Il Houng Lee: A Commentary on the Economic Strategy Discussed at the 2022 NPC and CPPCC Sessions

2022-06-02 IMIIl Houng Lee, Member of IMI International Committee; Former Member of Monetary Policy Board, Bank of Korea; Senior Associate Researcher, Vesalius College (CSDS Center)

A brief description of current economic challenges faced by China is presented first to provide a context in which to assess the “policy framework” discussed in the Two Sessions. The focus of this commentary is not on short-term policy measures but on the adequacy of the overall strategy to steer the economy towards a sustainable medium-term growth.

Overview of current challenges: Common global factors

A common global challenge can be summarized as the declining growth trend and high (youth) unemployment. One reason for the declining trend growth can be attributed to weakening “consumption-production-income” cycle. Industrial concentration, increasing high-tech capital intensity of production, and labor skill mismatch, may have led income to be less widely distributed among market participants, thereby weakening the link from income to consumption. Increasing synchronization of consumer demand for global standardized products that are more efficiently produced by multinational companies, including through managing complex modularized global value chain, have outpriced local competitors. As a result, producers catering for local markets, usually self-employed or SMEs who account for a large share of employment but a small share in value added, are losing ground. Only those able to find a niche market through highly localized services or specific technology remain.

Associated social cost such as from widening income and wealth inequality, high (youth) unemployment, and deteriorating climate conditions are rising. Wealth and income inequality worsens due to the widening gap between those with and without financial and/or physical assets, those belonging to the main global production league and those unable to access or remain in the market, and those with skills and experience (educated) and those lacking experience (youth) or with outdated skills (aged). The pandemic has further exacerbated this widening gap. Natural capital, the stock of natural assets such as the eco-system, uncontaminated soil, clean air and water, is being eroded by not internalizing negative externalities, e.g., carbon emissions, into production cost.

Macroeconomic policies, which are instruments to stabilize short-term price and output volatility, have been used extensively along with strengthened social welfare system to contain the rising social cost. However, as structural transformation through market response takes time, the cost of prolonged use of macroeconomic policies is now beginning to outweigh the benefit. Moreover, the widening financing gap of social welfare system is expected to worsen with aging. The upshot of all this is the accumulation of debt, which in turn acts as a further drag on GDP growth. Debt in a broader sense includes public debt,[1] overvalued asset prices (defined as prices above the net present value of return/income of the assets),[2] and excessive leverage relative to GDP (those associated with non-performing assets).[3] Demand for leveraged investment in financial assets and properties continues to rise due to the lack of alternative investment opportunities and the far larger return from valuations gains. Accommodative monetary policy, i.e., a very low or negative interest rate is neutralizing the burden on the economy,[4] keeps ailing firms afloat, and are encouraging leverage. On the fiscal side, large transfer payments are required to maintain social welfare and unemployment low.

Overview of current challenges: China specific factors

China shares many of these features noted above as it is at the center of global value chain. The country’s specific challenges arise mainly from the rapid pace of economic growth. The public sector, through the State-owned Enterprises (SOEs), government-led investment, and state-intervention in resource allocation (especially in heavy industries), has been an important driver in transforming a low- to a middle-income country. Despite the successes,[5] signs of strains are emerging as effective state intervention become difficult with increasing sophistication of the economic system.

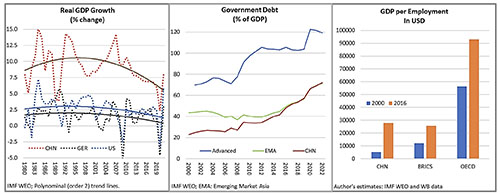

[Figure 1]

These strains arise from excessive (local) government investment and SOEs, especially since they play an important role in providing employment and countering cyclical downturns. The high investment share of GDP in China is largely attributed to the state which accounts for more than 50% of total investment. This compares with about 15% in both the US and Germany. As such, marginal product of capital (or the inverse of ICOR) is falling while public debt is rising. The situation differs from other countries where strains arise from supporting consumption either directly as social transfers and government expenditure, or indirectly through the financial sector and then absorbing the losses ex-post.

Gradual reduction in investment is necessary to engineer a smooth transition to a consumption-based and sustainable growth. GDP per employment in US dollars has risen from $5,140 to about $27,580 between 2000 and 2016. This is a 5.4-fold increase and compares with the average increase in BRICS of 2.1, and 1.6 among the OECD countries. Consumption-based growth would imply a lower investment share of GDP. This transition cannot take place, however, through faster consumption growth for practical reasons—it has already recorded the highest growth of 10% per annum during the last 40 years in US dollar terms[6] than any other country. While it is true that household savings ratio in China is higher than those of its peers,[7] a falling savings rate can better be achieved through lower investment growth. Progress in the currently envisaged reforms could support substituting the impact of lower investment on household income with other sources of growth.

