mitigate China’s perception as a rising threat in the region. The OBOR initiative enables China to project power and naval presence at increasing distances from its shores. For instance, as part of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor under OBOR, the development of the port of Gwadar in Pakistan will act as a key naval base in providing security for China’s maritime trade in the region. Elsewhere, the Strait of Mallaca, to the southwest of South China Sea, facilitates the transit of 84% of all waterborne crude oil and 30% of natural gas imports to China. At its 19th Chinese Communist party Congress, President Xi highlighted the importance of securing China’s sovereignty. In this context, securing the vital maritime trade lifeline through OBOR is a key to ensure national security.

Charting China’s One Belt One Road Initiative

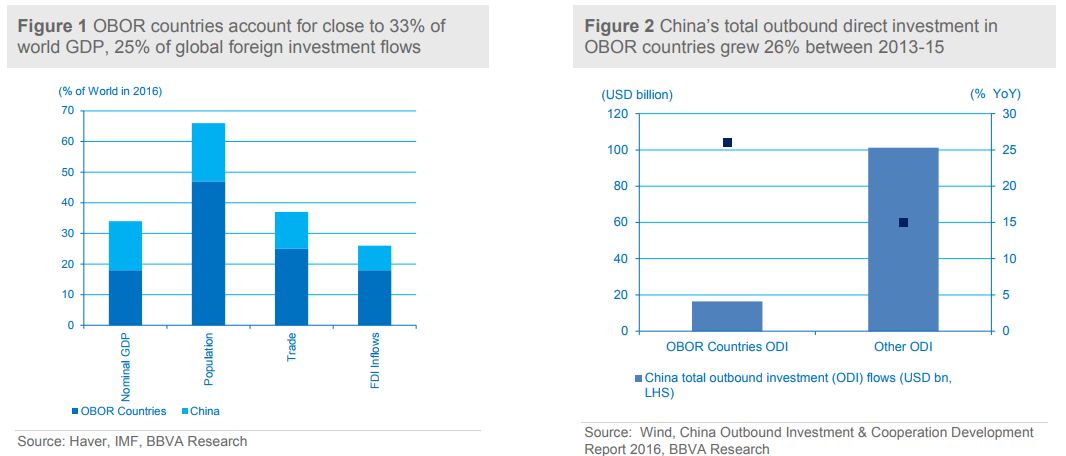

OBOR benefits recipient countries although not without caveats OBOR has opened new opportunities for cooperation and competition for the countries involved, most of which are infrastructure constrained with the lack of public goods undermining growth. Funding constraint is the other related concern with many running current account deficits. While Singapore was the highest recipient of OBOR investments from China, at 31% share of total OBOR investments between 2013 to 2015, developing Asian economies such as Indonesia (9%), Laos (5%),Thailand (4%), Pakistan (3% share), , Vietnam (3%), Cambodia (3%) and Malaysia (3%) top rest of the list. China’s large industrial overcapacity in the wake of on-going economic rebalance, tested expertise in infrastructure, capital account surplus and efforts to secure food and energy resources are well complemented by the need to address infrastructure and funding constraints in most OBOR countries (See Figures – 3 & 4). As per the Asian Development Bank, OBOR countries will need to invest $22.6 tn, or $1.5 tn annually in infrastructure from 2016 to 2030, mainly across electricity generation, transportation and telecommunication sectors. OBOR thus has the potential to deliver infrastructure and in turn higher growth for OBOR countries, particularly where older financial institutions, such as the Asian Development Bank (ADB) in Asia, have fallen short.

Despite having nearly jumped 4-fold to $126 tn by end 2015, the stock Chinese investments as share of total foreign investment stock in OBOR countries is still relatively low at less than 3% when compared to investments by the US (10%) and Europe (50%). Scope to boost Chinese investments is thus huge. The key to plug this gap is for China and the recipient OBOR countries to meet on agreeable terms.

Notwithstanding its long term economic benefits, in the near term, OBOR recipient countries face potential debt sustainability concerns from a pickup in OBOR related inbound investment flows through foreign direct investment and RMB bilateral currency swap agreements. The past three years have seen an increase in indebtedness of OBOR countries, although, so far, the rise in their external debt is much more modest compared to that of domestic debt.

