Betty Huang and Xia Le: Early Fruits of Corporate Deleveraging Add to Growth Resilience

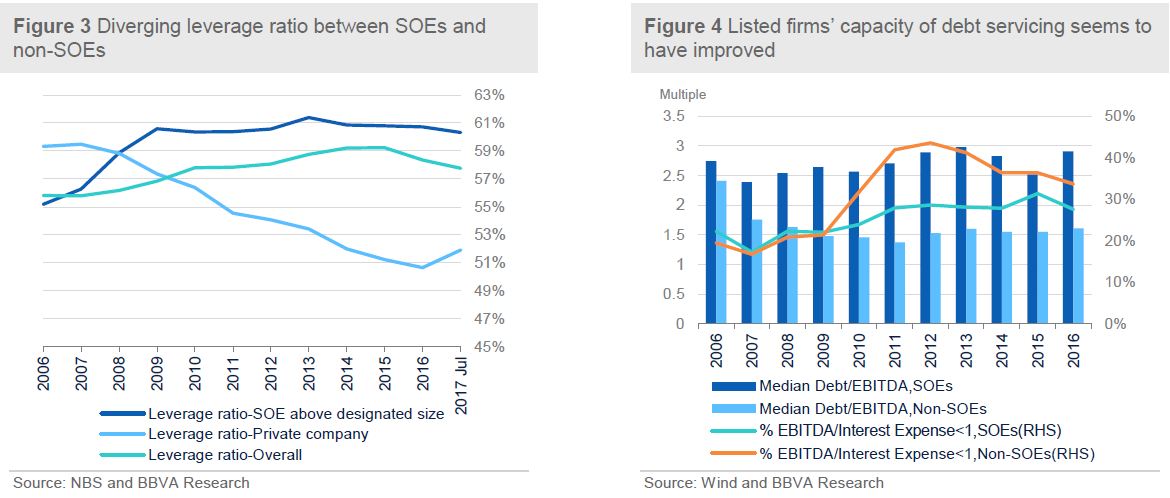

2017-10-09 IMI Encouragingly, some firm-level financial indicators have shown early signals of improvement in firms’ debt problem in particular for those non-SOEs. For example, the leverage ratio of Chinese companies, which is defined as the ratio of firms’ total liabilities to their total assets, has slightly declined since 2014. (Figure 3) Such a trend is even more pronounced for non-SOEs, which have been painstakingly lowering their leverage ratio over the past decade. It is only recently that non-SOEs start to raise the leverage ratio again in tandem with the strong economic recovery.

Similar evidence could be found on listed firms. Based on the information contained in their financial statements, we construct two indicators to measure their indebtedness. One is the ratio of Debt-to-EBITDA, which is a proxy of a firm’s debt level relative to its cash flow. The other is the ratio of EBITDA-to-Interest Expense, which could measure a firm’s capacity to service its interest-bearing debt. A natural threshold of this ratio is 1. A firm with its ratio of EBITDA-to-Interest Expense below could have difficulty in servicing its debt.

We in particular distinguish listed SOEs and non-SOEs in calculating their ratios. (Figure 4) It is noted that the median of Debt-to-EBITDA ratio among all listed non-SOEs didn’t change much over the past decade while the median of SOEs rose in 2016 from the previous year. Listed non-SOEs seemed to have a better record of limiting their debt level. More importantly, the share of listed firms with an EBITDA-to-Interest Expense ratio below 1 decreased in 2016, for both SOEs and non-SOEs, pointing to a general improvement in listed firms’ capacity of debt servicing.

Before drawing any conclusion from the above evidence, we need to understand the discrepancy between the macro indicator (Credit-to-GDP ratio) and those firm-level indicators. We suspect that the rampant shadow banking activities have led to a bifurcating trend between macro and firm-level indicators. As detailed in our thematic note “Taming China's shadow banking”, the shadow banking sector has significantly lengthened the chain of financial intermediation between the depositors and final fund users. A loan could pass through the hands of several middlemen before it reached its final user. As a consequence, the aggregate credit figure is inflated relative to GDP.

