Sumedh Deorukhkar, Betty Huang and Xia Le: Trading Blows with the US

2018-04-03 IMI Why is the US at loggerheads with China on trade and investment?

The US has for long voiced that its concern about trade and investment relationship with China. This includes the lack of reciprocity and market access, the absence of a level playing field in China for US investors and more importantly allegations of intellectual property rights (IPR) violation involving forced technology transfer of high-tech US companies in China. Trump believes that US’s $375 bn annual trade deficit with China is ‘out of control’ and caused in large part by unfair Chinese trade practices. In this context, recent US economic literature suggests that between 1999 and 2016, increased competition from Chinese imports cost the US economy 2.65 million jobs, nearly double the 1.4 million jobs lost to automation. In particular, increased trade with China has been found to have led to large job losses in the US manufacturing sector.

Why is the US at loggerheads with China on trade and investment?

The US has for long voiced that its concern about trade and investment relationship with China. This includes the lack of reciprocity and market access, the absence of a level playing field in China for US investors and more importantly allegations of intellectual property rights (IPR) violation involving forced technology transfer of high-tech US companies in China. Trump believes that US’s $375 bn annual trade deficit with China is ‘out of control’ and caused in large part by unfair Chinese trade practices. In this context, recent US economic literature suggests that between 1999 and 2016, increased competition from Chinese imports cost the US economy 2.65 million jobs, nearly double the 1.4 million jobs lost to automation. In particular, increased trade with China has been found to have led to large job losses in the US manufacturing sector.