Relating to the desirability of the larger role of the state, there are two aspects to consider before concluding whether it is necessarily associated with suboptimal resource allocation. The first is to weigh the benefit of SOEs contributing more directly to employment creation and acting as a buffer of short-term output volatility as against crowding out the private sector. Anecdotal evidence of SOEs’ role as semi-social protection mechanism can perhaps be seen from the surge of SOE defaults since the onset of Covid-19 in 2020.[8] Yet, private sector corporations have not necessarily performed better given the high default rates before the pandemic, especially in the property market. The second is to weigh the benefit of relying on relative price adjustments (i.e., the visible hand) as against administrative intervention of market price adjustments (i.e., invisible hand).[9]

Irrespective of the size of the state, a more pertinent question would thus be whether the state can ensure a stable and a level playing field by quickly adjusting the regulatory framework and keep up with, even stay ahead of, the rapidly evolving technological and financial developments. In this regards, bold steps have been taken to reign in on big tech companies’ modus operandi to protect consumer welfare, data and payment system security, and competition.[10]

Yet, the state accounts for almost 60% of total capital stock, as compared with 30% and 20% in the US and Germany, respectively, and entails about a two-fold higher depreciation rate[11] (i.e., China vis-a-vis the average of the US and Germany). This raises the question as to whether the cost of maintaining high public investment is now beginning to outweigh the benefit.

Key strategies of the policy framework of the Two Sessions

The 2020 GDP growth target of 5½ % indicates a realistic and practical policy objective that aims to moderate the recent decline in growth momentum rather than to proactively lift growth to the pre-pandemic level. The job target of 11 million in urban areas suggests further absorption of rural labor (given the lack of jobs and lower productivity) into cities for industry and services. Greater support will be provided for enterprises that expand employment and training. While the overall fiscal policy position does not seem to be expansionary,[12] tax incentives are largely targeted towards small businesses, low-profit enterprises and the self-employed. Export credit insurance for international trade-related SMEs will be expanded. These are consistent with the government efforts to promote SME innovations and startups[13]

The government sees infrastructure investment as a central instrument, including by the local government, to boost provincial economies. The financing of the latter will include, in addition to central government transfers, the use of special-purpose bonds but with an overall cap. Foreign investors are invited to high-end manufacturing and to participate in R&D and in digital services. Medical care and housing for the aged will be expanded partly through attracting private investment. On environment, carbon emission will peak in 2030 and reach neutrality by 2060, i.e., no more depletion of natural capital thereafter.

Further progress is envisaged in regulatory reforms to strengthen fair market competition and enhance SOE efficiency through the implementation of the three-year action plan. Limiting credit growth (social financing) to nominal economic growth will also help to ensure that the financial market remains engaged with the real sector (i.e., avoid decoupling), limiting leveraged investment leading to financial and physical asset price bubbles (containing growth of debt). It would also be important to keep the real interest rate consistent with the targeted liquidity growth and hence with market fundamentals.

Assessment of the policy framework against the challenges

The policy framework of the Two Sessions provides the necessary package to address the key challenges noted above and to steer the economy in the right direction over the medium term. The package includes finding new sources of growth through innovation in technology (including through FDI), support labor to access the product and service market through promoting startups, supporting self-employment, and SME financing, and establish a sound regulatory framework to promote competition and underpin a level playing field for all participants.

The policy framework should help rebuild a virtuous consumption-production-income cycle. A better targeted government spending will also lead to a broader distribution of income among all market participants such as startups and SMEs, rather than as profit of well-established companies. Government support, including through education, to help labor become more innovative, creative, and better tailored to local taste, would further enable everyone to gain better market access through developing new items that can compete with global products.

If a virtuous cycle can be attained and new sources of household income be generated, China will be able to continue to improve its living standard at its current pace and still create jobs with much less investment. Under such a scenario, GDP growth would also be lower as it no longer relies on inefficient investments and the associated buildup of debt. For example, reducing the share of investment to GDP from 45% to 30% over a period of 10 years through reducing public investment while keeping consumption growth constant at 7 % per annum (constant price and national currency base) would imply an overall GDP growth of 4.5%. Overall investment would need to grow only by 0.3% per annum, i.e., holding it almost constant in level terms, while substituting public investment by private investment. This rebalancing would also be consistent with the aim of attaining employment and personal income growth in line with economic expansion and a reduction in energy-intensive activities.

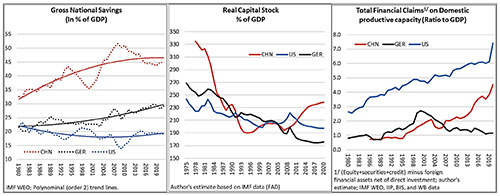

[Figure 2]

Deadweight loss, i.e., debt stock,[14] will also be curtailed under the rebalancing. China’s real capital stock as % of GDP has fallen rapidly through the 1970s-90s and moved in par with those in advanced economies during the 1990s-2000s. This can be explained by the rapid growth in GDP (the denominator) through efficient investment such that the capital stock (the numerator) as a ratio to GDP remained low. However, since the global financial crisis, this ratio has begun to rise again implying a decline in capital efficiency, now reaching the levels recorded in the early 1980s. Moreover, since investment is increasingly financed by leverage, rather than savings, total financial claims on domestic productive capacity as ratio to GDP[15] is rising very fast (i.e., excessive leverage to GDP), well surpassing that of Germany.[16] Moderating public investment and improving private investment efficiency should contain further growth in China’s deadweight.[17]

