Dong Jinyue and Xia Le: Should we worry about the falling FDI?

2024-01-17 IMIThis article first appeared on BBVA Research on January 10, 2023

Jingyue Dong is Senior Economist for Asia at BBVA Research.Le Xia is Chief Economist for Asia at BBVA Research.

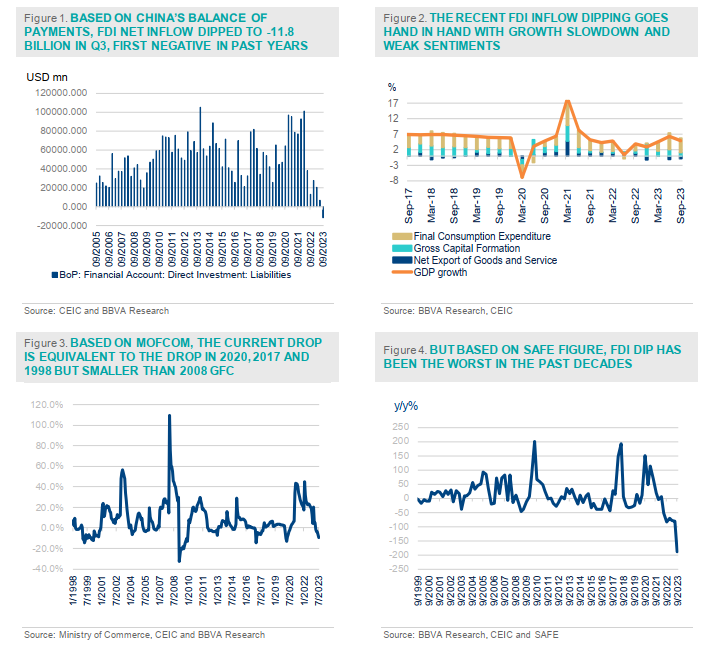

Chinese FDI recently dipped to its historical low, attracting wide market concerns. In particular, based on the Balance of Payment (BoP) data provided by State Administration of Foreign Exchange (SAFE), the net FDI inflow fell to USD -11.8 billion in Q3 2023, registering a negative outturn for the first time over the past decades. (Figure 1)

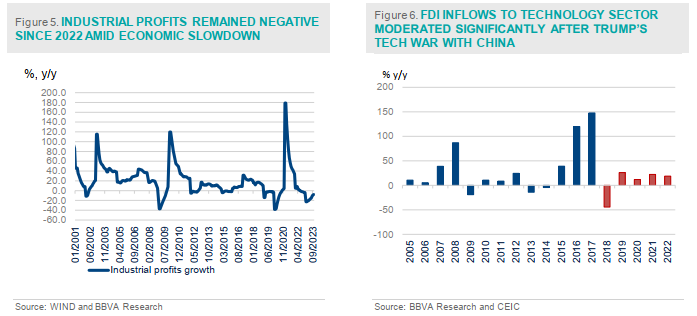

The recent drop happened on the backdrop of China’s escalating geopolitical risks, domestic housing market crash and more importantly, disappointing growth recovery in the aftermath of the nationwide Covid -19 lockdown. (Figure 2)

In this report, we focus on analyzing the following important questions regarding the recent FDI drop in China: (i) How serious is the situation based on different measures provided by SAFE and Ministry of Commerce? (ii) What are the driving forces behind the sharp drop of China’s FDI? Are they cyclical or structural factors? (iii) To what extent does the FDI drop (or the shortage of it) influence China’s economy under current circumstances ? (iv) What measures should the Chinese authorities take to lure them back in the future?

Understanding the recent FDI drop with two different measurements: SAFE and Ministry of Commerce

There are two different indicators that gauge the FDI inflows to China: one is based on Balance Sheet Payment (BoP) data provided by the SAFE (State Administration of Foreign Exchange) while the other is based on the data provided by MOFCOM (Ministry of Commerce). Nowadays, these two indicators differ a lot.

The FDI reported by MOFCOM is declining but doesn’t seem to be that worrisome. Its year-on-year growth is around -10% in the first three quarters of 2023, which is comparable to its performance in 2020 (Covid-19 pandemic), 2017 (China's deleveraging) and 1999 (Asian financial crisis). During the 2008 Global Financial Crisis this indicator dipped by more than -30% y/y. (Figure 3)

However, the FDI indicator reported by the SAFE (Figure 4) shows a dramatic change of -200% y/y over the same period. Such drop is the largest in the past several decades.