The scope and substance of US trade war with China remains in a flux

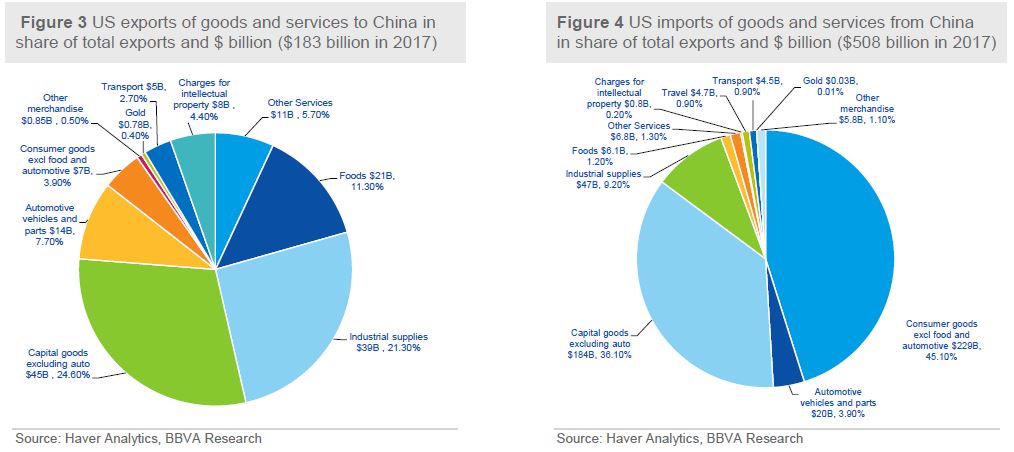

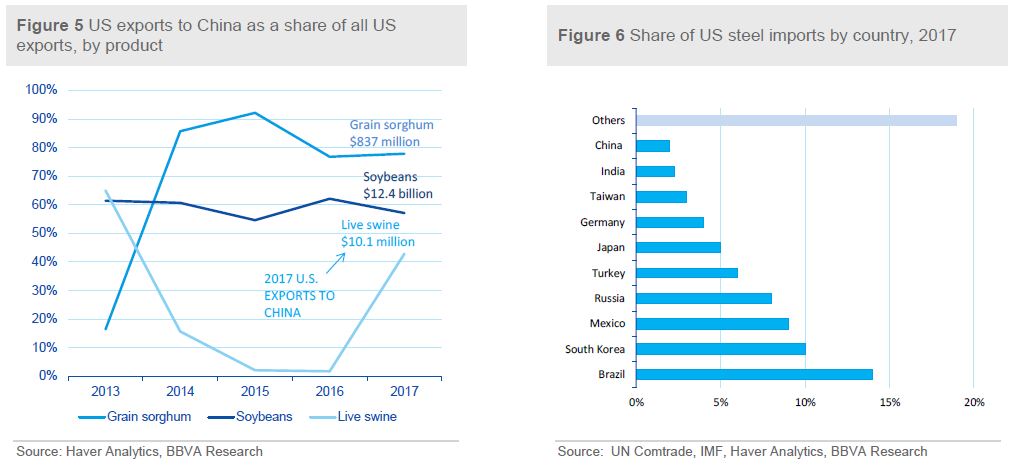

So far, the scope and substance of US tariff package on Chinese imports remains a moving target. The US is putting together a broad-based tariff package that could affect as much as $60 bn or about 10% to 12% of annual goods imports of $506 billion from China in 2017. The US is targeting 1,300 product categories for its 25% tariff package and is expected to publish a formal list in 15 days, while US industry gets 30 days to comment on the products selected for tariffs. Recent comment by US Trade Representative suggests that US tariffs would probably target Chinese high technology industries, aerospace, information and communication technology, and machinery. Separately, US is also mulling tighter restrictions on acquisitions by Chinese companies and technology transfers amid US allegations of Intellectual Property (IP) rights violations by China. In addition, US President Trump has also directed his officials to pursue a World Trade Organization (WTO) complaint against China for discriminatory licensing practices. This suggests that the US intends to tax Chinese technology and intellectual property the most, although it is still unclear whether the tariffs would single out one or two product categories or be broad-based. The former case would have a deeper impact on Chinese economy. Besides the lack of clarity on US action plan, US Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross – a key member of Trump’s core team on trade issues – recently noted that he perceives the strong stand on trade more as a pressure tactic on China to bring concessions without escalating into a broader conflict. As such, before the tariffs become final, there will be a 30-day comment period. This provides a window, albeit short, for the two sides to negotiate and possibly tone down China’s domestically consumed production of oilseeds, the US produces 25% of global oilseed production, followed by Brazil (21%) and Argentina (11%). In this context, China would find it hard to substitute US agri-produce (See Figure –5), at-least in the short term, in turn posing upside risk to domestic inflation. This is more likely if the situation escalates. At under 3% yoy, China’s CPI inflation currently remains well anchored within PBOC’s comfort range, thus allowing policymakers enough room to sustain a respectable growth momentum despite on-going efforts to stabilize debt levels through structural reforms and a prudent monetary policy approach to stem financial fragility risks.

The scope and substance of US trade war with China remains in a flux

So far, the scope and substance of US tariff package on Chinese imports remains a moving target. The US is putting together a broad-based tariff package that could affect as much as $60 bn or about 10% to 12% of annual goods imports of $506 billion from China in 2017. The US is targeting 1,300 product categories for its 25% tariff package and is expected to publish a formal list in 15 days, while US industry gets 30 days to comment on the products selected for tariffs. Recent comment by US Trade Representative suggests that US tariffs would probably target Chinese high technology industries, aerospace, information and communication technology, and machinery. Separately, US is also mulling tighter restrictions on acquisitions by Chinese companies and technology transfers amid US allegations of Intellectual Property (IP) rights violations by China. In addition, US President Trump has also directed his officials to pursue a World Trade Organization (WTO) complaint against China for discriminatory licensing practices. This suggests that the US intends to tax Chinese technology and intellectual property the most, although it is still unclear whether the tariffs would single out one or two product categories or be broad-based. The former case would have a deeper impact on Chinese economy. Besides the lack of clarity on US action plan, US Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross – a key member of Trump’s core team on trade issues – recently noted that he perceives the strong stand on trade more as a pressure tactic on China to bring concessions without escalating into a broader conflict. As such, before the tariffs become final, there will be a 30-day comment period. This provides a window, albeit short, for the two sides to negotiate and possibly tone down China’s domestically consumed production of oilseeds, the US produces 25% of global oilseed production, followed by Brazil (21%) and Argentina (11%). In this context, China would find it hard to substitute US agri-produce (See Figure –5), at-least in the short term, in turn posing upside risk to domestic inflation. This is more likely if the situation escalates. At under 3% yoy, China’s CPI inflation currently remains well anchored within PBOC’s comfort range, thus allowing policymakers enough room to sustain a respectable growth momentum despite on-going efforts to stabilize debt levels through structural reforms and a prudent monetary policy approach to stem financial fragility risks.