Relating to regulatory environment, in addition to decisive steps taken to ensure orderly private sector activities, similar progress will be needed in the ongoing efforts to assure leveling the playing field between the SOEs/local government and the private sector. A few examples would be full price flexibility, ensuring premiums that reflect proper risk assessment including through no implicit guarantees, and no regulatory bias or forbearance. Costs arising from optimizing social welfare (instead of profit) by SOEs should be transparently recorded as fiscal expenses which will also help strengthen the governance of SOEs.

Ending remarks

The weakening of the consumption-production-income cycle has led to lower growth and social challenges. Most advanced and emerging economies have responded with expansionary macroeconomic policies. However, given the slow pace of transformation, adverse consequences of the prolonged use of macroeconomic policies are taking a toll in terms of rising debt. Unless proactively addressed, market will correct itself through higher inflation or an abrupt adjustment in asset prices and defaults—none of which are desirable.

China is no exception. The consequence of excessive use of public investment has begun to show up in falling capital inefficiency as well as in rising financial claims already well in excess of its productive capacity. The policy framework of the Two Sessions seems to contain the right strategy to steer the economy towards a sustainable medium-term growth. However, a faster adjustment of state investment and SOEs could curtail the buildup of deadweight and ensure a sustainable medium-term growth.

[1] Even before the pandemic, OECD average general government debt rose from 50% to 85% of GDP during 2007-2019 (to some extent to absorb financial liabilities accumulated prior to the global financial crisis), with Japan, US, and Italy, for example, rising by 60 ppt, 50 ppt, and 44 ppt, respectively (OECD data).

[2] Market capitalization of OECD rose to 147% of GDP (compared with the last peak 110% of GDP before the crash at the GFC), and as for the world total, it rose from 114% of GDP (last peak) to 134% of GDP (World Bank data). Housing prices (2015=100) in OECD rose from 106 (last peak) to 129 in 2020, and for the US, from 119 to 141. Even the Euro Area recorded a significant increase from 119 to 123 during the same period.

[3] See “Redefining Liquidity for Monetary Policy” I.H. Lee, K.H. Kim, and W. Shim, East Asian Economic Review Vol 22 No 3, Sep 2018.

[4] In several countries, interest coverage ratios remained high and debt service ratio low largely due to low interest rates. Inflation, the main objective for monetary policy, is not discussed here.

[5] For example, underpinned by strong public sector led investment, Malaysia maintained rapid economic growth for 23 years (starting in 1974), Indonesia for 27 years (1970), Thailand for 32 years (1965) and Korea for 34 years (1963). China was on its 42nd year (1978) when it faced the pandemic in 2020. During this period, poverty ratio at $1.9 a day (WB data) in China fell from 66.3% in 1990 to 0.5% by 2016.

[6] This compares with consumption growth of 4.5% in G7, 7.0% and 4.4% EM Europe and EM Latin America, respectively, all in US dollar terms (used for comparability).

[7] China’s High Savings: Drivers, Prospects, and Policies; Zhang et al, IMF Working Paper WP/18/277, Dec 2018.

[8] The People’s Republic of China, 2021 Article I Consultation, IMF Country Report (p20).

[9] http://www.news.cn/english/20220324/ed4d0ba14c15446bb9360e985a5ec632/c.html

[10] https://techmonitor.ai/policy/big-tech/chinese-tech-regulation-alibaba-ant-group-tencent

[11] Author’s own assessment based on “Investment and Capital Stock Dataset, 1960-2013” by Fiscal Affairs Department, IMF.

[12] Author’s own assessment based on the People’s Republic of China, 2021 Article IV Consultation, IMF Country Report as the baseline.

[13] E.g., China’s Working Group for Promotion of SME Development in 2000, the State Council executive meeting chaired by Premier Li Keqiang on July 12 to further enhance the support for innovation and entrepreneurship, and the announcement of support for digitalization in 2020.

[14] See footnote 11.

[15] Further adjustment was made to total financial claims relative to that in footnote 3. It is defined as the sum of shares, securities, and loans and then netting out domestic residents’ claims of financial assets abroad (using IIP data). Since total financial claims is the amount a country will ultimately need to repay with goods and services, it is used as a proxy for measuring total productive capacity. This measure as a ratio to GDP should remain stable in the long run (e.g., Germany’s case).

[16] The ratio in China is still lower than that of the US, but caution is needed for a simple comparison since the US is the global center of the financial market.

[17] China’s Path to Consumer-Based Growth: How to Identify and Reduce Excessive Investment, I. H. Lee, M. Syed and L. Xueyan, IMF Working Paper 13/83. Mar 2013