That said, the external debt structure has already seen a shift for economies such as Pakistan, where financing by external non-government entities has risen from 7% of total external debt in 2010 to 14% in 2016. The long gestation period of such investments raises the need for OBOR economies to generate high and sustainable growth for sustaining future debt-servicing capacity. In addition, recipient countries also risk being exposed to less stable and more expensive funding due to increased dependence on Chinese lending while moving away from funding by international financial institutions such as the World Bank and IMF. So far, OBOR funding is mainly reliant on China based institutions. These include Chinese policy banks, China Export and Credit Insurance Corporation, Commercial banks, local financial institutions and local governments. These together have committed around 80% of the total funding (at more than $750 bn) until 2016. The rest includes funds, loan guarantees and grants provided to China by international financial institutions such as the Asia Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), Silk Road fund, New Development Bank for BRICS, Shanghai Cooperation Organization Development Bank, the ADB and World Bank.

OBOR could play a key role in enhancing internationalization of RMB

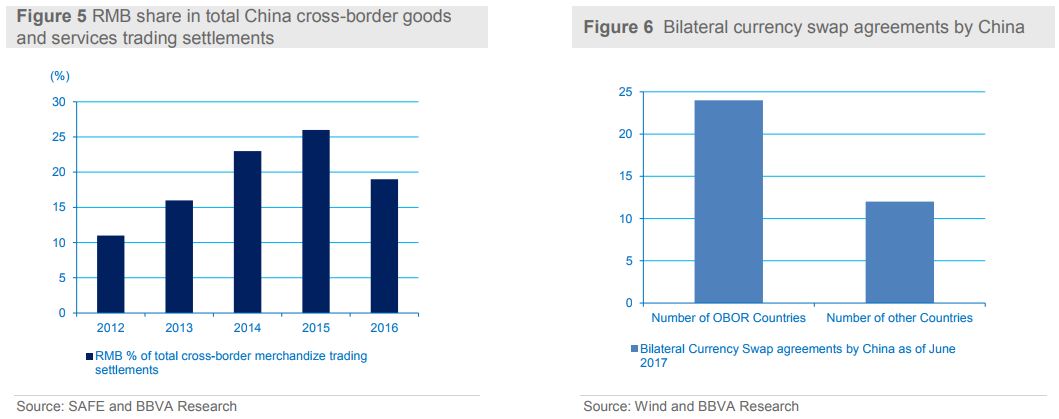

Despite RMB’s inclusion in IMF’s SDR basket in September 2016, prospects of RMB internationalization have taken a hit over the past year as Chinese policymakers tightened capital controls and exercised greater discretion on the daily Yuan fixing aimed at defending the currency against depreciation pressures (Figure – 5). Such capital controls are unlikely to be eased anytime soon given the backdrop of rising global interest rates. However, strong geopolitical and economic linkages achieved through OBOR present ample room for China to expand RMB usage in cross-border trading settlements. The use of RMB in OBOR transactions accounted for about 14% of total cross border trading settlements since 2015, as compared to an average 23% of total RMB trading settlements over the past two years. In addition, China has scope to further expand bilateral local currency swap agreements across OBOR countries. Currently, China has swap agreements with 36 countries (at RMB 3.3 trillion), of which 24 are OBOR countries (Figure– 6).

As per the Asian Development Bank, OBOR countries will need to invest $22.6 tn, or $1.5 tn annually in infrastructure from 2016 to 2030, mainly across electricity generation, transportation and telecommunication sectors. OBOR thus has the potential to deliver infrastructure and in turn higher growth for OBOR countries, particularly where older financial institutions, such as the Asian Development Bank (ADB) in Asia, have fallen short.

Despite having nearly jumped 4-fold to $126 tn by end 2015, the stock Chinese investments as share of total foreign investment stock in OBOR countries is still relatively low at less than 3% when compared to investments by the US (10%) and Europe (50%). Scope to boost Chinese investments is thus huge. The key to plug this gap is for China and the recipient OBOR countries to meet on agreeable terms.

Notwithstanding its long term economic benefits, in the near term, OBOR recipient countries face potential debt sustainability concerns from a pickup in OBOR related inbound investment flows through foreign direct investment and RMB bilateral currency swap agreements. The past three years have seen an increase in indebtedness of OBOR countries, although, so far, the rise in their external debt is much more modest compared to that of domestic debt.

