Dong Jingyue and Xia Le:China Economic Outlook. Fourth Quarter 2019

2019-10-23 IMI- i) a 10 bps cut to -0.50% in the deposit interest rates; ii) the adoption of a two-tiered system for bank deposits in the central bank; iii) a new quantitative easing program, totaling EUR 20 billion per month and which will continue "until before interest rates begin to rise"; iv) more attractive conditions for banks at the institution's new targeted longer-term refinancing operations (TLTRO III). Moreover, the ECB's forward guidance has been adjusted to reinforce the accommodative tone. In China, in addition to actions taken in the fiscal area and the exchange rate depreciation, a 50 bpscut in reserve requirements for banks has recently been announced. In addition, between July and September, official interest rates have been reduced from 4.35% to 4.20%.

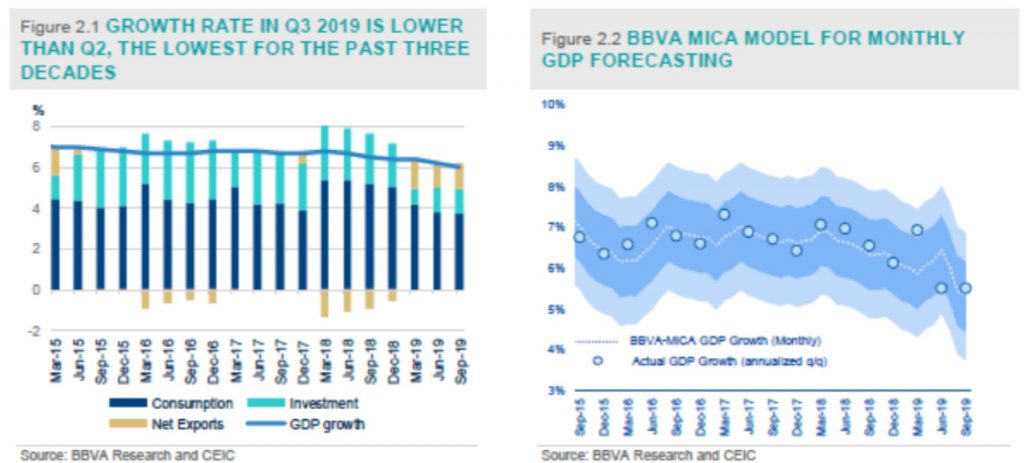

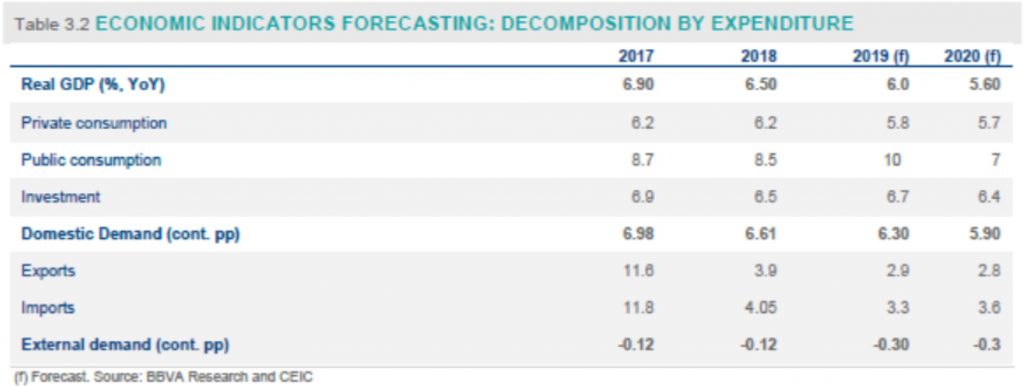

By category, the contribution of consumption to GDP growth reached 3.75%, slightly lower than the previous quarter’s reading at 3.79%, indicating a lower consumer’s willingness amid economic uncertainties. On the other hand, due to the authorities’ stimulus measures on investment, the contribution of investment to GDP growth increased from 1.21% in Q2 to 1.23%. However, the contribution of net exports to GDP decreased to 1.22% from 1.3% in Q2, as the trade war effect on exports intensified.

The Q3 GDP slowdown was mainly led by July and August, while some of the September outturns are actually better-than-expected. However, the good September outturns might highly depends on the seasonal effect.