Encouragingly, some firm-level financial indicators have shown early signals of improvement in firms’ debt problem in particular for those non-SOEs. For example, the leverage ratio of Chinese companies, which is defined as the ratio of firms’ total liabilities to their total assets, has slightly declined since 2014. (Figure 3) Such a trend is even more pronounced for non-SOEs, which have been painstakingly lowering their leverage ratio over the past decade. It is only recently that non-SOEs start to raise the leverage ratio again in tandem with the strong economic recovery.

Similar evidence could be found on listed firms. Based on the information contained in their financial statements, we construct two indicators to measure their indebtedness. One is the ratio of Debt-to-EBITDA, which is a proxy of a firm’s debt level relative to its cash flow. The other is the ratio of EBITDA-to-Interest Expense, which could measure a firm’s capacity to service its interest-bearing debt. A natural threshold of this ratio is 1. A firm with its ratio of EBITDA-to-Interest Expense below could have difficulty in servicing its debt.

We in particular distinguish listed SOEs and non-SOEs in calculating their ratios. (Figure 4) It is noted that the median of Debt-to-EBITDA ratio among all listed non-SOEs didn’t change much over the past decade while the median of SOEs rose in 2016 from the previous year. Listed non-SOEs seemed to have a better record of limiting their debt level. More importantly, the share of listed firms with an EBITDA-to-Interest Expense ratio below 1 decreased in 2016, for both SOEs and non-SOEs, pointing to a general improvement in listed firms’ capacity of debt servicing.

Before drawing any conclusion from the above evidence, we need to understand the discrepancy between the macro indicator (Credit-to-GDP ratio) and those firm-level indicators. We suspect that the rampant shadow banking activities have led to a bifurcating trend between macro and firm-level indicators. As detailed in our thematic note “Taming China's shadow banking”, the shadow banking sector has significantly lengthened the chain of financial intermediation between the depositors and final fund users. A loan could pass through the hands of several middlemen before it reached its final user. As a consequence, the aggregate credit figure is inflated relative to GDP.

How have Chinese firms managed to reduce their leverage?

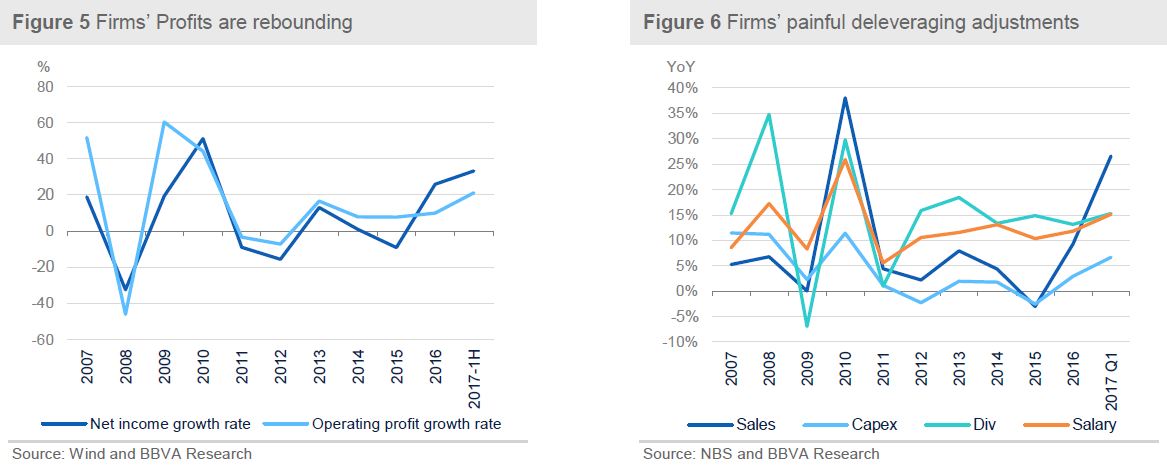

Some people attribute the lower leverage ratio to the authorities’ recent supply-side reform, which is featured by the government-led elimination of overcapacity in some sectors such as iron & steel as well as coal, and its resultant profit pickup of firms (Figure 5). Indeed, non-SOEs’ self-efforts to correcting their debt problem started long before the current wave of profit pickup and their influence is much broader in terms of sector coverage. In our last year’s note“Private Investment Slowdown Marks the Start of China's Long-awaited Deleveraging” we point out that a firm has to go through painful but necessary adjustment if it wants to reduce overburdened debt and restore financial healthiness. These painful efforts include (i) hold up their investment, (ii) cut dividend payment to their shareholders and (iii) shed jobs on a large scale. China’s listed firms have been through all these. (Figure 6)

How have Chinese firms managed to reduce their leverage?

