Hong Hao: The Year of the Dog——Lessons from 2017

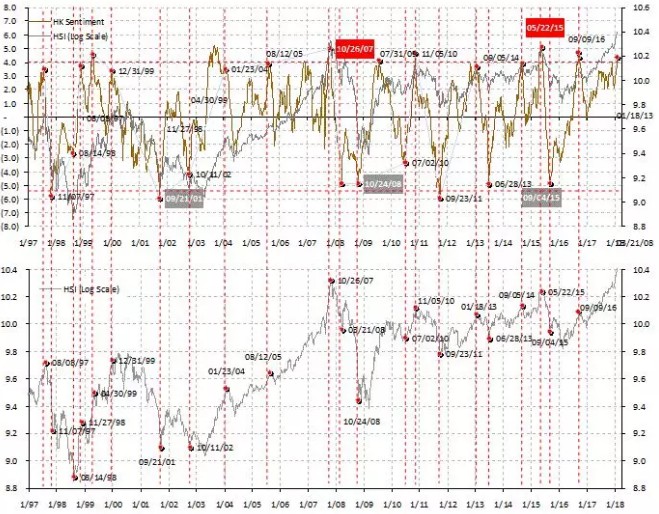

2018-02-13 IMI While we think economic outlook remains sound, market sentiment at such extremely elated level suggests near-term caution for traders. We need to reassess when to rebuild positions after the short-term market excess dissipates.

Non-Consensus Views

Chinese small caps are on a long-term rising trend. 2017 is the first time in more than a decade when large caps rose while small caps fell. The underperformance of small caps has been so extreme and extended that most have relinquished hopes. In our outlook report titled “View from the Peak” on December 4, 2017, we highlighted small caps, as measured by the CSI500 Small-Cap index, should come back after a dismal year as one of our contrarian calls. Since our report, the stretched strength in the A-share big caps has deafened even the most accommodative ears.

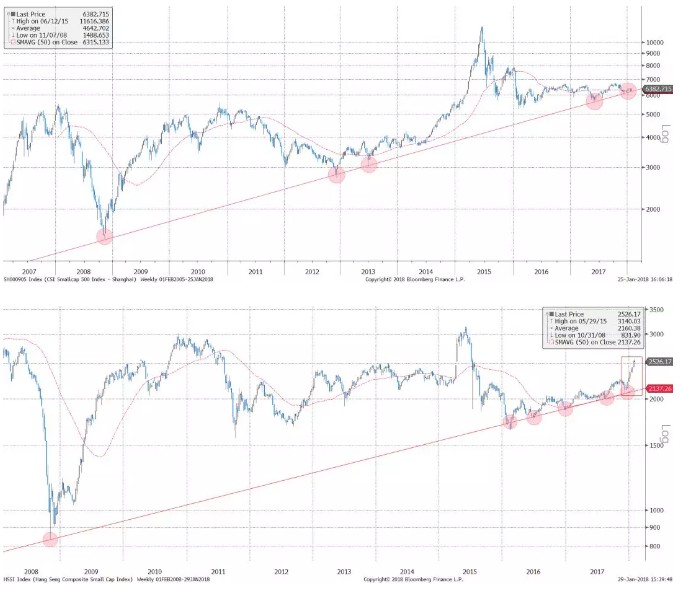

Exhibit 2: The long-term rising trend line of mainland/HK small caps. HK small caps have started to surge (lower panel).

While we think economic outlook remains sound, market sentiment at such extremely elated level suggests near-term caution for traders. We need to reassess when to rebuild positions after the short-term market excess dissipates.

Non-Consensus Views

Chinese small caps are on a long-term rising trend. 2017 is the first time in more than a decade when large caps rose while small caps fell. The underperformance of small caps has been so extreme and extended that most have relinquished hopes. In our outlook report titled “View from the Peak” on December 4, 2017, we highlighted small caps, as measured by the CSI500 Small-Cap index, should come back after a dismal year as one of our contrarian calls. Since our report, the stretched strength in the A-share big caps has deafened even the most accommodative ears.

Exhibit 2: The long-term rising trend line of mainland/HK small caps. HK small caps have started to surge (lower panel).

