Hong Hao: Market Rescue: Will It Work?

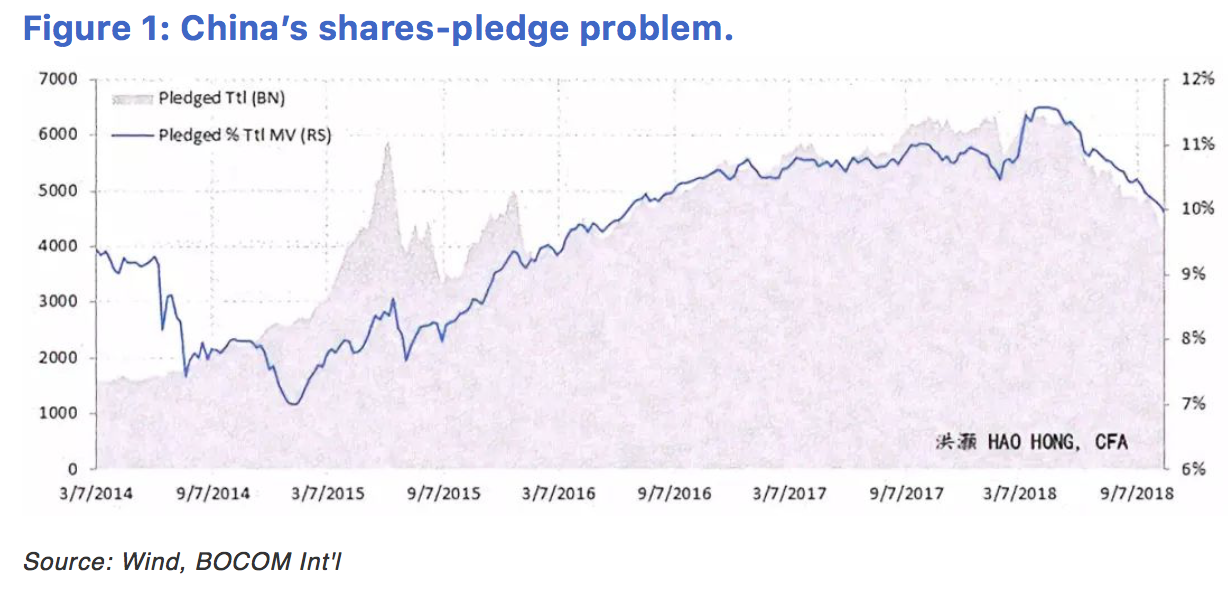

2018-10-30 IMI That said, given that the entire emerging market has been under pressure since late January, and that the percentage of market pledged has been rising in tandem as the market recovered from the 2015 crash, it is unlikely that these share-pledged loans are the reason for the bear market, although it must have aggravated it. Meanwhile, the surging volatility in the US market has not helped – the consequence of the colliding economic down cycle in China and the peaking cycle in the US (“The Colliding Cycles of the US and China”, 20180902).

