Dong Jinyue and Xia Le: Financing China’s New Stimulus Package: Monetization Is Not the Answer

2020-07-06 IMI

The authorities announced the details of fiscal stimulus package ...

The COVID-19 pandemic has tipped the global economy into a severe recession, which in many aspects led to losses greater than that during the 2008-2009 global financial crisis (GFC). Amid dislocations of the world economy, Chinese authorities announced the monetary and fiscal stimulus package in the recently concluded “two sessions”.

Taking lessons from the contentious “4-trillion” stimulus package unveiled during 2008-2009 GFC, which was widely blamed for causing the debt overhang problem in the ensuing years, the authorities seemingly become more conservative this time in crafting the new stimulating measures. This time around, it is the fiscal easing, rather than the monetary loosening, that plays a leading role while monetary policy coordinates given that the nature of pandemic-driven crisis requires for more targeted measures to offset negative shocks.

In particular, this year’s fiscal stimulus package includes below elements: (i) To expand fiscal deficit rate from 2.8% in the previous year to 3.6%, around RMB 1 trillion increasing; (ii) To issue special government bond with the scale at RMB 1 trillion; (iii) To increase tax cut and fee reduction scale to RMB 2.5 trillion, RMB 0.5 trillion increasing from the previous year ; (iv) To expand local government bond issuance to RMB 3.75 trillion to support infrastructure investment at local government level, increasing by RMB 1.6 trillion from the previous year; and (v) To use part of proceeds from local government bond issuance as seed funds to leverage bank lending, estimated at RMB 1.5 trillion (new increasing in 2020).

Altogether, the current fiscal stimulus package reaches RMB 5 trillion, around 5% of total GDP if we take into account the part (v). It is noted that the size of current fiscal stimulus is way below that of the “4-trillion” stimulus package during 2008-2009 GFC in terms of its share to GDP. In 2008, RMB 4 trillion accounted for 12.5% of China’s then GDP. Moreover, many analysts estimated that the real size of “4-trillion” stimulus package substantially exceeded RMB 4 trillion and could amount to RMB 9 trillion (or 28% of GDP).

The authorities manifest that the unveiled policy initiatives should not be considered as one-off measures. Given great uncertainties surrounding the pandemic, the authorities believe that they need to reserve more fiscal room for further stimulus down in the road.

...while how to finance the fiscal stimulus package ignited drastic debate

The market was concerning how the authorities will finance these fiscal stimulus measures, in particular for the special government bond issuance, and whether these financing channels are sustainable. In June the central government clarified that the special government bond will be issued in the bond market, which, however, failed to quell the debate among Chinese economists and policymakers about whether China’s government should monetarize its fiscal deficit by directly issuing treasury bonds to the central bank. The debate is still relevant and meaningful because more fiscal easing measures are likely to be implemented in the coming years if the Covid-19 pandemic lasts longer.

The debate about fiscal deficit monetarization was sparked by a speech in April 2020 by Mr. Liu Shangxi, who is heading the Chinese Academy of Fiscal Sciences, a think-tank affiliated to Ministry of Finance. In the speech he suggested that the central bank directly buy the newly issued government bonds in the primary market to finance the government’s fiscal deficit. Since such behaviors are forbidden by China’s Central Banking law, Mr. Liu also suggested the authorities amend the law.

However, Mr. Liu’s suggestion of monetarizing fiscal deficit has been widely criticized. Many economists believed that it will undermine fiscal disciplines and sacrifice the independence of the central banking system. Although it seems like a low-cost solution to some acute problems, it will give rise to much more problems than answers in the long run. On the other hand, the supporters of fiscal deficit monetization contended that the boundary between fiscal and monetary policy is blurred in the context of modern central banking system. In the past both Chinese government and some authorities in advanced countries have already made some breakthroughs in shifting the fiscal obligations to the central banks. For example, several policy innovations in advanced economies including QE and yield curve control bear certain features of monetization. Moreover, at the beginning of 2000s China’s authorities used the monetarization as one of the means to bail out its then bad-debt-laden banking system.