That said, the external debt structure has already seen a shift for economies such as Pakistan, where financing by external non-government entities has risen from 7% of total external debt in 2010 to 14% in 2016. The long gestation period of such investments raises the need for OBOR economies to generate high and sustainable growth for sustaining future debt-servicing capacity. In addition, recipient countries also risk being exposed to less stable and more expensive funding due to increased dependence on Chinese lending while moving away from funding by international financial institutions such as the World Bank and IMF. So far, OBOR funding is mainly reliant on China based institutions. These include Chinese policy banks, China Export and Credit Insurance Corporation, Commercial banks, local financial institutions and local governments. These together have committed around 80% of the total funding (at more than $750 bn) until 2016. The rest includes funds, loan guarantees and grants provided to China by international financial institutions such as the Asia Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), Silk Road fund, New Development Bank for BRICS, Shanghai Cooperation Organization Development Bank, the ADB and World Bank.

OBOR could play a key role in enhancing internationalization of RMB

Despite RMB’s inclusion in IMF’s SDR basket in September 2016, prospects of RMB internationalization have taken a hit over the past year as Chinese policymakers tightened capital controls and exercised greater discretion on the daily Yuan fixing aimed at defending the currency against depreciation pressures (Figure – 5). Such capital controls are unlikely to be eased anytime soon given the backdrop of rising global interest rates. However, strong geopolitical and economic linkages achieved through OBOR present ample room for China to expand RMB usage in cross-border trading settlements. The use of RMB in OBOR transactions accounted for about 14% of total cross border trading settlements since 2015, as compared to an average 23% of total RMB trading settlements over the past two years. In addition, China has scope to further expand bilateral local currency swap agreements across OBOR countries. Currently, China has swap agreements with 36 countries (at RMB 3.3 trillion), of which 24 are OBOR countries (Figure– 6).

Hong Kong plays a key role in developing OBOR

At the 19th Party Congress, President Xi noted that Communist Party will continue to support Hong Kong and Macau in integrating their own development into the overall development of the country. Xi’s commitment underscores Hong Kong’s role as a major OBOR financing hub. As an already established business facilitator between China and rest of the world, Hong Kong has what it takes in its new role within the OBOR framework, namely the rule of law, total capital mobility, currency convertibility, no tax on interest, dividend and capital gains, access to China’s capital markets and, most importantly, the support of Beijing. In this context, policy efforts are underway to interlink Hong Kong’s offering as an international financial centre – venture capital, private equity, IPOs, bond issuances, investment banking, M&A’s and reinsurance – with the Mainland’s Greater Bay Area that includes 11 cities (including Guangzhou and Shenzen) of the Pearl River Delta, known for its modern engineering technologies, hi-tech venture capitalists, start-ups and top research universities. Such integration is bound to have a significant influence on OBOR projects going forward.

The strategic position of Turkey as a passage between Europe and Asia is pivotal for OBOR’s success

For Turkey, which received 2% of total OBOR investments from China between 2013 to 2015, the initiative presents both strategic as well as economic opportunities. OBOR related railroad linkages would facilitate regional interdependence, in turn fostering geopolitical stability between Turkey and its neighbouring countries. The region is marked by militarized and terminally closed borders (e.g. the Turkish-Armenian border). From a power balance perspective, an enhanced role in OBOR would enable Turkey to lead development initiatives across the region, which includes weaker economies such as Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Georgia and Azerbaijan. On the economic front, while China is currently Turkey’s second largest trade partner after Germany, its trade deficit with China has increased notably over the past 5 years to $23 bn in 2016 from $18.5 bn in 2012. OBOR would enable Turkey to establish proper legal infrastructure, lift trade barriers, develop effective cooperation across customs and standards and develop closer participation in trade fairs in China.

Seen as an extension of the OBOR initiative, the 525-mile-Baku-Tbilisi-Kars project will halve the time taken to move goods from China to Turkey. As a part of this project, a railway line connecting Turkey and Azerbaijan was opened last month. Once complete, the route would facilitate transport of EU and Turkey produced food products to China, in turn bypassing Russia’s ban on food imports and transit. Turkey aims to realize “Trans Hazar- Middle Corridor” Project, complementing the North Line from China to Europe and opening a new connecting corridor between China and Europe. To align OBOR with “Middle Corridor” Project of Turkey, a Memorandum of Understanding was signed on 1st of July, 2016 before the G20 Hangzhou Summit. All this would lead to closer and more balanced trade integration with China and other participating countries.