The PIIE report by Nicholas R. Lardy (2023) provides a clear and comprehensive exp lanation for the differences between the data reported by the SAFE and the MOFCOM. These differences include:

1. IPOs in offshore markets: SAFE accounts for IPOs in offshore markets, whereas MOFCOM does not include them in their data.

2. Foreign venture capital and private equity investment (VC/PE): SAFE counts VC/PE investments, while MOFCOM does not consider them in their calculations.

3. Reinvested profits and repatriated profits: SAFE includes reinvested profits of foreign firms as inflows of FDI, whereas MOFCOM does not count reinvested profits as FDI inflows. Additionally, repatriated profits of foreign firms operating in China are considered FDI outflows by SAFE but not by MOFCOM.

4. Direct investments in the financial sector: Foreign financial institutions' direct investments in China's financial sector are counted by SAFE but not by MOFCOM.

5. Related foreign firms' bank borrowing: SAFE includes the bank borrowing of related foreign firms (mostly in USD and from foreign banks) to invest in China's branches. For example, Tesla's headquarters borrowing from US banks to invest in China's Tesla branch. This factor is not accounted for by MOFCOM.

Furthermore, it is noteworthy that the decline in Chinese FDI aligns with the global FDI drop. According to UNCTAD data, global FDI also significantly declined by -12% to a level of USD 1.3 trillion in 2022. This decline can be attributed to factors such as rising funding costs (high USD interest rates), geopolitical tensions, and decelerating global FDI returns etc.

Is the ongoing FDI drop structural or cyclical?

We can identify both structural and cyclical factors that contribute to the ongoing significant deceleration of FDI inflows to China. Let us start with those cyclical ones:

First, due to the disappointing growth recovery in 2023, the industrial profits have fallen significantly. As a result, the falling industrial profits of foreign firms lead to their sharp decline in retained reinvested profits, which are counted as FDI by the SAFE. (Figure 5)

Second, the high f unding costs of US dollar, thanks to the Fed’s fast interest rate hikes during 2022-2023, have a significantly negative impact on the PE/VC inflows to China. Meanwhile, multinational firms are reluctant to inject more money into their branches in China due to the elevated financing costs as they usually borrow from the bank in parent company by USD. On the contrary, some foreign companies take advantage of China’s relatively cheaper funds (Figure 7) and borrow working cap ital in China for the use of their overseas operations.

Third, “round-tripping” FDI also matters. Round-tripping FDI refers to the domestic capital that has fled the home country and then flows back in the form of FDI. The round-tripping FDI in China is sizable. People believe that the round-tripping FDI accounts for 20-50% of total FDI based on different methodology of estimation. If the purpose of this round-tripping FDI is to take advantage of cheaper funds from overseas, it is no wonder that this part of FDI collapsed in 2023 due to the rising overseas funding costs amid US interest rate hike. In ad dition, China has strengthened their financial regulations on this kind of potential round-tripping FDI in a bid to circumvent these firms to take advantage of China’s favorable policies to foreign FDI.

On top of the above cyclical factors, a number of structural factors also contribute to the recent large FDI decline.

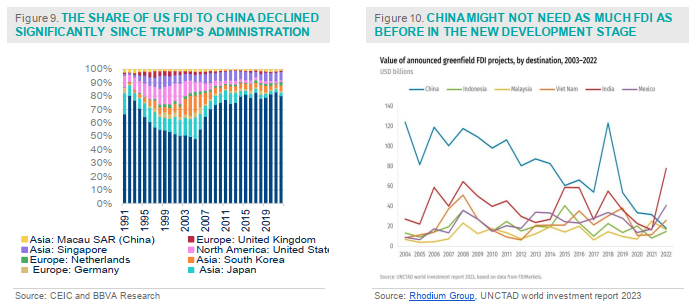

First, the primary structural factor is the global value chain relocation away from China, caused by “decoupling ” or

“de-risking ” policy adopted by the US and its allies. At the same time China’s rising labor costs (Figure 8) also contribute to supply chain relocation. (see our previous China Economic Watch:China | De-Sinicization of Global Value Chain after Covid-19, andChina | Which economies are to benefit from industry relocation?)