But the Hong Kong small caps have started to surge since our report (Exhibit 2). They have indeed outperformed the Hong Kong big caps as denoted by the Hang Seng Index. The A-share small caps have also risen. Although they have failed to outperform the big caps, they continue to bounce off their rising long-term trend line. Their valuation is perching on the long-term trend line as well (Exhibit 3). The divergence of performance between A-share and Hong Kong small caps suggests entrenched biased consensus in the domestic A-share market. It will take time for the domestic market to come to terms with our contrarian view.

Exhibit 3: The valuation of China small caps is perching on a rising long-term trend line.

But the Hong Kong small caps have started to surge since our report (Exhibit 2). They have indeed outperformed the Hong Kong big caps as denoted by the Hang Seng Index. The A-share small caps have also risen. Although they have failed to outperform the big caps, they continue to bounce off their rising long-term trend line. Their valuation is perching on the long-term trend line as well (Exhibit 3). The divergence of performance between A-share and Hong Kong small caps suggests entrenched biased consensus in the domestic A-share market. It will take time for the domestic market to come to terms with our contrarian view.

Exhibit 3: The valuation of China small caps is perching on a rising long-term trend line.

Small caps’ earning quality is just as good as that of large caps; value investing has never worked in China. Many equate buying big caps as value investing, and hail the outperformance of big caps in 2017 as the return of value investing.

Exhibit 4: A-share small caps’ earnings quality is as good as that of other larger-cap indices.

Small caps’ earning quality is just as good as that of large caps; value investing has never worked in China. Many equate buying big caps as value investing, and hail the outperformance of big caps in 2017 as the return of value investing.

Exhibit 4: A-share small caps’ earnings quality is as good as that of other larger-cap indices.

Since the inception of the CSI500 Small-Cap index in 2005, its cumulative performance of has been more than two to three times of that of the SSE50 A50 Big-Cap index. Further, after taking out banks and other capex-intensive industries, CSI500’s quality of earnings, as measured by the ratio of Operating Cash Flow to Net Profits (OCF/NP), tracks that of SSE50 very closely. And there is no discernable statistical difference (Exhibit 4). And the average market cap of the CSI500 index companies is around ~RMB 16bn, as compared with ~RMB 14bn of the SSE380 index companies, a.k.a. the "emerging blue chips".

In short, the quality of earnings, the cumulative return over the years and the market caps of the CSI500 index companies are just as good as, or at times even better than those of the SSE50 index companies.

Since the inception of the CSI500 Small-Cap index in 2005, its cumulative performance of has been more than two to three times of that of the SSE50 A50 Big-Cap index. Further, after taking out banks and other capex-intensive industries, CSI500’s quality of earnings, as measured by the ratio of Operating Cash Flow to Net Profits (OCF/NP), tracks that of SSE50 very closely. And there is no discernable statistical difference (Exhibit 4). And the average market cap of the CSI500 index companies is around ~RMB 16bn, as compared with ~RMB 14bn of the SSE380 index companies, a.k.a. the "emerging blue chips".

In short, the quality of earnings, the cumulative return over the years and the market caps of the CSI500 index companies are just as good as, or at times even better than those of the SSE50 index companies.

There is also a school of thoughts that believe big caps should be bought for their “liquidity premium”. We believe that these pundits have confused trading volume with liquidity, which should be defined at the time of crisis. When the chance of a crisis is still low due to the regulators resolve to ward off systemic risks, the regime to value stocks on liquidity is off. We also note that assets with liquidity tend to be sold off during crisis to raise cash, and thus will suffer even more, as seen in the Mexican plunge during the Argentina Crisis in the early 90’s. Be careful what you wish for.

