Dong Jinyue, Betty Huang, Xia Le: Taming China's Shadow Banking Sector

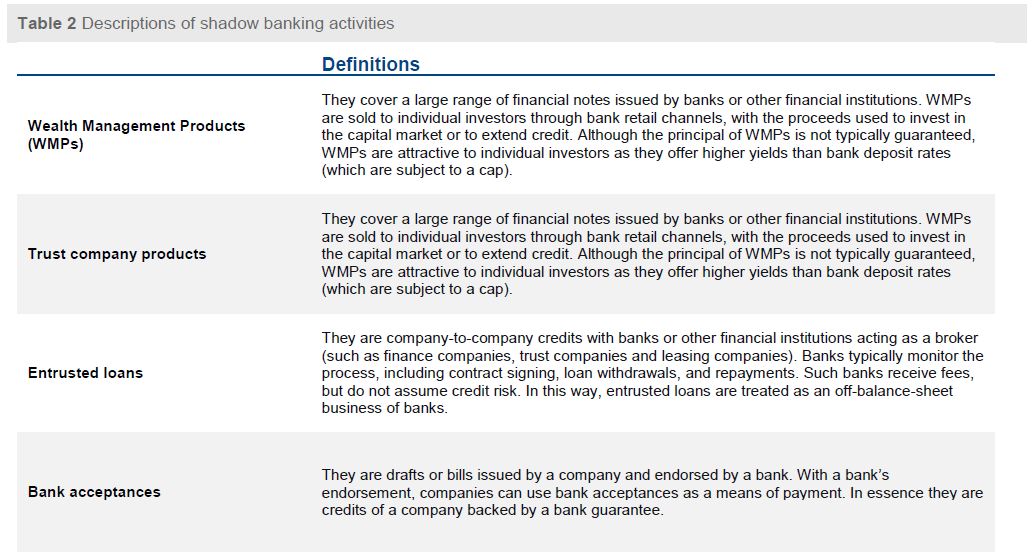

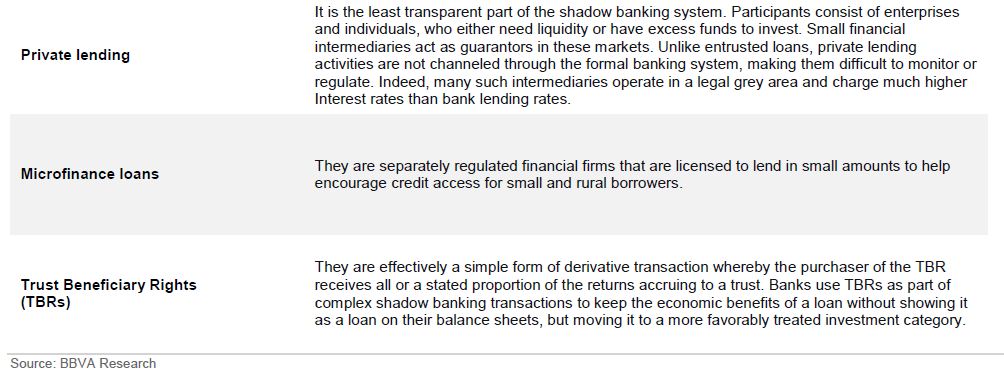

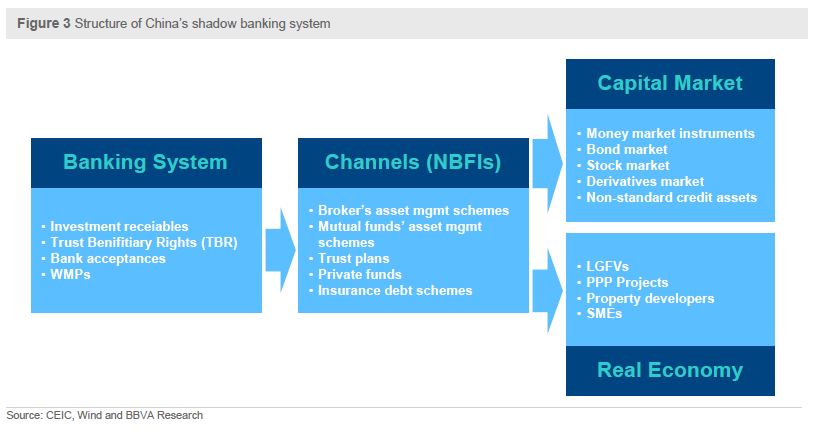

2017-09-12 IMI The financial institutions’ efforts to circumvent regulations have led to a plethora of business models in the shadow banking sector, including: Wealth Management Products (WMPs), trust company products, entrusted loans, bank acceptances, private lending, microfinance loans, Trust Beneficiary Rights (TBRs), etc. (The detailed definitions of these shadow banking activities can be found in Appendix)

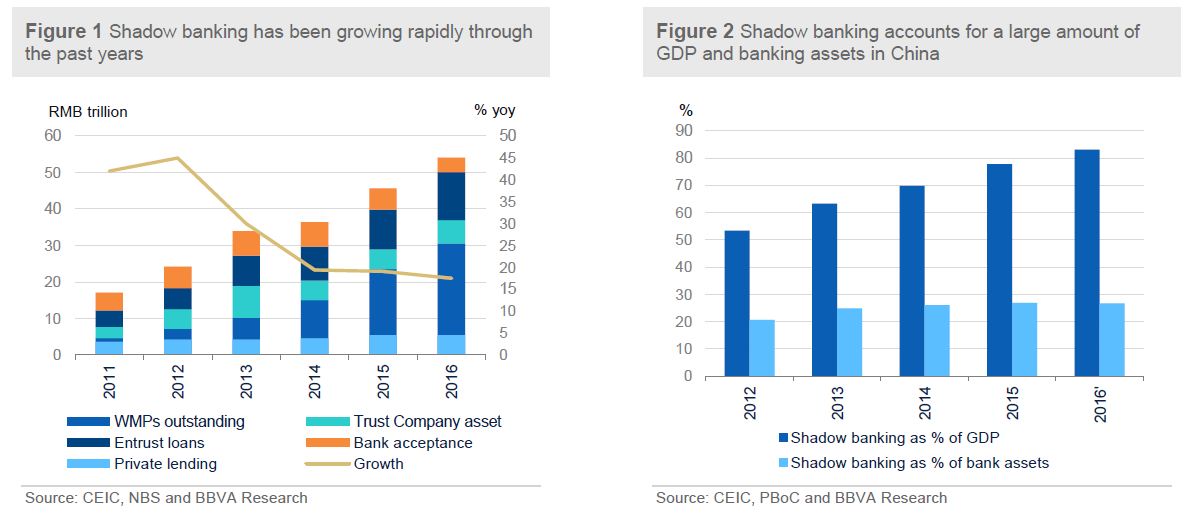

However, the majority of these shadow banking activities are bank-centric in nature. In general, banks partner with non-bank financial institutions (NBFIs) to channel funds that are raised from off-balance-sheet product issuances (forexample, WMPs), to the capital market and (or) the real sector.

Another feature of today’s shadow banking sector is the increasing complexity of the structure as some shadow banking business models tend to intertwine with each other. For example: traditional bank depositors can purchase WMPs for higher investment returns. Then banks invest the proceeds collected from WMPs in other shadow banking products - trust beneficiary right (TBR) or even other WMPs etc. The issuers of TBR and WMPs, which are generally non-banking financial institutions (NBFIs), could either reinvest the funds in capital markets (such as money market,stock, bond or derivatives), or extend loans to the borrowers in the real sector, including property developers, SMEs and local government financial vehicles (LGFVs) etc. (Figure 3) As a result, the bank-centric structure of the shadow banking sector has significantly lengthened the chain of financial intermediation between the depositors and final fund users.