Some people attribute the lower leverage ratio to the authorities’ recent supply-side reform, which is featured by the government-led elimination of overcapacity in some sectors such as iron & steel as well as coal, and its resultant profit pickup of firms (Figure 5). Indeed, non-SOEs’ self-efforts to correcting their debt problem started long before the current wave of profit pickup and their influence is much broader in terms of sector coverage. In our last year’s note“Private Investment Slowdown Marks the Start of China's Long-awaited Deleveraging” we point out that a firm has to go through painful but necessary adjustment if it wants to reduce overburdened debt and restore financial healthiness. These painful efforts include (i) hold up their investment, (ii) cut dividend payment to their shareholders and (iii) shed jobs on a large scale. China’s listed firms have been through all these. (Figure 6)

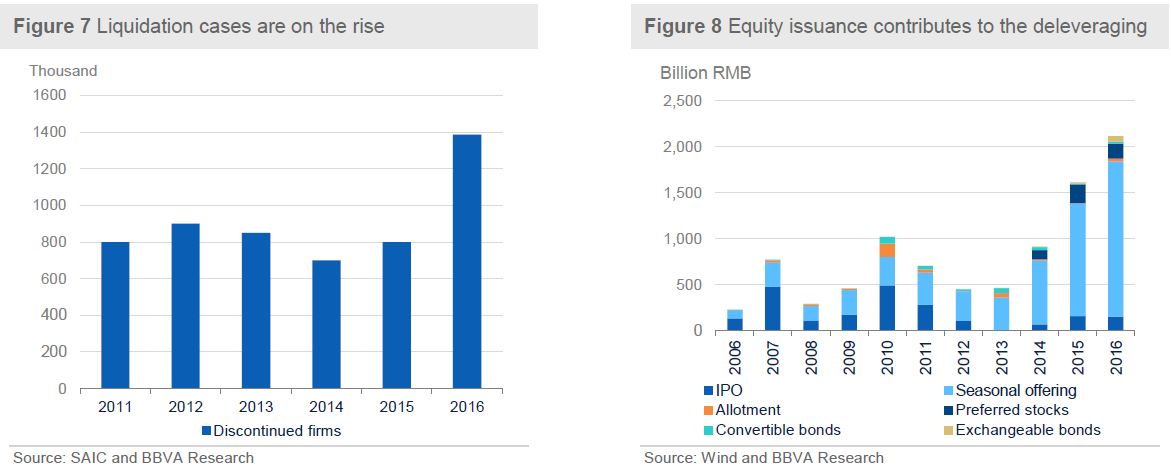

Apparently, not every firm is able to survive through such a process, which has led to an increasing number of liquidation cases of non-SOEs over the past several years. (Figure 7) To a certain degree, it also contributes to the deleveraging of the corporate sector as liquidation could eliminate “bad” debt in the economy.