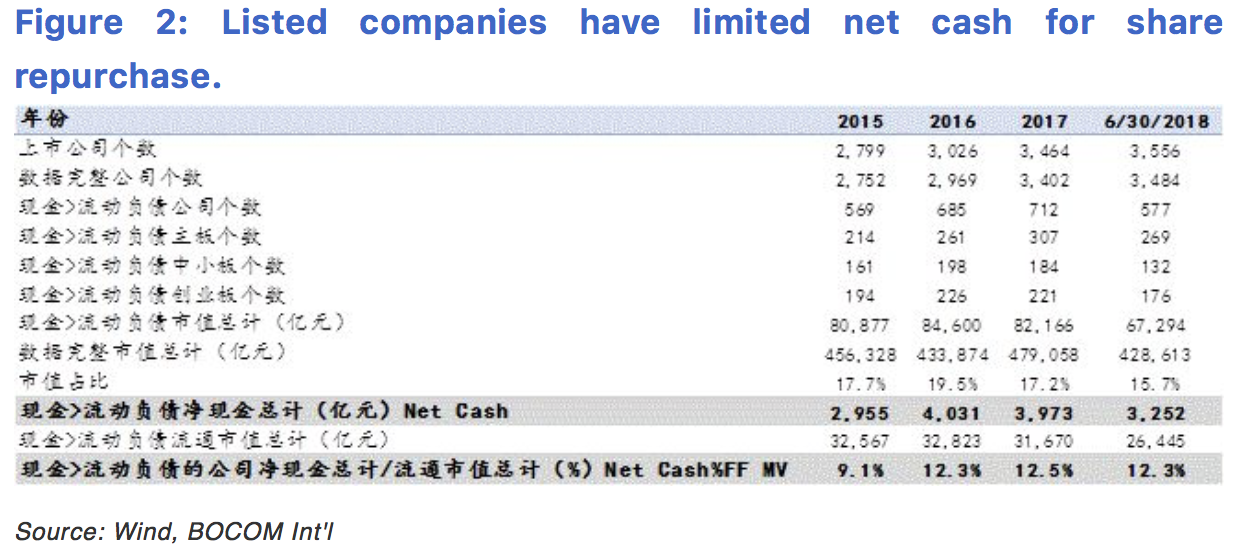

Will the swift changes of corporate law to allow easier share repurchase work? Our analysis suggests the answer is unclear. We compare listed companies’ net cash on balance sheet with their current liabilities. If net cash is positive, the companies will have the ability to buy back shares in the open market. We find that the listed companies only have 325 billion yuan of net cash, or 12.3% of the corresponding companies’ free-float market cap, but less than 1% of the entire market’s capitalization of over 40 trillion yuan. This figure has fallen from just over 400 billion yuan, but the percentage remains stable – a result of a falling market (Figure 2). As such, the net cash that can be deployed for share buyback is limited, despite the change of law. It could help those companies with some excess cash, but these companies are strong in their own right, and thus probably less prone to support their own shares.

That said, given that the entire emerging market has been under pressure since late January, and that the percentage of market pledged has been rising in tandem as the market recovered from the 2015 crash, it is unlikely that these share-pledged loans are the reason for the bear market, although it must have aggravated it. Meanwhile, the surging volatility in the US market has not helped – the consequence of the colliding economic down cycle in China and the peaking cycle in the US (“The Colliding Cycles of the US and China”, 20180902).

Will the swift changes of corporate law to allow easier share repurchase work? Our analysis suggests the answer is unclear. We compare listed companies’ net cash on balance sheet with their current liabilities. If net cash is positive, the companies will have the ability to buy back shares in the open market. We find that the listed companies only have 325 billion yuan of net cash, or 12.3% of the corresponding companies’ free-float market cap, but less than 1% of the entire market’s capitalization of over 40 trillion yuan. This figure has fallen from just over 400 billion yuan, but the percentage remains stable – a result of a falling market (Figure 2). As such, the net cash that can be deployed for share buyback is limited, despite the change of law. It could help those companies with some excess cash, but these companies are strong in their own right, and thus probably less prone to support their own shares.

In sum, these tactics are likely to support the subdued market sentiment. But they have not touched the essence of the issue that the China’s stock market has been confronted with – the stock market has not always been an inclusive pursuit to give the hoi polloi the opportunity to participate in wealth creation via the growth of listed companies. Instead, it has been a game of “rip-off”, of the rich over the poor, the haves over the have-nots, the insiders over the outsiders. And the Chinese retail investors, often in good spirit, nickname such a game “harvesting chives” (because chives grow fast and can be harvested over and over).

In recent history, there have been two great bull runs in the Chinese stock markets – one from mid-2005 to late-2007, and another from mid-2014 to mid-2015. The fundamental reason for these bull markets is that there was structural change prior to the inception of these bull markets - to include retail investors in the pursuit of wealth creation: in 2005, it is the stock ownership reform to resolve the status of the restricted shares held by the state; and in 2014, the significant growth of margin lending, rightly or wrongly, let a great many soar from rags to riches, and then back to earth.