The pressure of fiscal deficit monetarization stems from significant shrinking fiscal revenue amid economic recession

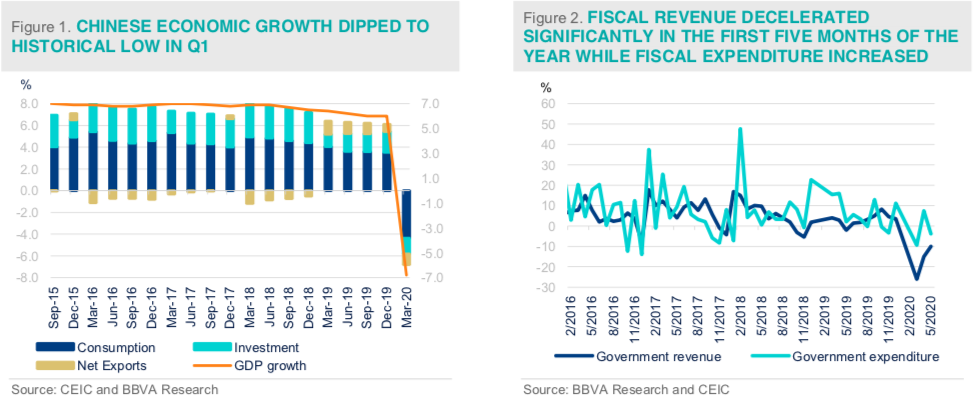

The root reason of such a debate is a significant narrowing of fiscal policy room, namely the dipping fiscal revenue and rising fiscal expenditure amid economic recession caused by COVID-19 pandemic. Actually, China’s economic growth dipped to historical low at -6.8% y/y in Q1 2020, and the whole year growth is expected to be around 2.2% y/y by our estimation, a large plunge from the previous year’s 6% growth. (Figure 1) The growth deceleration together with the ongoing unbalanced recovery will naturally lead to sliding fiscal revenue.