It is also noted that the prosperity of shadow banking activities occurred in the context of China’s financial liberalization. Part of shadow banking activities also functions to boost growth by lowering financing costs for those small-medium-sized-enterprises (SMEs) whose fund demand have long been neglected by the formal banking sector and capital markets. In the meantime, the shadow banking activities also enrich the financial products in the market and provide more available investment vehicles for households to park their ever-increasing savings.

The financial institutions’ efforts to circumvent regulations have led to a plethora of business models in the shadow banking sector, including: Wealth Management Products (WMPs), trust company products, entrusted loans, bank acceptances, private lending, microfinance loans, Trust Beneficiary Rights (TBRs), etc. (The detailed definitions of these shadow banking activities can be found in Appendix)

However, the majority of these shadow banking activities are bank-centric in nature. In general, banks partner with non-bank financial institutions (NBFIs) to channel funds that are raised from off-balance-sheet product issuances (forexample, WMPs), to the capital market and (or) the real sector.

Another feature of today’s shadow banking sector is the increasing complexity of the structure as some shadow banking business models tend to intertwine with each other. For example: traditional bank depositors can purchase WMPs for higher investment returns. Then banks invest the proceeds collected from WMPs in other shadow banking products - trust beneficiary right (TBR) or even other WMPs etc. The issuers of TBR and WMPs, which are generally non-banking financial institutions (NBFIs), could either reinvest the funds in capital markets (such as money market,stock, bond or derivatives), or extend loans to the borrowers in the real sector, including property developers, SMEs and local government financial vehicles (LGFVs) etc. (Figure 3) As a result, the bank-centric structure of the shadow banking sector has significantly lengthened the chain of financial intermediation between the depositors and final fund users.

It is also noted that the prosperity of shadow banking activities occurred in the context of China’s financial liberalization. Part of shadow banking activities also functions to boost growth by lowering financing costs for those small-medium-sized-enterprises (SMEs) whose fund demand have long been neglected by the formal banking sector and capital markets. In the meantime, the shadow banking activities also enrich the financial products in the market and provide more available investment vehicles for households to park their ever-increasing savings.

Risk transmissions of shadow banking in China

The shadow banking system may become a source of systematic risks. In particular, the risks include:

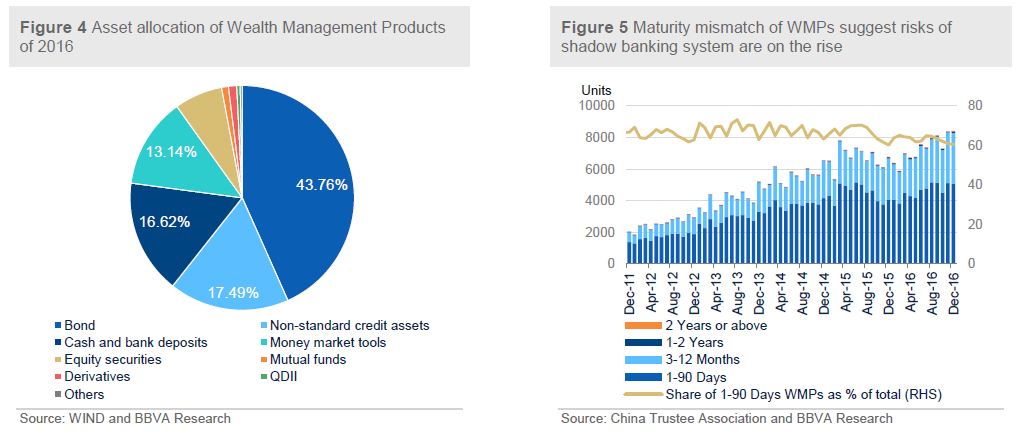

First, the asset quality in the shadow banking system could be problematic. For instance, around 17.5% of WMPs’ underlying assets are “non-standard credit assets” (NSCA), including trust and entrusted loans, bank acceptance etc. (Figure 4) A considerable proportion of underlying assets of trust products go to SMEs and the real estate sector.