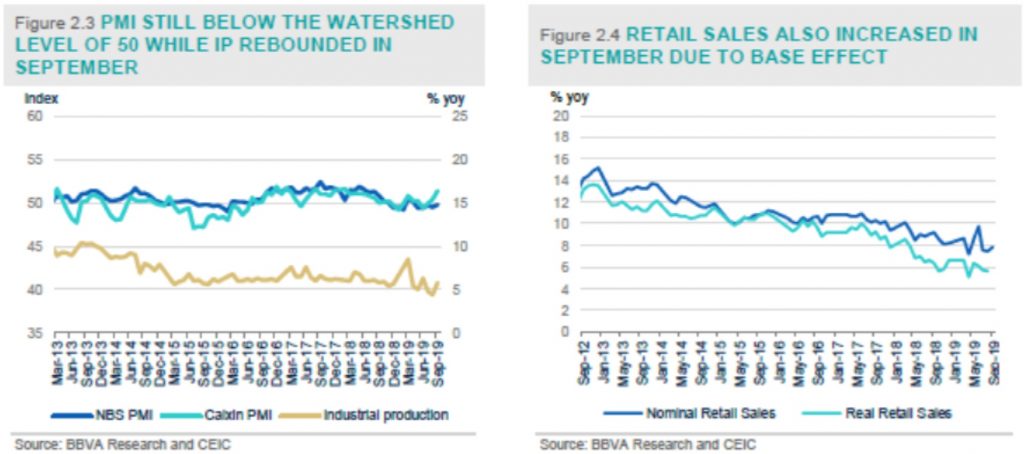

The performance of the supply side worsened after the US-China trade war reignited in Q2, together with the domestic structural obstacles, dampening the producers’ sentiment. Regarding the PMI surveys, the NBS PMI, which tilts towards large and medium size SOEs, although marginally picked up from 49.5 to 49.8 in September, still below the watershed level of 50. On contrary, Caixin PMI whose sample tilts toward SMEs picked up significantly from 50.4 to 51.4 in September. Due to the seasonal effect, industrial production surprisingly rebounded to 5.8% y/y in September from 4.4% y/y in the previous month (consensus: 4.9% y/y). However, the 5.8% y/y growth of industrial production still remains in the contraction region. (Figure 2.3)

On demand side, the growth of retail sales in September picked up to 7.8% y/y from 7.5% in the previous month. (Figure 2.4) However, the auto sales growth significantly declined in September at -2.2% y/y which is much lower than its high growth rate in June at 17.2% y/y, reflecting that people become more conservative in consuming durable goods amid growth slowdown. The only silver lining is the online shopping growth, which maintained the fast speed of growth at 20.5% y/y in January to September.

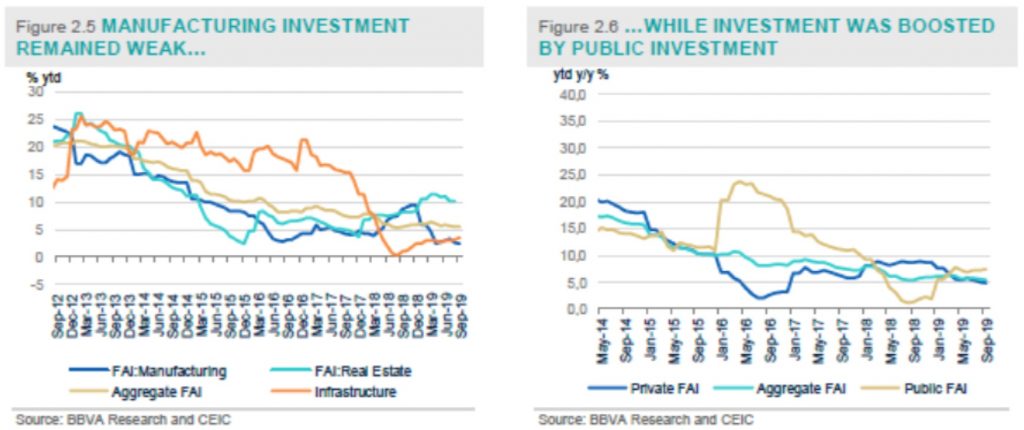

Performance of investment is quite mixing by category in the third quarter. Manufacturing investment extended its weakness in Q3, indicating that amid the unsettled trade war with the US, the recovery in confidence is not entrenched to stimulate producers to expand their capacity. At the same time, the authorities’ easing efforts have boosted the investment in the property sector and infrastructure sector. The growth rate of infrastructure investment rebounded strongly in the third quarter, thanks to the fiscal easing measures in infrastructure construction. Although the stabilization of investment is welcomed, the composition of current recovery is not very healthy as investment in infrastructure projects always leads to the rise of debt level due to their weak profitability. (Figure 2.5 and 2.6)

By category, the contribution of consumption to GDP growth reached 3.75%, slightly lower than the previous quarter’s reading at 3.79%, indicating a lower consumer’s willingness amid economic uncertainties. On the other hand, due to the authorities’ stimulus measures on investment, the contribution of investment to GDP growth increased from 1.21% in Q2 to 1.23%. However, the contribution of net exports to GDP decreased to 1.22% from 1.3% in Q2, as the trade war effect on exports intensified.