China-Latin America trade and investment links and the role of OBOR

While Latin American (LatAm) countries are currently not members of the OBOR initiative, China’s impact on LatAm’s regional development has been significant over the past decade. The region’s trade growth with China has outstripped that with rest of the world since 2000. Natural resources account for largest share of China’s imports as well as direct investments into LatAm. Its exports to China are mainly characterized by primary products, such as crude oil, iron/steel, copper, solid fuels, scrap aluminium, precious metals, meat etc. With regards Chinese investments, between 2015-2016, LatAm accounted for 14% share in direct investments in energy sector from China while its share in transportation and metals was 8%. However, heavy dependence on commodity exports has made LatAm vulnerable to a slowdown in China’s economic growth and its rebalancing efforts. In this context, LatAm’s involvement in the OBOR initiative can provide several benefits for the region. OBOR's contours have been left flexible by design with investments ranging from infrastructure, to satellite, to sports industry. This presents an opportunity for LatAm to 1) sustain its commodity export demand along OBOR, 2) reduce its commodity dependency, boost productivity and move up the export value chain and 3) increase opportunities for bilateral financing from China.

Closing the gap between China's investment promise and actual implementation

Host country circumstances play an important role in determining the success rate of China's foreign investments along the OBOR. Excluding Singapore, nearly 55% of Chinese OBOR investments since 2013 have taken place in countries with weak economic, fiscal, and institutional strength and a high susceptibility to event risks. Under such circumstances, preferential credit and research subsidies offered by Chinese government to direct investments to OBOR countries may not be enough to overcome investor confidence. OBOR’s strategic and economic objectives can compete with each other, directing Chinese investments into unviable projects driven by political objectives. Politically influenced non-profitable investments by Chinese state-owned enterprises along OBOR further exacerbate its failure rate. Chinese enterprises often follow the political wind in Beijing, such as the OBOR initiative, to secure capital overseas, without a clear investment strategy.

As a key source of funding for OBOR, Chinese financial institutions thus have a credit risk exposure from implementation risks in OBOR countries, which could erode banks’ asset quality and increase contingent liabilities for Chinese government. To address this issue, authorities have tightened controls for outward investments by SOE's, mandating comprehensive and advanced risk assessment. Further, policy efforts to educate and offer a networking platform for Chinese investors, banks and law firms aimed at facilitating OBOR investments have been stepped up. Such efforts, however, would do little to enhance profitability of OBOR projects or enhance their completion rate given that the bottlenecks to investments in such countries are primarily beyond China's control.

All said, OBOR is rapidly expanding in scale, scope and ambition. China has emphasized on open participation and that OBOR is not intended to become a China-led bloc. As such, leaving OBOR less structured and open-ended seems a deliberate attempt by China to tackle international scepticism over China’s global ambitions. As a brain child of President Xi, OBOR will continue to receive strong backing as long as Xi remains in power. 19th Chinese Communist Party Congress almost confirmed him China’s core leader beyond 2022.

Hong Kong plays a key role in developing OBOR

At the 19th Party Congress, President Xi noted that Communist Party will continue to support Hong Kong and Macau in integrating their own development into the overall development of the country. Xi’s commitment underscores Hong Kong’s role as a major OBOR financing hub. As an already established business facilitator between China and rest of the world, Hong Kong has what it takes in its new role within the OBOR framework, namely the rule of law, total capital mobility, currency convertibility, no tax on interest, dividend and capital gains, access to China’s capital markets and, most importantly, the support of Beijing. In this context, policy efforts are underway to interlink Hong Kong’s offering as an international financial centre – venture capital, private equity, IPOs, bond issuances, investment banking, M&A’s and reinsurance – with the Mainland’s Greater Bay Area that includes 11 cities (including Guangzhou and Shenzen) of the Pearl River Delta, known for its modern engineering technologies, hi-tech venture capitalists, start-ups and top research universities. Such integration is bound to have a significant influence on OBOR projects going forward.