These SMEs and real estate developers are more susceptible to business cycle and the change of the government policy, in particular the housing policy which has been frequently changed over the past several years. As a result, the asset quality in the shadow banking system could deteriorate rapidly when macro-environment turns unfavourable.

Worse is the low-quality risk management in the shadow banking sector. Banks tend to devote fewer resources to monitor and manage the risks associated with these off-balance-sheet products while rely on the creditworthiness of NBFIs. Meanwhile, the majority of NBFIs lack the necessary expertise and manpower to manage credit risks of their underlying assets. All in all, the problematic asset quality subjects the shadow banking sector to higher credit risk than that in the formal banking sector.

Second, liquidity risk of shadow banking activities stem from maturity mismatch between the liability and asset sides of shadow banking products. Indeed, most of issued WMPs have a tenor between 1 and 3 months (Figure 6) while their asset side always has much longer maturities. That being said, these underlying projects are subject to serious rollover risks if the credit market condition deteriorates quickly.

Last but not least, the intertwining of the formal and shadow banking sectors further increase the interconnectedness of the entire financial system. As a result, the contagion risk among the financial system has become larger. Moreover, due to the opaqueness of the shadow banking sector, it is increasingly difficult for financial institutions to identify the risk source and manage their counterparty risks. A single product default in the shadow banking sector could be easily amplified to a strong shockwave through the entire financial system.

Risk transmissions of shadow banking in China

The shadow banking system may become a source of systematic risks. In particular, the risks include:

First, the asset quality in the shadow banking system could be problematic. For instance, around 17.5% of WMPs’ underlying assets are “non-standard credit assets” (NSCA), including trust and entrusted loans, bank acceptance etc. (Figure 4) A considerable proportion of underlying assets of trust products go to SMEs and the real estate sector.

These SMEs and real estate developers are more susceptible to business cycle and the change of the government policy, in particular the housing policy which has been frequently changed over the past several years. As a result, the asset quality in the shadow banking system could deteriorate rapidly when macro-environment turns unfavourable.

Worse is the low-quality risk management in the shadow banking sector. Banks tend to devote fewer resources to monitor and manage the risks associated with these off-balance-sheet products while rely on the creditworthiness of NBFIs. Meanwhile, the majority of NBFIs lack the necessary expertise and manpower to manage credit risks of their underlying assets. All in all, the problematic asset quality subjects the shadow banking sector to higher credit risk than that in the formal banking sector.

Second, liquidity risk of shadow banking activities stem from maturity mismatch between the liability and asset sides of shadow banking products. Indeed, most of issued WMPs have a tenor between 1 and 3 months (Figure 6) while their asset side always has much longer maturities. That being said, these underlying projects are subject to serious rollover risks if the credit market condition deteriorates quickly.

Last but not least, the intertwining of the formal and shadow banking sectors further increase the interconnectedness of the entire financial system. As a result, the contagion risk among the financial system has become larger. Moreover, due to the opaqueness of the shadow banking sector, it is increasingly difficult for financial institutions to identify the risk source and manage their counterparty risks. A single product default in the shadow banking sector could be easily amplified to a strong shockwave through the entire financial system.

New approach to curb the shadow banking

The authorities started their clampdown on shadow banking activities a few years ago. However, regulators seem to have been outwitted by financial institutions insofar as the size of the shadow banking sector continues to swell. We reckon that unsuccessful efforts to curb the shadow banking sector were handicapped by a couple of factors. First, the authorities’ tightening efforts have to give way to the pressure of meeting growth target from time to time.Second, many forms of shadow banking activities have already extended to different areas of financial system while different regulators cannot make concerted efforts to regulate.

The authorities have realized the problem and started to apply a comprehensive approach to tackle shadow banking activities. Since December 2016 a number of financial regulators, including the CBRC (banking regulator), CSRC (security market regulator) and CIRC (insurance regulator), have stepped up their efforts to curb shadow banking activities in a more coordinated way.