The Q3 GDP slowdown was mainly led by July and August, while some of the September outturns are actually better-than-expected. However, the good September outturns might highly depends on the seasonal effect.

The performance of the supply side worsened after the US-China trade war reignited in Q2, together with the domestic structural obstacles, dampening the producers’ sentiment. Regarding the PMI surveys, the NBS PMI, which tilts towards large and medium size SOEs, although marginally picked up from 49.5 to 49.8 in September, still below the watershed level of 50. On contrary, Caixin PMI whose sample tilts toward SMEs picked up significantly from 50.4 to 51.4 in September. Due to the seasonal effect, industrial production surprisingly rebounded to 5.8% y/y in September from 4.4% y/y in the previous month (consensus: 4.9% y/y). However, the 5.8% y/y growth of industrial production still remains in the contraction region. (Figure 2.3)

On demand side, the growth of retail sales in September picked up to 7.8% y/y from 7.5% in the previous month. (Figure 2.4) However, the auto sales growth significantly declined in September at -2.2% y/y which is much lower than its high growth rate in June at 17.2% y/y, reflecting that people become more conservative in consuming durable goods amid growth slowdown. The only silver lining is the online shopping growth, which maintained the fast speed of growth at 20.5% y/y in January to September.

Performance of investment is quite mixing by category in the third quarter. Manufacturing investment extended its weakness in Q3, indicating that amid the unsettled trade war with the US, the recovery in confidence is not entrenched to stimulate producers to expand their capacity. At the same time, the authorities’ easing efforts have boosted the investment in the property sector and infrastructure sector. The growth rate of infrastructure investment rebounded strongly in the third quarter, thanks to the fiscal easing measures in infrastructure construction. Although the stabilization of investment is welcomed, the composition of current recovery is not very healthy as investment in infrastructure projects always leads to the rise of debt level due to their weak profitability. (Figure 2.5 and 2.6)

Inflation picked up on rallying pork prices

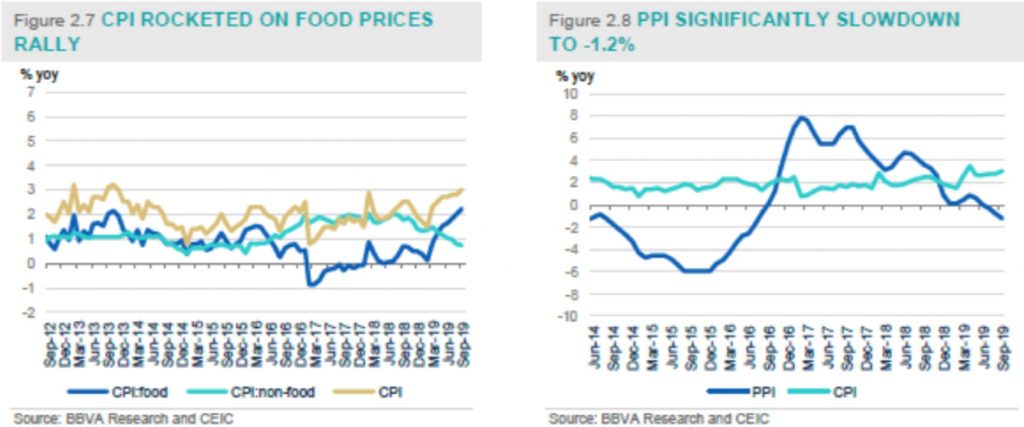

Headline CPI inflation has been rallying in the past months due to the rocketing pork price caused by the breakup of African Swine Fever in China. In particular, September pork price increased by 69.3% y/y, and it increased by 21.3% y/y for January to September as a whole. In September, CPI growth increased to 3% y/y from 2.8% y/y in the previous month. Aggregately, CPI growth increased to 2.9% y/y in Q3, compared with the average of 2.2% in 1H.

The rampant African Swine Fever led to the substantial supply reduction in pork and thereby contributed to the rise of food prices. At the same time, non-food prices were still tame with a growth rate of 1% y/y, lower than the January to September average of 1.5%. (Figure 2.7) PPI growth significantly slowed to -1.2% from -0.8% in the previous month, in line with the authorities’ hold-on of the previous deleveraging campaign amid growth slowdown. (Figure 2.8)

Altogether, we believe that the general price level is still manageable: First, in the recently announced Phase One deal with the US, China will buy a large amount of pork from the US, which will have downward pressure on pork price domestically. Second, based on the Phase One deal, China and the US will sign a currency pact, which refraining China from currency devaluations. That means, the appreciation pressure of RMB will maintain domestic CPI at a contained level. Third, the announced cuts in VAT and other tax at the first half this year will have downward pressure on general price level as well. Finally, the deceleration of Production Price Index (PPI), currently at the -1.2% y/y growth rate, could offset the food price run-up as the industrial related prices declined. There could be pass-through effects from the weak PPI to non-food prices as Chinese authorities have downplayed the previous de-leveraging campaign amid growth slowdown.