The strategic position of Turkey as a passage between Europe and Asia is pivotal for OBOR’s success

For Turkey, which received 2% of total OBOR investments from China between 2013 to 2015, the initiative presents both strategic as well as economic opportunities. OBOR related railroad linkages would facilitate regional interdependence, in turn fostering geopolitical stability between Turkey and its neighbouring countries. The region is marked by militarized and terminally closed borders (e.g. the Turkish-Armenian border). From a power balance perspective, an enhanced role in OBOR would enable Turkey to lead development initiatives across the region, which includes weaker economies such as Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Georgia and Azerbaijan. On the economic front, while China is currently Turkey’s second largest trade partner after Germany, its trade deficit with China has increased notably over the past 5 years to $23 bn in 2016 from $18.5 bn in 2012. OBOR would enable Turkey to establish proper legal infrastructure, lift trade barriers, develop effective cooperation across customs and standards and develop closer participation in trade fairs in China.

Seen as an extension of the OBOR initiative, the 525-mile-Baku-Tbilisi-Kars project will halve the time taken to move goods from China to Turkey. As a part of this project, a railway line connecting Turkey and Azerbaijan was opened last month. Once complete, the route would facilitate transport of EU and Turkey produced food products to China, in turn bypassing Russia’s ban on food imports and transit. Turkey aims to realize “Trans Hazar- Middle Corridor” Project, complementing the North Line from China to Europe and opening a new connecting corridor between China and Europe. To align OBOR with “Middle Corridor” Project of Turkey, a Memorandum of Understanding was signed on 1st of July, 2016 before the G20 Hangzhou Summit. All this would lead to closer and more balanced trade integration with China and other participating countries.

China-Latin America trade and investment links and the role of OBOR

While Latin American (LatAm) countries are currently not members of the OBOR initiative, China’s impact on LatAm’s regional development has been significant over the past decade. The region’s trade growth with China has outstripped that with rest of the world since 2000. Natural resources account for largest share of China’s imports as well as direct investments into LatAm. Its exports to China are mainly characterized by primary products, such as crude oil, iron/steel, copper, solid fuels, scrap aluminium, precious metals, meat etc. With regards Chinese investments, between 2015-2016, LatAm accounted for 14% share in direct investments in energy sector from China while its share in transportation and metals was 8%. However, heavy dependence on commodity exports has made LatAm vulnerable to a slowdown in China’s economic growth and its rebalancing efforts. In this context, LatAm’s involvement in the OBOR initiative can provide several benefits for the region. OBOR's contours have been left flexible by design with investments ranging from infrastructure, to satellite, to sports industry. This presents an opportunity for LatAm to 1) sustain its commodity export demand along OBOR, 2) reduce its commodity dependency, boost productivity and move up the export value chain and 3) increase opportunities for bilateral financing from China.

Closing the gap between China's investment promise and actual implementation

Host country circumstances play an important role in determining the success rate of China's foreign investments along the OBOR. Excluding Singapore, nearly 55% of Chinese OBOR investments since 2013 have taken place in countries with weak economic, fiscal, and institutional strength and a high susceptibility to event risks. Under such circumstances, preferential credit and research subsidies offered by Chinese government to direct investments to OBOR countries may not be enough to overcome investor confidence. OBOR’s strategic and economic objectives can compete with each other, directing Chinese investments into unviable projects driven by political objectives. Politically influenced non-profitable investments by Chinese state-owned enterprises along OBOR further exacerbate its failure rate. Chinese enterprises often follow the political wind in Beijing, such as the OBOR initiative, to secure capital overseas, without a clear investment strategy.

As a key source of funding for OBOR, Chinese financial institutions thus have a credit risk exposure from implementation risks in OBOR countries, which could erode banks’ asset quality and increase contingent liabilities for Chinese government. To address this issue, authorities have tightened controls for outward investments by SOE's, mandating comprehensive and advanced risk assessment. Further, policy efforts to educate and offer a networking platform for Chinese investors, banks and law firms aimed at facilitating OBOR investments have been stepped up. Such efforts, however, would do little to enhance profitability of OBOR projects or enhance their completion rate given that the bottlenecks to investments in such countries are primarily beyond China's control.

All said, OBOR is rapidly expanding in scale, scope and ambition. China has emphasized on open participation and that OBOR is not intended to become a China-led bloc. As such, leaving OBOR less structured and open-ended seems a deliberate attempt by China to tackle international scepticism over China’s global ambitions. As a brain child of President Xi, OBOR will continue to receive strong backing as long as Xi remains in power. 19th Chinese Communist Party Congress almost confirmed him China’s core leader beyond 2022.