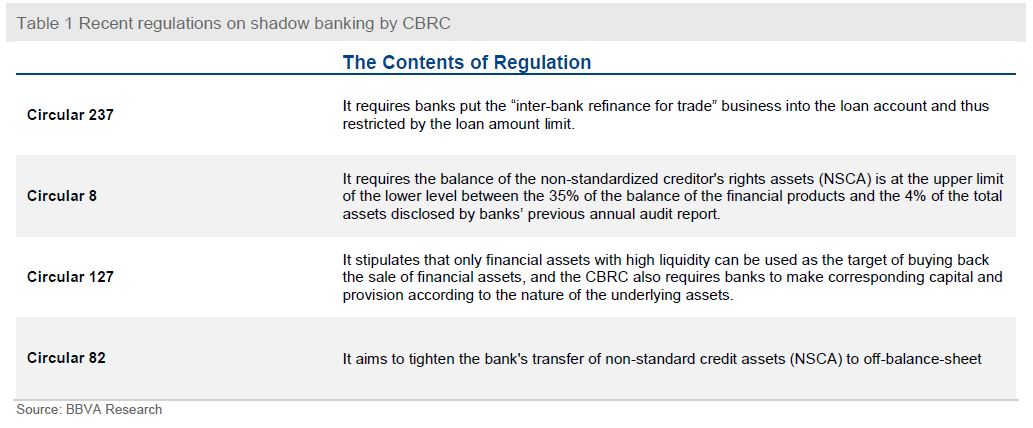

Meanwhile, the PBoC also shifted their monetary policy stance to “prudent” and has implemented a new regulatory framework of Macro Prudential Assessment (MPA), the thrust of which is to force banks to include many previously off-balance-sheet activities into their books. (Table 1)

More importantly, the National Financial Work Conference, which was concluded in July, announced that the authorities will establish a high-level financial regulatory commit to lead and coordinate different regulators in addressing financial vulnerabilities, chief among which is the shadow banking sector. The Conference also clarified that the PBOC will take the leading role in implementing the macro-prudential policy and is held account for maintaining financial stability.

New approach to curb the shadow banking

The authorities started their clampdown on shadow banking activities a few years ago. However, regulators seem to have been outwitted by financial institutions insofar as the size of the shadow banking sector continues to swell. We reckon that unsuccessful efforts to curb the shadow banking sector were handicapped by a couple of factors. First, the authorities’ tightening efforts have to give way to the pressure of meeting growth target from time to time.Second, many forms of shadow banking activities have already extended to different areas of financial system while different regulators cannot make concerted efforts to regulate.

The authorities have realized the problem and started to apply a comprehensive approach to tackle shadow banking activities. Since December 2016 a number of financial regulators, including the CBRC (banking regulator), CSRC (security market regulator) and CIRC (insurance regulator), have stepped up their efforts to curb shadow banking activities in a more coordinated way.

Meanwhile, the PBoC also shifted their monetary policy stance to “prudent” and has implemented a new regulatory framework of Macro Prudential Assessment (MPA), the thrust of which is to force banks to include many previously off-balance-sheet activities into their books. (Table 1)

More importantly, the National Financial Work Conference, which was concluded in July, announced that the authorities will establish a high-level financial regulatory commit to lead and coordinate different regulators in addressing financial vulnerabilities, chief among which is the shadow banking sector. The Conference also clarified that the PBOC will take the leading role in implementing the macro-prudential policy and is held account for maintaining financial stability.

