Javier Guzmán Calafell: Why a Multicurrency System Is Stronger

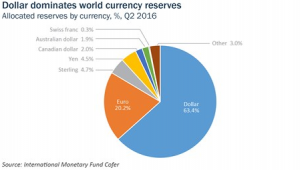

2017-03-30 IMI The predominance of a handful of currencies appears incompatible with developments in the world economy. Emerging market economies account for nearly 60% of world GDP. Growth rates are expected to remain significantly higher than in advanced economies. It therefore seems reasonable to expect emerging market currencies to play a more important role in the composition of international reserve assets.

The economic size of an issuing country is only one determinant of a currency’s internationalisation. An economy’s role in trade networks, macroeconomic and financial stability, the liquidity and openness of national markets, and the stability and convertibility of its currency are also major contributing factors.

Among emerging market currencies, the renminbi appears most likely to secure a significant role. This is partly in view of China’s position in the world economy, but also because of the Chinese authorities’ interest in renminbi internationalisation.

This has been illustrated by the gradual opening of Chinese financial markets to foreign participation, the renminbi´s inclusion in the IMF’s special drawing

right basket, and China’s negotiation of currency swap agreements. However, China is still far from meeting all of the conditions to provide the renminbi with international status.

The race to consolidate the renminbi as a global currency should be viewed as a long-term endeavour. Moreover, the question remains whether a monetary system with more international currencies would be stronger than the present one. I believe it would be.

A sound and efficient system

The more economies with macroeconomic and financial stability which are open to trade and have liquid capital markets, the more the system as a whole will be sound and efficient. A greater number of international currencies entails greater possibilities to diversify overall portfolio risk. A multicurrency reserve system may reduce the risk of persistent overvaluation of assets, including exchange rates.

Countries’ role as reserve issuers will also gain a more evenly distributed range of benefits, such as seigniorage gains and lower interest rates on debt, as well as a reduced risk of major and persistent global external imbalances.

Nevertheless, a multicurrency reserve system is not free from difficulties, as the case of renminbi internationalisation illustrates. The process requires a comprehensive opening of China’s financial markets to foreign transactions, as well as a floating exchange rate. Such moves may have unintended consequences for both the domestic economy and the global financial system. Financial and exchange rate liberalisation in other countries may be accompanied by periods of turbulence.

Irrespective of the challenges of a transition towards international status, the risks of sudden portfolio shifts and exchange rate volatility will not disappear under a multicurrency reserve system. Such a system may lead to greater short-term capital flow volatility and exchange rate adjustments as a result of the increased substitutability of currencies. Currency internationalisation may give rise to other risks, such as reduced control over monetary aggregates.

Notwithstanding these challenges, the benefits of a wider availability of global currencies should outweigh the potential costs in the long term.

The predominance of a handful of currencies appears incompatible with developments in the world economy. Emerging market economies account for nearly 60% of world GDP. Growth rates are expected to remain significantly higher than in advanced economies. It therefore seems reasonable to expect emerging market currencies to play a more important role in the composition of international reserve assets.

The economic size of an issuing country is only one determinant of a currency’s internationalisation. An economy’s role in trade networks, macroeconomic and financial stability, the liquidity and openness of national markets, and the stability and convertibility of its currency are also major contributing factors.

Among emerging market currencies, the renminbi appears most likely to secure a significant role. This is partly in view of China’s position in the world economy, but also because of the Chinese authorities’ interest in renminbi internationalisation.

This has been illustrated by the gradual opening of Chinese financial markets to foreign participation, the renminbi´s inclusion in the IMF’s special drawing

right basket, and China’s negotiation of currency swap agreements. However, China is still far from meeting all of the conditions to provide the renminbi with international status.

The race to consolidate the renminbi as a global currency should be viewed as a long-term endeavour. Moreover, the question remains whether a monetary system with more international currencies would be stronger than the present one. I believe it would be.

A sound and efficient system

The more economies with macroeconomic and financial stability which are open to trade and have liquid capital markets, the more the system as a whole will be sound and efficient. A greater number of international currencies entails greater possibilities to diversify overall portfolio risk. A multicurrency reserve system may reduce the risk of persistent overvaluation of assets, including exchange rates.

Countries’ role as reserve issuers will also gain a more evenly distributed range of benefits, such as seigniorage gains and lower interest rates on debt, as well as a reduced risk of major and persistent global external imbalances.

Nevertheless, a multicurrency reserve system is not free from difficulties, as the case of renminbi internationalisation illustrates. The process requires a comprehensive opening of China’s financial markets to foreign transactions, as well as a floating exchange rate. Such moves may have unintended consequences for both the domestic economy and the global financial system. Financial and exchange rate liberalisation in other countries may be accompanied by periods of turbulence.

Irrespective of the challenges of a transition towards international status, the risks of sudden portfolio shifts and exchange rate volatility will not disappear under a multicurrency reserve system. Such a system may lead to greater short-term capital flow volatility and exchange rate adjustments as a result of the increased substitutability of currencies. Currency internationalisation may give rise to other risks, such as reduced control over monetary aggregates.

Notwithstanding these challenges, the benefits of a wider availability of global currencies should outweigh the potential costs in the long term.