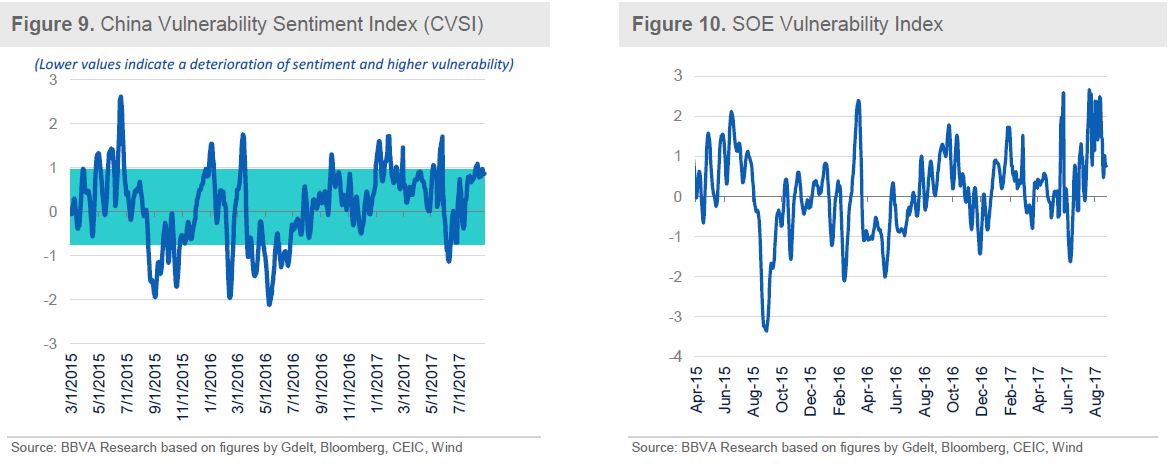

There are other approaches to facilitate firms’ deleveraging. For those listed firms, their efforts of deleveraging can also benefit from additional capital replenishment. (Figure 8) The authorities also introduced the bond-to-equity swap (DES) program in 2016 to alleviate debt burden of distressed SOEs. However the size of this program (to date RMB 776 billion) and its influence remain limited thus far.

Apparently, not every firm is able to survive through such a process, which has led to an increasing number of liquidation cases of non-SOEs over the past several years. (Figure 7) To a certain degree, it also contributes to the deleveraging of the corporate sector as liquidation could eliminate “bad” debt in the economy.

There are other approaches to facilitate firms’ deleveraging. For those listed firms, their efforts of deleveraging can also benefit from additional capital replenishment. (Figure 8) The authorities also introduced the bond-to-equity swap (DES) program in 2016 to alleviate debt burden of distressed SOEs. However the size of this program (to date RMB 776 billion) and its influence remain limited thus far.

The battle field for corporate deleveraging is among SOEs

Despite the relatively better performance of non-SOEs in reducing their leverage, the leverage of SOEs remains at a worrying high level. On average, the leverage of SOEs exceeds 60%, approximately 10 ppts higher than their non-SOE peers. We also find that the average leverage ratio of an industry tends to have a positive relation with the proportion of government ownership in the industry.

The high debt level of SOEs stems from the “soft budget” problem. It was prevalent in many emerging economies where the government plays a pivotal role in economic development and favours national champions. Many Chinese SOEs, although suffering losses of consecutive years, are still able to borrow from banks or the shadow banking sector thanks to the implicit guarantees provided by the central or local governments. As a consequence, many SOEs have become typical zombie companies which maintain unproductive operation by snowballing colossal debt that can no longer be paid.

The authorities have become aware of the adverse consequence of the “soft budget” and set out to address it. In 2016, the government successfully cleaned up 4,977 zombie companies, involving total assets of RMB 412 billion. More importantly, at the once-in-five-year national financial working conference, President Xi Jinping pledged to put the task of deleveraging SOEs on the top of its reform agenda along with tackling China’s shadow banking sector.

Looking ahead, the authorities are likely to reduce SOEs’ leverage by gradually withdrawing the implicit guarantees for them and eliminating zombie companies. Regarding large-size SOEs, the authorities prefer pushing forward more M&As between SOEs to directly liquidating them on concerns of causing massive unemployment. Such a process should proceed with the overall SOE reforms which aim to improve their corporate governance and enhance their efficiency. The authorities might have not been ready to press ahead with massive privatization program yet. Instead, the authorities plan to diversify the ownership of SOEs by introducing private minor investors, namely “mixed ownership reform”. Such efforts could help to further reduce the leverage ratio of these SOEs as new investors will inject capital into these target SOEs.

