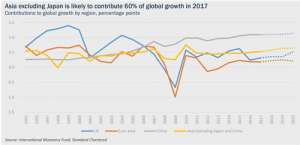

David Mann: Asia to Contribute 60% of Global Growth

2017-03-30 IMI

Economic outlook Markets are wary of the uncertain outlook for private sector investment and trade in the light of Donald Trump’s election. Asia’s economic linkages to the US are much weaker compared with a decade ago, yet remaining linkages may prevent Asian central banks from easing policy in the short term. It will be difficult to diverge from US monetary policy, especially if exchange rates remain as vulnerable as they have been since the 8 November election.

On external trade, there is room for positive surprises in Asia’s 2017 export data because of base and price effects. Last year’s low base should flatter year-on-year export growth in 2017. In addition, a partial recovery in export prices is likely to boost exports in nominal terms. Even with no further price rises, export values are likely to return to growth in 2017. These factors should start to materialise by the second quarter. This is also when emerging market Asian currencies are expected to be at their weakest in response to US reflation, further boosting exports.

China’s growth will remain steady in the run-up to the National Party Congress in late 2017. Many longer-term challenges remain, including excess leverage, overcapacity and the demographic drag that will become more problematic in the 2020s. However, these issues are not expected to reduce growth below the current rate of above 6% ahead of such a politically important event for the Chinese Communist party. This, however, may mean more pain later.

Monetary easing has run its course Monetary easing is over across Asia, mainly because of higher inflation and pressure to avoid divergence with the US. Standard Chartered forecasts project still-sluggish external demand in 2017, and tighter financial conditions due to upward pressure on dollar funding costs and dollar strength. While inflation is likely to rise, it is expected to remain below longer-term averages.

Exchange rates have typically been Asia’s main mechanism of adjustment to higher US rates, and this is expected to be repeated in 2017. The loosening of monetary conditions may therefore happen via the exchange rate channel, rather than policy rate cuts.

India is a significant exception. The shock announcement in early November that it will eliminate 85% of currency in circulation to crack down on the informal economy is causing a cash crunch and hindering economic activity. Expectations for India’s policy rate and GDP growth over the next two years have been adjusted down to reflect the consequences.

Assuming a large portion of the cash in the untaxed economy simply vanishes, this could be worth as much as 2-3% of GDP – a major shock to the system. In this context, the recent public sector salary rise and good monsoon rains are unlikely to be as supportive of growth as originally anticipated. Markets are on the lookout for more surprise announcements.