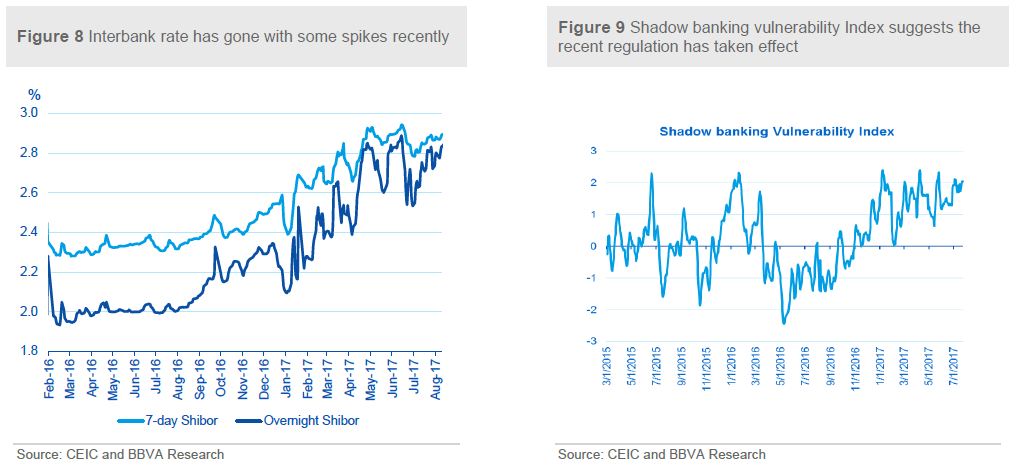

The combination of recent monetary prudence stance and concerted regulatory efforts has already started to take effects. Some shadow banking activities such as trust loans, entrusted loans and banks acceptance have significantly slowed recently. (Figure 6) Meanwhile, the new issuance of interbank CDs, which are used to finance small banks’ shadow banking activities, has also shrunk significantly. (Figure 7) The interbank rate has also had some spikes recently. (Figure 8) Altogether, our BBVA shadow banking vulnerability index, based on the Big Data analysis, indicates the recent shadow banking activities have been moderated due to the authorities’ regulation measures.(Figure 9)

How regulation tightening will affect growth?

In view of the shadow banking’s role in servicing the real economy, we attempt to gauge to what extent the ongoing clampdown on shadow banking will drag on growth. The clampdown of the shadow banking sector can directly lead to the change of money and credit supply. For instance, M2 growth dipped to the historical low to 9.2% YoY in July, the historical low for the past 20 years, due to the clampdown of the shadow banking activities. As such, we believe that the impact of shadow banking activities on the real economy effects through the money and credit supply change.

Our benchmark Vector Autoregression (VAR) model, which includes China’s M2 growth, GDP growth and CPI as endogenous variables as we use M2 growth slowdown to indicate the current regulation tightening and financial deleveraging, shows that a decrease of 1% in M2 growth leads to 0.16% slowdown in GDP. The second experiment is to change M2 growth into Total Social Financing (TSF), a broad gauge of total credit capturing both regular bank loans and shadow banking activities. (The PBOC provides TSF from 2002 onwards, in recognition that banks ceased to be the only finance sources that mattered and it became necessary to examine a full range of financial activity.) The results indicate that 1% decrease in TSF leads to 0.1% slowdown in GDP, in line with our first experiment’s results.

The combination of recent monetary prudence stance and concerted regulatory efforts has already started to take effects. Some shadow banking activities such as trust loans, entrusted loans and banks acceptance have significantly slowed recently. (Figure 6) Meanwhile, the new issuance of interbank CDs, which are used to finance small banks’ shadow banking activities, has also shrunk significantly. (Figure 7) The interbank rate has also had some spikes recently. (Figure 8) Altogether, our BBVA shadow banking vulnerability index, based on the Big Data analysis, indicates the recent shadow banking activities have been moderated due to the authorities’ regulation measures.(Figure 9)

How regulation tightening will affect growth?

In view of the shadow banking’s role in servicing the real economy, we attempt to gauge to what extent the ongoing clampdown on shadow banking will drag on growth. The clampdown of the shadow banking sector can directly lead to the change of money and credit supply. For instance, M2 growth dipped to the historical low to 9.2% YoY in July, the historical low for the past 20 years, due to the clampdown of the shadow banking activities. As such, we believe that the impact of shadow banking activities on the real economy effects through the money and credit supply change.