Moreover, the on-going efforts to curb shadow banking activities will be crucial to containing SOEs’ leverage in terms of cutting off funding channels in grey areas. As far as we know, the shadow banking sector has become one of important funding channels to zombie SOEs since their asset quality has made most of banks reluctant to lend even with the governments’ guarantees. The authorities have indicated that the monetary prudence and regulatory tightening will remain in place until the shadow banking activities are being tamed. In this respect, the authorities’ efforts have already born some early fruits as evidenced by the improved market sentiments towards China’s vulnerabilities. (The methods of constructing these indicators can be referred to our working paper: “Tracking Chinese Vulnerability in Real Time Using Big Data”)

The battle field for corporate deleveraging is among SOEs

Despite the relatively better performance of non-SOEs in reducing their leverage, the leverage of SOEs remains at a worrying high level. On average, the leverage of SOEs exceeds 60%, approximately 10 ppts higher than their non-SOE peers. We also find that the average leverage ratio of an industry tends to have a positive relation with the proportion of government ownership in the industry.

The high debt level of SOEs stems from the “soft budget” problem. It was prevalent in many emerging economies where the government plays a pivotal role in economic development and favours national champions. Many Chinese SOEs, although suffering losses of consecutive years, are still able to borrow from banks or the shadow banking sector thanks to the implicit guarantees provided by the central or local governments. As a consequence, many SOEs have become typical zombie companies which maintain unproductive operation by snowballing colossal debt that can no longer be paid.

The authorities have become aware of the adverse consequence of the “soft budget” and set out to address it. In 2016, the government successfully cleaned up 4,977 zombie companies, involving total assets of RMB 412 billion. More importantly, at the once-in-five-year national financial working conference, President Xi Jinping pledged to put the task of deleveraging SOEs on the top of its reform agenda along with tackling China’s shadow banking sector.

Looking ahead, the authorities are likely to reduce SOEs’ leverage by gradually withdrawing the implicit guarantees for them and eliminating zombie companies. Regarding large-size SOEs, the authorities prefer pushing forward more M&As between SOEs to directly liquidating them on concerns of causing massive unemployment. Such a process should proceed with the overall SOE reforms which aim to improve their corporate governance and enhance their efficiency. The authorities might have not been ready to press ahead with massive privatization program yet. Instead, the authorities plan to diversify the ownership of SOEs by introducing private minor investors, namely “mixed ownership reform”. Such efforts could help to further reduce the leverage ratio of these SOEs as new investors will inject capital into these target SOEs.

Moreover, the on-going efforts to curb shadow banking activities will be crucial to containing SOEs’ leverage in terms of cutting off funding channels in grey areas. As far as we know, the shadow banking sector has become one of important funding channels to zombie SOEs since their asset quality has made most of banks reluctant to lend even with the governments’ guarantees. The authorities have indicated that the monetary prudence and regulatory tightening will remain in place until the shadow banking activities are being tamed. In this respect, the authorities’ efforts have already born some early fruits as evidenced by the improved market sentiments towards China’s vulnerabilities. (The methods of constructing these indicators can be referred to our working paper: “Tracking Chinese Vulnerability in Real Time Using Big Data”)

Implications for China’s growth

The progress of corporate deleveraging has important implications for China’s growth. As shown in the previous section, the deleveraging of non-SOEs seems to come to a halt after several years of painful balance sheet adjustment. In the first half of the year, some non-SOEs even intentionally increase their leverage in a bid to increase investment and expand their production. In the meantime, although the deleveraging of SOEs significantly lags behind their non-SOEs peers, the authorities are now gearing up to accelerate this process as their policy priority has shifted to maintain financial stability.

All in all, the progress of corporate deleveraging has reinforced our confidence in China’s economic outlook. It partially explained why the on-going economic recovery in China has showed better-than-expected strength and sustainability. Although the combination of regulatory tightening and monetary prudence is set to moderate the economy in the coming months, the relative healthy situation of firms’ balance sheets, in particular for non-SOEs, will make the economy more resilient to the cyclical adjustment and external shocks. It also helps to diminish the tail risk of hard-landing and provide more policy room for the authorities to push ahead important structural reforms.