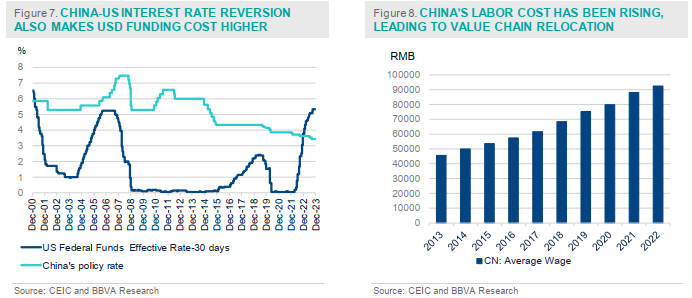

Second, due to the regulatory storms in China in 2021 and the US restrictions on technology investment to China, PE/VC investment in China’s technology sector has decelerated very fast recently. The sharp drop of PE/VC investment in Chinese technology sector contributes significantly to SAFE source of FDI drop (as MOFCOM does not count this part).

For instance, in August 2023, the US President Biden signed the screening mechanism of foreign direct investment, restricting the US entities to invest in China’s semiconductor, AI and qu antum information technology etc. The similar investment restrictions were implemented in Japan too. Beyond that, the Japanese government during the Covid-19 pandemic time provided subsidies to encourage Japanese firms to relocate their global value chains back to Japan.

Some more recent surveys conducted by Japanese Chamber of Commerce and the US Chamber of Commerce also illustrate that the foreign companies hesitate to invest in China amid rising US-China tensions. For instance, in a September 2023 survey of member companies by the Japanese Chamber of Commerce and Industry in China, nearly half of respondents said they would not invest in China at all in 2023 or invest less than in 2022. Escalating tensions with the U.S. are one reason for the decline in foreig n investment. In a survey taken last fall by the American Chamber of Commerce in China, 66% of member respondents cited rising bilateral tensions as a business challenge in China.

Another direct evidence is that the share of the US FDI to China has moderated significantly after the start of Trump Administration. (Figure 9)

Third, another structural factor is that China might not need as much FDI as before in China’s new economic development stage.

Figure 10 illustrates this point. By analyzing the FDI inflows for main emerging economies, we find that countries such as India, Vietnam, Mexico, Indonesia etc. that are trying to copy “China model” in 2000s all recorded rising FDI inflows. By contrast, China’s FDI inflows have been declining over time in the past years. (Figure 10) Together with China’s development model transformation from export-oriented and processing trade-oriented economy to consumption and high-end manufacturing-oriented economy, China might not need as much as FDI inflows as before back to 1990s and 2000s. (We will further discuss this issue in the next session)

The above structural factors are likely to persist in the foreseeable future. That being said, we believe China’s FDI inflows won’t bounce back to their level of 1990s and 2000s even if those cyclical factors turn favorable again.

Is it a big issue given that China has become an international creditor?

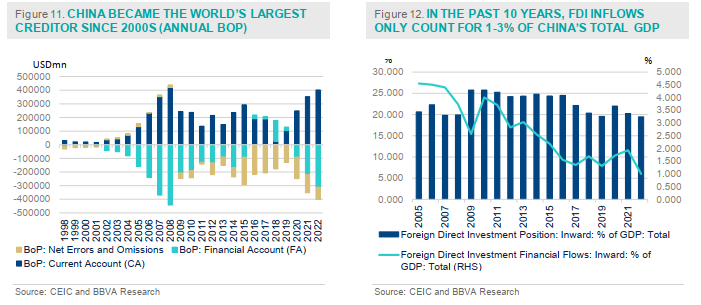

Countries’ demand for FDI inflows vary with their different economic development stages. China has become a net creditor in the world since 2000s. It will naturally beg the question whether China needs FDI as much as before. (Figure 10)

According to the Development Economy theory, when a country migrates from a low-income economy to a middle- to-high income (or high income) economy, usually it lacks capital but has natural endowments of labor and resources. During the transformation period, they need more FDI inflows so as to combine with the domestic cheap labor and resources to pursue economic growth. However, when a country becomes a middle-to-high- or high- income economy, its labor cost will go up significantly while they should have already accumulated abundant

capital for investment. At this stage, it does not need as much FDI inflows as before. (Figure 11)

China’s growth trajectory is consistent with this economic development theory. In the past ten years from 2013 to 2022, the ratio of FDI inflows to China’s total GDP has been declining from 3% to 1%; and the net FDI position (the stock) to GDP ratio also declined from 24% to 19%. (Figure 12) Given China’s stunning economic performance in

2013-2022, during which FDI inflows has experienced gradual slowdown, it indicates that the role of FDI inflows might not be as important as in the period from 1980s to 2000s.