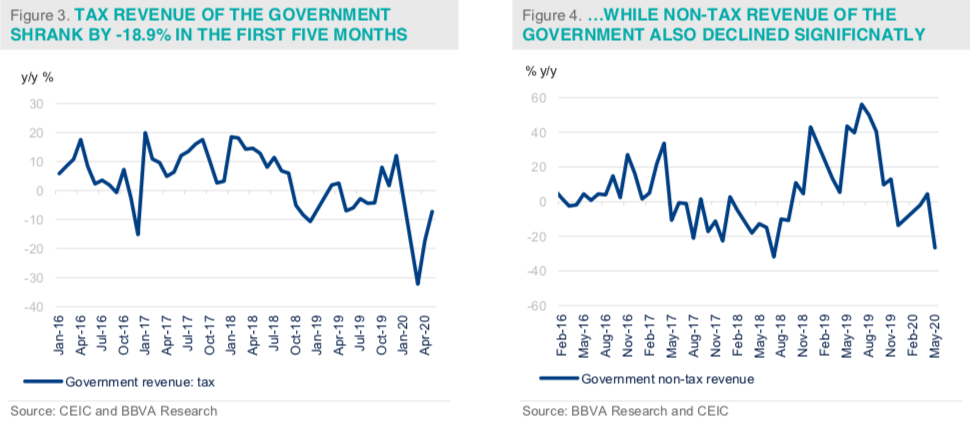

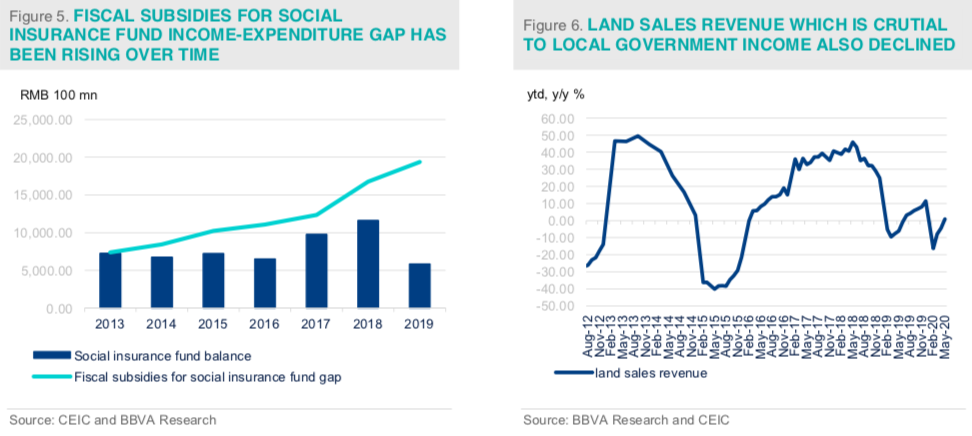

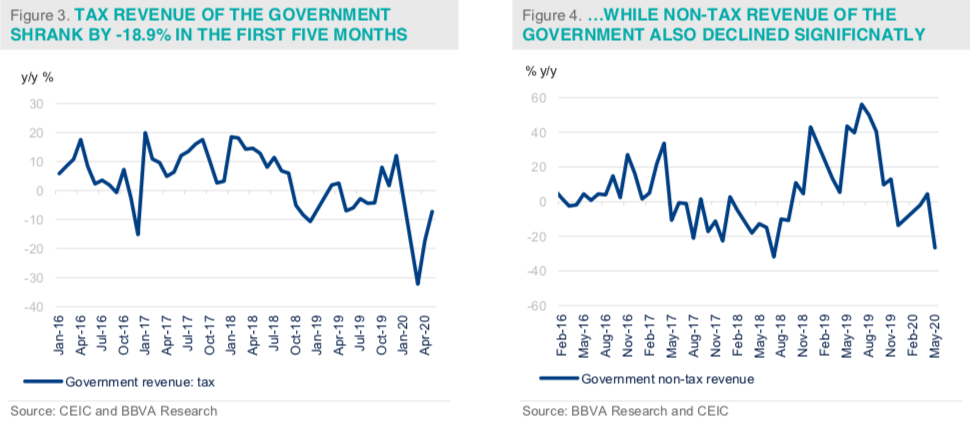

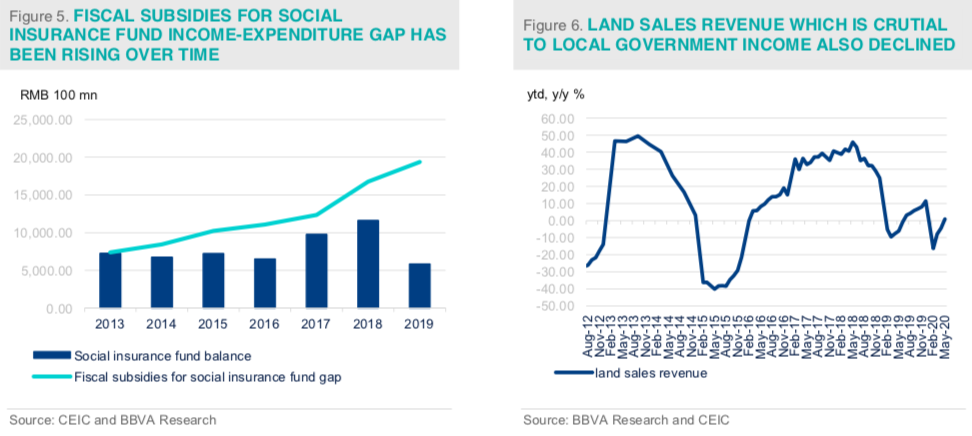

In particular, China’s year on year fiscal revenue growth in January to May dipped significantly to -17% y/y on average (Figure 2), while during the same period of time, fiscal expenditure decreased only by -1.9% y/y. That being said, the gap between the fiscal revenue and expenditure has largely expanded. More importantly, as fiscal easing measures being implemented after the “two sessions”, government expenditure is anticipated to increase faster in the rest of months of this year. While the overall tax income decelerated by -18.9% y/y in the first five months of 2020, the non-tax income also declined by -8% y/y on average during the same period of time. (Figure 3 and 4) In addition, China’s social insurance scheme has also been problematic. The social insurance income- expenditure gap has been expanding with the aging population in the past decade. Thus, fiscal subsidies for the social insurance fund have been continuously rising over time to fill in the gap. (Figure 5)

At the local government level, the land sales revenue which takes a large proportion of local government fund income and is critical to local government fiscal revenue, dropped to -4.5% y/y in the first five months of the year, a sharp decreasing compared with 11.4% growth in the previous year. (Figure 6)

However, fiscal deficit monetarization is not a policy choice yet

Although China’s fiscal revenue at both central and local government level has been shrinking amid economic recession, it does not necessarily mean that the authorities have to adopt the extreme measure to finance the expanding fiscal deficit, such as fiscal deficit monetarization.