The reason why the Chinese favors property as an asset class over stocks, and property has done exceedingly well is not just because property is the most legitimate way to take on leverage, even for a working class. It is because property is probably the only fair game that has been consistently letting the most number of people participate in wealth creation. It started from the housing reform in 1998, when the state transferred significant wealth to the masses through selling state-owned property titles at a token price.

In our report titled “the Market Bottom: When and Where” more than two years ago (20160604), we re-defined the market bottom as relative to a long-term economic growth rate. We showed that a log-linear relationship between the Shanghai Composite and the implicit GDP growth target implied by China’s Five-Year-Plan since 1986 (Figure 3). Interestingly, the time when Shanghai touched its bottom twice in the past, 2005 and 2014, coincided with the structural changes we discussed above. In this report two years ago, we wrote that the theoretical market bottom should be around 2,450, should the historical relationship persist.

In sum, these tactics are likely to support the subdued market sentiment. But they have not touched the essence of the issue that the China’s stock market has been confronted with – the stock market has not always been an inclusive pursuit to give the hoi polloi the opportunity to participate in wealth creation via the growth of listed companies. Instead, it has been a game of “rip-off”, of the rich over the poor, the haves over the have-nots, the insiders over the outsiders. And the Chinese retail investors, often in good spirit, nickname such a game “harvesting chives” (because chives grow fast and can be harvested over and over).

In recent history, there have been two great bull runs in the Chinese stock markets – one from mid-2005 to late-2007, and another from mid-2014 to mid-2015. The fundamental reason for these bull markets is that there was structural change prior to the inception of these bull markets - to include retail investors in the pursuit of wealth creation: in 2005, it is the stock ownership reform to resolve the status of the restricted shares held by the state; and in 2014, the significant growth of margin lending, rightly or wrongly, let a great many soar from rags to riches, and then back to earth.

The reason why the Chinese favors property as an asset class over stocks, and property has done exceedingly well is not just because property is the most legitimate way to take on leverage, even for a working class. It is because property is probably the only fair game that has been consistently letting the most number of people participate in wealth creation. It started from the housing reform in 1998, when the state transferred significant wealth to the masses through selling state-owned property titles at a token price.

In our report titled “the Market Bottom: When and Where” more than two years ago (20160604), we re-defined the market bottom as relative to a long-term economic growth rate. We showed that a log-linear relationship between the Shanghai Composite and the implicit GDP growth target implied by China’s Five-Year-Plan since 1986 (Figure 3). Interestingly, the time when Shanghai touched its bottom twice in the past, 2005 and 2014, coincided with the structural changes we discussed above. In this report two years ago, we wrote that the theoretical market bottom should be around 2,450, should the historical relationship persist.

On October 19, 2018, the Shanghai Composite plunged to 2,449.197 before it rebounded. In the past two years, we documented a mysterious force that has prevented the Shanghai Composite to arrive at its theoretical bottom, and had presented our findings to top policy makers (Figure 4). Recent public filings showed that the “National Team” had left the market.

On October 19, 2018, the Shanghai Composite plunged to 2,449.197 before it rebounded. In the past two years, we documented a mysterious force that has prevented the Shanghai Composite to arrive at its theoretical bottom, and had presented our findings to top policy makers (Figure 4). Recent public filings showed that the “National Team” had left the market.

After the First Session of the Twelfth National People’s Congress on March 17, 2013, Premier Li Keqiang commented while answering questions from the press: “sometimes stirring vested interests may be more difficult than stirring the soul”. It is a candid and vivid assessment of the challenges that the Chinese market is facing. With the short-term policy tactical maneuvers, the Chinese market will attempt to heal, albeit hampered by overseas volatility. But before we see structural changes that “stir the soul”, the return of the great bull market remains elusive.

After the First Session of the Twelfth National People’s Congress on March 17, 2013, Premier Li Keqiang commented while answering questions from the press: “sometimes stirring vested interests may be more difficult than stirring the soul”. It is a candid and vivid assessment of the challenges that the Chinese market is facing. With the short-term policy tactical maneuvers, the Chinese market will attempt to heal, albeit hampered by overseas volatility. But before we see structural changes that “stir the soul”, the return of the great bull market remains elusive.