Meanwhile, we expect a muted impact on China from the 25% tariffs imposed by US on steel imports and 10% on aluminium imports last week. China isn’t even in the top ten list of countries that export steel to the US, with nearly 53% of China’s steel exports hitting Asian shores (See Figure – 6). Meanwhile, the role of Hong Kong or other foreign intermediary in trade transactions involving the US and China could assume greater importance in light of a protracted trade dispute. Companies on either side could look to bypass trade restrictions and tariffs by choosing to route trade through such foreign intermediaries.

The timing of Trump’s trade aggression towards China seems ironic

While trade and investment disputes between China and the US are nothing new, the timing of Trump’s overt aggression towards China seems odd. The on-going trade clashes come at a time when policy efforts are underway in China to cut-back on excess industrial capacity, including in the metals space. In fact, since 2016, China’s steel exports have nearly halved in level terms while US steel producers are currently seeing their strongest profits in a decade. The latest Beige book on the US economy noted, ‘steel producers reported raising selling prices because of a decline in market share for foreign steel…’. Meanwhile, over the past year, China’s top leadership, including President Xi Jinping as well as former PBOC Governor Zhou, have championed globalisation and reiterated their commitment to promoting free trade and investments and financial liberalization in China.

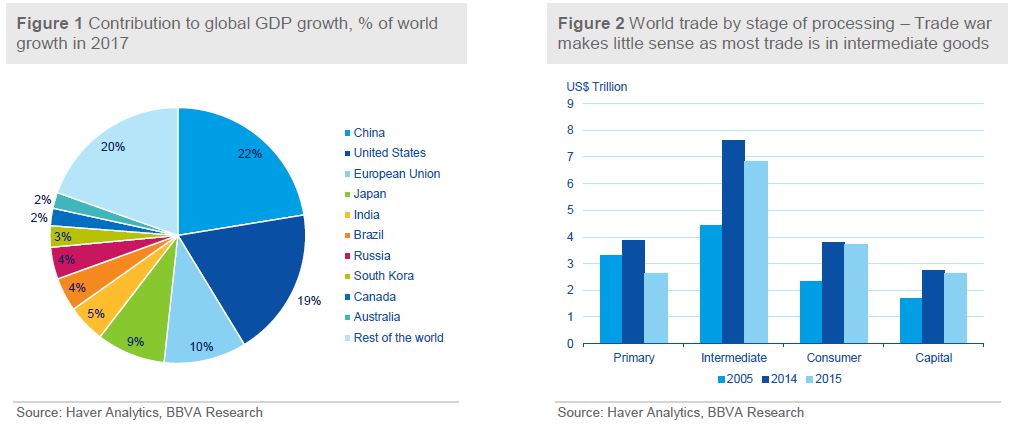

A full-fledged trade-war could put China on the backfoot.

The middle-kingdom stands to take a deeper hit in the event of a full-blown protracted trade war with the US. Imports of Chinese goods and services are about 2.7% of US GDP while exports of US goods and services to China are about 1% of US GDP. Thus, prima-facie, the US has less to lose from a trade-war with China given the massive trade imbalance. The US administration’s intention of a clampdown on higher value-added Chinese imports as well as restrictions on investments by high-tech Chinese companies and technology transfer doesn’t bode well with China’s on-going efforts to achieve a ‘new normal’, leading increasingly to more service and technology-oriented economic growth.