The disadvantages of fiscal deficit monetarization, i.e. central bank directly purchasing government bond in the primary market to finance the fiscal deficit, are obvious:

First, fiscal deficit monetarization undermines the well-established fiscal disciplines in China which was introduced and established in the past couple of decades. Under the normal circumstance, if the authorities finance the government bond in the bond market, they have to consider whether they have the ability to pay back the principals and interest rates. If the government substantially increases the government bond supply, it will be punished by the spiking market interest rates. As such, the fiscal authorities have to refrain themselves from spending beyond their means and carefully manage their balance sheets. According to China’s own experience, such fiscal disciplines are of great help to anchoring the inflation expectation of the public and maintain financial stability.

Second, the conduct of fiscal deficit monetization is set to have a strong signal effect under the current circumstance, which could not only lead to large-scaled capital outflows and financial turmoil but also dampen the confidence of global recovery. Global investors always consider China’s central government debt to be well managed and at a comparatively comfortable level despite the country’s massive and opaque debt obligations at the local government level, the chunk of which were borrowed through the notorious local government financing vehicles (LGFVs). If China suddenly announces the monetization of its fiscal deficit, sensitive investors might jump to the conclusion that China’s fiscal system is on the verge of debacle amidst huge shocks of the COVID-19 pandemic. The evaporation of investors’ confidence is likely to exert a catastrophic impact on China’s financial system.

Indeed, there is a lot of room for the authorities to finance the fiscal deficit through conventional channels:

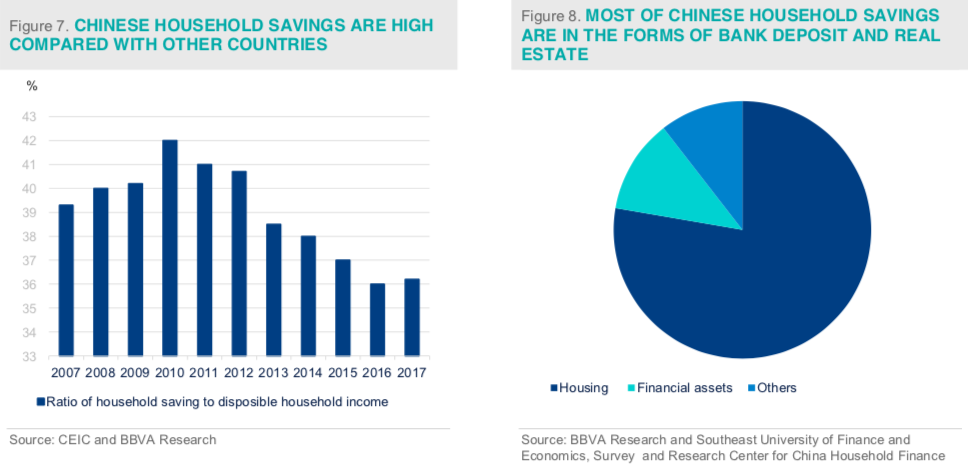

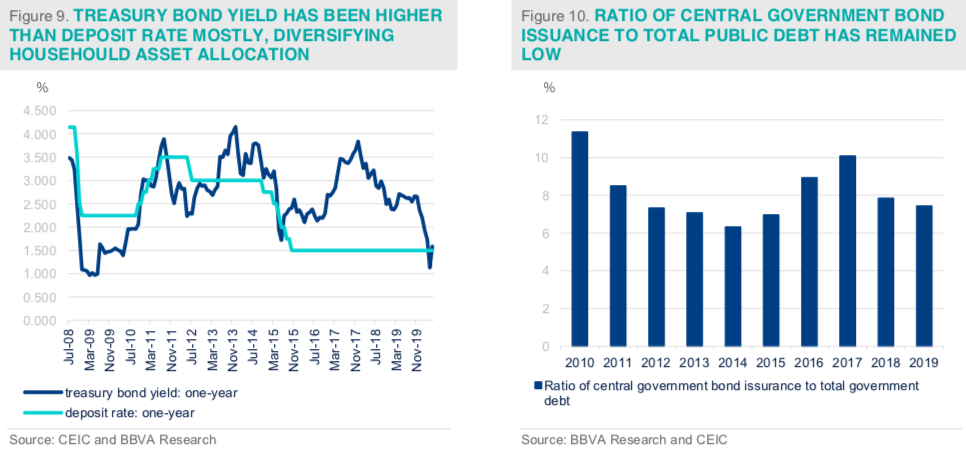

First, Chinese household deposit savings are high compared with those of other countries but the financial depression in China with limited investment choices forced Chinese households to put their savings in the bank deposit and housing market. (Figure 7 and 8) Actually, the demand of government bond in various terms and durations is strong among the individual investors due to its higher interest payment compared with deposit rate and its low risk. (Figure 9) Thus, financing the deficit through government bond issuance in the financial market is equivalent to transfer part of bank deposit to the government bond market, which could diversify households’ investment choices and more importantly complete and smooth the government bond yield curve.

Second, issuing government bond by various terms and durations could attract international investors in Chinese onshore bond market and press ahead capital account opening reform and RMB internationalization. After all, amid global financial market turmoil, Chinese bond yield, with its absolutely higher yield than that of advanced economies and less sovereign risk, attracts global portfolio managers to invest in. Currently, the foreign investors’ share of Chinese bond market only accounts around 1%. That being said, there will be plenty of room to attract capital inflow to domestic bond market.

The authorities need to take some methodical steps to finance their fiscal stimulus package via conventional channels while control the public debt level and maintain financial stability over the longer term. Here are some policy suggestions:

First, the authorities should enhance the degree of transparency in the government fiscal deficit; in particular, by making the contingent LGFV debt more explicit. This will alleviate the problem of the soft budget constraint for local government financing and put the local government debt under public surveillance. In addition, it will help to reduce the systematic financial market risk. Actually, the authorities pushed forward the deleveraging for LGFVs in the past several years and have born some early fruits. However, the ballooning fiscal deficit for the counter-cyclical stimulus measures this year might raise the LGFV borrowing and other forms of local government debt issuance. Thus, controlling the implicit debt at the local government level still constitute a key challenge to the authorities.

Moreover, more fiscal transfer from the central government to local government should be conducted so as to reduce the spending burden of local government. Amid the global economic recession, increasing the ratio of central government fiscal deficit to total public debt could make the fiscal stimulus more targeted and more coordinated at the central government level. Local governments might have less incentive to implement relief measures in support of the COVID-19 affected enterprises and households. Instead, they are more willing to put the money in certain investment projects to pursue high local GDP growth as the officials’ performance is always linked with GDP.

Second, the authorities at last decided to issue special government bonds of RMB 1 trillion with the term of 10-year. The Ministry of Finance should consider increasing the supply of short-term Treasury bonds such as one-year term or even shorter, which will help to cater to the diversified demands of households, enterprises and commercial banks. Moreover, the provision of treasury bonds with various tenors will contribute to completing the yield curve in the secondary bond market.

Third, from the perspective of special local government bonds, how to match these bonds with projects with reasonable return is the key to make the local government debt sustainable in the future. In our previous experience of local government debt overhang, the main reason leading to local government debt accumulation and continuous roll-over is that the local government debt always matched these bonds with low-return and long- term infrastructure projects. That means, without profitable projects, these local government special bonds will unavoidably become the long-term fiscal burden of local governments.

Finally, the authorities need to increase the SOEs’ profit submission to the central to fill in the fiscal gap. Under China’s system, SOEs are entitled to retaining the majority of their earnings even those profits stem from their actual monopolization in their respective sectors. Moreover, Chinese SOEs have easier access to external financing resources and government subsidies. Thus, it is the social responsibility of SOEs to support fiscal revenue amid growth slowdown. Some experts suggested that SOEs should submit their profits to the central government from the current 10%-25% (with different categories) to 30%. We believe that the proportion of profit submission could be increased to a higher level to offset the current shortfall of fiscal resources.

Altogether, regarding the method of financing the new stimulus package, the recent debate of fiscal deficit monetarization is far from a policy choice in view of China’s current macroeconomic circumstances. China still has the room to fill the fiscal gap via the conventional financing channels. In so doing, the authorities will better balance the needs of short-term stimulus and the long-term financial stability as well as fiscal disciplines.