Our benchmark Vector Autoregression (VAR) model, which includes China’s M2 growth, GDP growth and CPI as endogenous variables as we use M2 growth slowdown to indicate the current regulation tightening and financial deleveraging, shows that a decrease of 1% in M2 growth leads to 0.16% slowdown in GDP. The second experiment is to change M2 growth into Total Social Financing (TSF), a broad gauge of total credit capturing both regular bank loans and shadow banking activities. (The PBOC provides TSF from 2002 onwards, in recognition that banks ceased to be the only finance sources that mattered and it became necessary to examine a full range of financial activity.) The results indicate that 1% decrease in TSF leads to 0.1% slowdown in GDP, in line with our first experiment’s results.

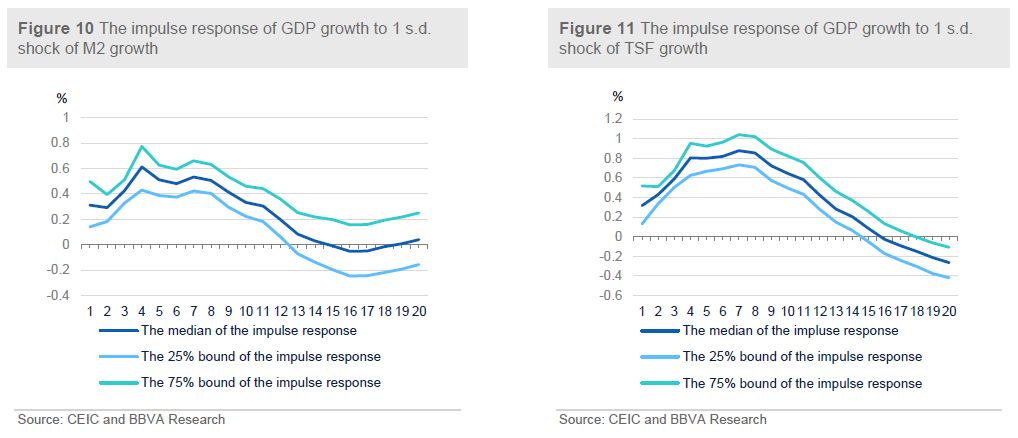

In addition, Figure 10 and 11 show the impulse responses of GDP growth corresponding to one standard deviation shock to M2 growth and to TSF growth. Both impulse responses indicate that one standard deviation positive shock of M2 or TSF leads to around 0.3% increase of GDP growth increasing, and it reaches the maximum response after around 4 periods (4 months) for M2 growth shock and around 7 periods (7 months) for TSF shock. Thus from the perspective of shock response and shock persistency, it shows that the currently regulation tightening will have downward impact on growth but to a limited extent.

On balance, the progress of China’s on-going regulation on shadow banking could last for a couple of years. We therefore believe that it will have a modest but persistently downward pressure on growth in the coming years. However, these efforts to address shadow banking activities are imperative and valuable in the long run given that they will largely diminish the hard-landing risk of the economy and financial system.

Appendix

In addition, Figure 10 and 11 show the impulse responses of GDP growth corresponding to one standard deviation shock to M2 growth and to TSF growth. Both impulse responses indicate that one standard deviation positive shock of M2 or TSF leads to around 0.3% increase of GDP growth increasing, and it reaches the maximum response after around 4 periods (4 months) for M2 growth shock and around 7 periods (7 months) for TSF shock. Thus from the perspective of shock response and shock persistency, it shows that the currently regulation tightening will have downward impact on growth but to a limited extent.

On balance, the progress of China’s on-going regulation on shadow banking could last for a couple of years. We therefore believe that it will have a modest but persistently downward pressure on growth in the coming years. However, these efforts to address shadow banking activities are imperative and valuable in the long run given that they will largely diminish the hard-landing risk of the economy and financial system.

Appendix