China’s One Belt One Road Initiative (OBOR) as a buffer against US protectionism

The One Belt One Road (OBOR) initiative would help cushion the impact of rising US protectionism by enabling China to better promote its financial institutions and trade integration strategy across other economies (See Figure – 7). The OBOR initiative announced in 2013 has provided an overarching framework for China to achieve its global ambitions; both at the economic as well as strategic level (See our previous two reports on OBOR-Progress and Prospects and OBOR-What’s in it for Latin America?). As China’s President Xi Jinping’s signature move, OBOR, aims to strengthen China’s economic leverage by spearheading infrastructure construction and enhancing connectivity across nearly 70 countries accounting for 33% of global GDP along the overland Silk Road Economic Belt and the Maritime Silk Road across Eurasia. China’s large industrial overcapacity in the wake of on-going economic rebalance, tested expertise in infrastructure, capital account surplus and efforts to secure food and energy resources are well complemented by the need to address infrastructure and funding constraints in most recipient countries of OBOR. OBOR is rapidly expanding in scale, scope and ambition. For economies, such as those in Latin America, which are currently not a part of the initiative but could also suffer from US protectionism, the OBOR platform provides an opportunity to gain deeper access to key Asian markets (See Figure – 8).

Meanwhile, we expect a muted impact on China from the 25% tariffs imposed by US on steel imports and 10% on aluminium imports last week. China isn’t even in the top ten list of countries that export steel to the US, with nearly 53% of China’s steel exports hitting Asian shores (See Figure – 6). Meanwhile, the role of Hong Kong or other foreign intermediary in trade transactions involving the US and China could assume greater importance in light of a protracted trade dispute. Companies on either side could look to bypass trade restrictions and tariffs by choosing to route trade through such foreign intermediaries.

The timing of Trump’s trade aggression towards China seems ironic

While trade and investment disputes between China and the US are nothing new, the timing of Trump’s overt aggression towards China seems odd. The on-going trade clashes come at a time when policy efforts are underway in China to cut-back on excess industrial capacity, including in the metals space. In fact, since 2016, China’s steel exports have nearly halved in level terms while US steel producers are currently seeing their strongest profits in a decade. The latest Beige book on the US economy noted, ‘steel producers reported raising selling prices because of a decline in market share for foreign steel…’. Meanwhile, over the past year, China’s top leadership, including President Xi Jinping as well as former PBOC Governor Zhou, have championed globalisation and reiterated their commitment to promoting free trade and investments and financial liberalization in China.

A full-fledged trade-war could put China on the backfoot.

The middle-kingdom stands to take a deeper hit in the event of a full-blown protracted trade war with the US. Imports of Chinese goods and services are about 2.7% of US GDP while exports of US goods and services to China are about 1% of US GDP. Thus, prima-facie, the US has less to lose from a trade-war with China given the massive trade imbalance. The US administration’s intention of a clampdown on higher value-added Chinese imports as well as restrictions on investments by high-tech Chinese companies and technology transfer doesn’t bode well with China’s on-going efforts to achieve a ‘new normal’, leading increasingly to more service and technology-oriented economic growth.

China’s One Belt One Road Initiative (OBOR) as a buffer against US protectionism

The One Belt One Road (OBOR) initiative would help cushion the impact of rising US protectionism by enabling China to better promote its financial institutions and trade integration strategy across other economies (See Figure – 7). The OBOR initiative announced in 2013 has provided an overarching framework for China to achieve its global ambitions; both at the economic as well as strategic level (See our previous two reports on OBOR-Progress and Prospects and OBOR-What’s in it for Latin America?). As China’s President Xi Jinping’s signature move, OBOR, aims to strengthen China’s economic leverage by spearheading infrastructure construction and enhancing connectivity across nearly 70 countries accounting for 33% of global GDP along the overland Silk Road Economic Belt and the Maritime Silk Road across Eurasia. China’s large industrial overcapacity in the wake of on-going economic rebalance, tested expertise in infrastructure, capital account surplus and efforts to secure food and energy resources are well complemented by the need to address infrastructure and funding constraints in most recipient countries of OBOR. OBOR is rapidly expanding in scale, scope and ambition. For economies, such as those in Latin America, which are currently not a part of the initiative but could also suffer from US protectionism, the OBOR platform provides an opportunity to gain deeper access to key Asian markets (See Figure – 8).