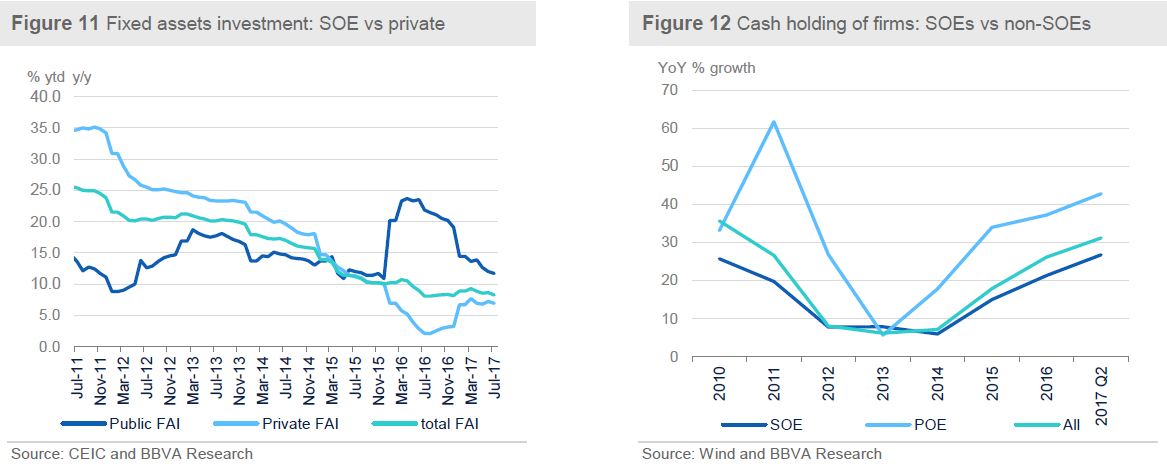

Such a benign scenario is subject to two caveats. First, complacency could sow the seeds of failure. Some early success could make the authorities slow their pace and even avoid painful but necessary reforms. As such, the process of deleveraging and reforming SOEs could be adversely postponed. Second, if non-SOEs don’t have confidence in long-term growth prospect, the deleveraging process among non-SOEs could prompt them to increase their cash hoarding while avoid making new investments. (Figure 11 and 12) As such, the economy could fall in a trap of “balance sheet recession”, in which even firms with good profitability decline to expand their production capacity while use their proceeds to pay off their debt. Collectively, such behaviours could lead to diminished investment demand and years of economic sluggishness as we seen in the past two decades in Japan.

Implications for China’s growth

The progress of corporate deleveraging has important implications for China’s growth. As shown in the previous section, the deleveraging of non-SOEs seems to come to a halt after several years of painful balance sheet adjustment. In the first half of the year, some non-SOEs even intentionally increase their leverage in a bid to increase investment and expand their production. In the meantime, although the deleveraging of SOEs significantly lags behind their non-SOEs peers, the authorities are now gearing up to accelerate this process as their policy priority has shifted to maintain financial stability.

All in all, the progress of corporate deleveraging has reinforced our confidence in China’s economic outlook. It partially explained why the on-going economic recovery in China has showed better-than-expected strength and sustainability. Although the combination of regulatory tightening and monetary prudence is set to moderate the economy in the coming months, the relative healthy situation of firms’ balance sheets, in particular for non-SOEs, will make the economy more resilient to the cyclical adjustment and external shocks. It also helps to diminish the tail risk of hard-landing and provide more policy room for the authorities to push ahead important structural reforms.

Such a benign scenario is subject to two caveats. First, complacency could sow the seeds of failure. Some early success could make the authorities slow their pace and even avoid painful but necessary reforms. As such, the process of deleveraging and reforming SOEs could be adversely postponed. Second, if non-SOEs don’t have confidence in long-term growth prospect, the deleveraging process among non-SOEs could prompt them to increase their cash hoarding while avoid making new investments. (Figure 11 and 12) As such, the economy could fall in a trap of “balance sheet recession”, in which even firms with good profitability decline to expand their production capacity while use their proceeds to pay off their debt. Collectively, such behaviours could lead to diminished investment demand and years of economic sluggishness as we seen in the past two decades in Japan.