Is foreign FDI inflow still important for Chinese economy?

However, even at China’s new economic development stage, the indirect effect of FDI decline is much more important and nuanced than its direct effect as stated above.

In particular, FDI inflows usually bring about technology advancement, “learning -by-doing” effect, advanced management methods, international standards and more crucially, the competition which lead to the increase of total factor productivity domestically.

The OECD paper (2000) comprehensively summarized the indirect effects in China, including: (1) FDI – An increasingly important source of capital; (2) FDI has created jobs; (3) FDI has upgraded skills; (4) FDI has paid higher wages; (5) FDI has raised factor productivity and increased technology transfer; (6) FDI has modified China’s industrial structure; (7) FDI has increased domestic competition; (8) FDI has increased industrial performance.1

For instance, Apple Inc.’s investment and large presence in China brings about fierce competition among domestic smart phone markets and thus foster a series of domestic smart phone brands, such as Huawei, Xiaomi, and Vivo etc. which recently become the rising stars in the global smart phone market. In addition, Tesla mega factory in Shanghai also brings about high technology and competition in domestic EV market which fosters domestic EV brand such as BYD etc., that ultimately leads to China’s EV market going to the frontier of the world.

Although China has experienced the global value chain relocation away from China in the labor-intensive low-end sectors, such as textile, footwear, clothing, furniture etc., China in the recent years still attracts FDI inflows in high- end manufacturing sectors: chemical sector, auto making, EV, green energy, semiconductor, telecommunication and pharmacy etc. This is definitely in line with the national strategy of developing “high-end manufacturing ” and fostering China to be the world ’s “high-end manufacturing ” center in the world, following German model or Japan model. That means, attracting FDI in high-end manufacturing sector and taking use of its “learning-by-doing ” and technology spillover effect is crucial in China’s new development stage.

What should Chinese government do to attract FDI inflows to high-end manufacturing sectors?

Attracting foreign direct investment (FDI) and guiding it into high-end manufacturing sectors is a crucial policy objective for the Chinese government in the future. China’s authorities should take important lessons and open their arms to foreign investors.

First of all, Chinese government should persist the long-lasting “reform and opening up policy ” and improve foreign investor’s sentiments to invest in China by promulgating more preferential policies on foreign FDI. These policies not only include reducing negative list, providing more equal environment for foreign firms with domestic firms, expanding market entry conditions, but also include providing “national treatment” principle for foreign firms and protecting IPR (intellectual property rights), etc.

Second, Chinese government needs to continue to support Chinese economic growth and to avoid systemic financial risks, as the stable and prosperous domestic environment is the prerequisite of foreign FDI inflows. For the historical experience, FDI inflows have a synchronized relationship with domestic G DP growth, as more prosperous growth outlook leads to larger corporate profits , thus higher FDI investment returns and better foreign investor sentiments. In the future, Chinese government not only needs to secure the economic soft -landing, but also to contain domestic financial risks in real estate sector, local government debt as well as small financial institutions’ default risk. A more robust domestic financial condition will also help to support foreign investors ’ sentiments.

Third, Chinese government needs to stabilize China-US relationship as well as to deepen investment and trade relationship with One Belt One Road (OBOR) and RCEP countries. Although the China-US’s long-term trade war, technology war and finance war will persist in the future, Chinese g overnment should never abandon their effects to stabilize its relation with the US. The most recent case is the Biden-Xi meeting during APAC meeting in San Francisco at end-2023 which, to a certain extent, could help mitigate the conflicts. Regarding the trade and investment relationship with OBOR and RCEP countries, China should expand its own allies to confront the exclusion from the western allies regarding investment and trade linkages.

Last but not least, China’s authorities should become humbler if they want to lur e foreign investors back. The authorities should carefully listen to foreign investors and help them to solve pain points in their investment. In response to investors’ dampened confidence and increasing concerns, the authorities should clearly deliver the message to the world that they are still prioritize economic growth and social development.