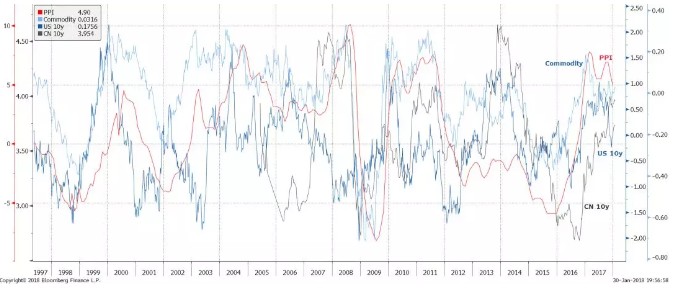

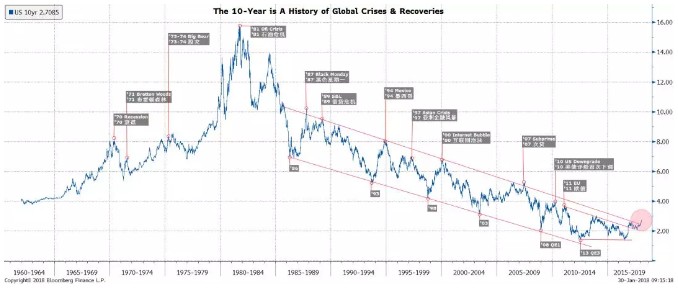

Inflation or not, bond yields are difficult to decline for now because of tightening regulation. The outlook on growth seems to have reached consensus: Chinese growth will likely moderate, and growth outside China, especially in the US, will likely remain strong. As such, the growth outlook is likely to have been priced in. There is a chance that China once again applies property as a growth stabilizer in the second half, and growth eventually will be better than the tapered expectations. The outlook on inflation is gradually converging to consensus, too: in the near term, inflation pressure remains elevated because of rising commodity prices, but its momentum is likely to wane. In the long run, significant income and wealth disparity suppresses demand of the mass, and such secular social problem is unlikely to be resolved in the near term. Inadequate demand means disinflation, or outright deflation (please refer to our report “Decoding Deflation: Principal Contradiction, Social Progress and Market Fragility” on November 14, 2017). The question now is that why bond yields remain elevated, when everyone is staring at the same chart (Exhibit 5)? Exhibit 5: Inflation is losing momentum, but bond yields remain elevated. We note that the US 10-year yield has broken its secular down trend (Exhibit 6). Our special report titled “A Price Revolution - On Global Asset Allocation” on November 14, 2016, and the follow-up report titled “Decoding Deflation: Principal Contradiction, Social Progress and Market Fragility” on November 14, 2017, have discussed the end of the secular bond bull market in details. Our reports concluded that equities will outperform bonds. That said, these long-term outlooks, while important to ponder upon, means less for near-term trading.

Exhibit 6: The US 10-year has broken its 30-year down trend.

We note that the US 10-year yield has broken its secular down trend (Exhibit 6). Our special report titled “A Price Revolution - On Global Asset Allocation” on November 14, 2016, and the follow-up report titled “Decoding Deflation: Principal Contradiction, Social Progress and Market Fragility” on November 14, 2017, have discussed the end of the secular bond bull market in details. Our reports concluded that equities will outperform bonds. That said, these long-term outlooks, while important to ponder upon, means less for near-term trading.

Exhibit 6: The US 10-year has broken its 30-year down trend.

In the short run, factors other than inflation outlook must have kept bond yields elevated. In the US, the Fed is curtailing its balance sheet. As such, a large price taker on the margin in bond trading is dwindling, while the ECB and BoJ both sound hawkish. In China, large price takers on the margin in bond trading, namely commercial banks, are restricted by tighter regulations and liquidity and thus will not to be able to trade as before.

We believe that it is these changes in market trading structure, rather than the outlook on growth and inflation, that are keeping bond yield elevated. If so, elevated bond yields should make bonds look attractive to buyers of large caps who are searching for yield and safety.

The following scenarios are worth considering: 1) if growth should beat, then growth assets such as small caps, EM and commodities should outperform, no matter inflation would ease or not – this is a likely scenario. 2) If growth should disappoint and inflation pressure would ease, then bonds should recover. 3) If growth should disappoint and inflation pressure would not ease, then all bets are off. This would be the worst case scenario.

In the short run, factors other than inflation outlook must have kept bond yields elevated. In the US, the Fed is curtailing its balance sheet. As such, a large price taker on the margin in bond trading is dwindling, while the ECB and BoJ both sound hawkish. In China, large price takers on the margin in bond trading, namely commercial banks, are restricted by tighter regulations and liquidity and thus will not to be able to trade as before.

We believe that it is these changes in market trading structure, rather than the outlook on growth and inflation, that are keeping bond yield elevated. If so, elevated bond yields should make bonds look attractive to buyers of large caps who are searching for yield and safety.

The following scenarios are worth considering: 1) if growth should beat, then growth assets such as small caps, EM and commodities should outperform, no matter inflation would ease or not – this is a likely scenario. 2) If growth should disappoint and inflation pressure would ease, then bonds should recover. 3) If growth should disappoint and inflation pressure would not ease, then all bets are off. This would be the worst case scenario.