Inflation picked up on rallying pork prices

Headline CPI inflation has been rallying in the past months due to the rocketing pork price caused by the breakup of African Swine Fever in China. In particular, September pork price increased by 69.3% y/y, and it increased by 21.3% y/y for January to September as a whole. In September, CPI growth increased to 3% y/y from 2.8% y/y in the previous month. Aggregately, CPI growth increased to 2.9% y/y in Q3, compared with the average of 2.2% in 1H.

The rampant African Swine Fever led to the substantial supply reduction in pork and thereby contributed to the rise of food prices. At the same time, non-food prices were still tame with a growth rate of 1% y/y, lower than the January to September average of 1.5%. (Figure 2.7) PPI growth significantly slowed to -1.2% from -0.8% in the previous month, in line with the authorities’ hold-on of the previous deleveraging campaign amid growth slowdown. (Figure 2.8)

Altogether, we believe that the general price level is still manageable: First, in the recently announced Phase One deal with the US, China will buy a large amount of pork from the US, which will have downward pressure on pork price domestically. Second, based on the Phase One deal, China and the US will sign a currency pact, which refraining China from currency devaluations. That means, the appreciation pressure of RMB will maintain domestic CPI at a contained level. Third, the announced cuts in VAT and other tax at the first half this year will have downward pressure on general price level as well. Finally, the deceleration of Production Price Index (PPI), currently at the -1.2% y/y growth rate, could offset the food price run-up as the industrial related prices declined. There could be pass-through effects from the weak PPI to non-food prices as Chinese authorities have downplayed the previous de-leveraging campaign amid growth slowdown.

Monetary easing and the LPR reform helped to boost credit growth

In response to the growth slowdown amid the unsettled trade war with the US, the authorities unveiled a number of monetary and fiscal measures to stimulate domestic demand starting from 2H 2018. More importantly, in order to solve the monetary policy transmission problem, the PBoC also dropped the previous benchmark lending rate as the monetary policy rate and set the Loan Prime Rate (LPR) as the new target rate, which is expected to smooth the transmission mechanism. Other monetary easing measures include two times of RRR cuts in 2019, lowering the market lending rates (such as DR007, LPR, etc.) and facilitating Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) financing.

On the other hand, fiscal easing measures include a series of tax cuts with total amount of RMB 2 trillion in 2019, expanding local government bond issuance, allowing local governments to use local government special bonds as equity capital to borrow from markets and planning to issue Special Construction Bond (SCB) to support infrastructure investment etc.

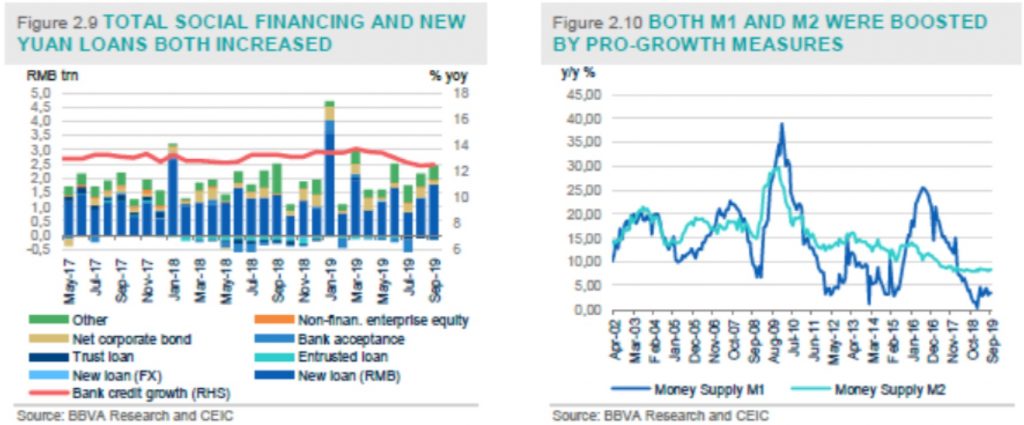

These implemented pro-growth initiatives tended to lend strong support of credit growth. In this respect, both bank loans and the total social financing (TSF) which is a broader gauge of total credit in the economy including both bank loans and other forms of shadow banking activities registered a visible growth through the third quarter. In particular, new yuan loans increased from RMB 1,210 billion to RMB 1,690 billion (Consensus: RMB 1,360 billion) and total social financing also accelerated from RMB 2,017.5 billion to RMB 2,270 billion (Consensus: 1,900 billion) in September. (Figure 2.9) Altogether, M2 growth picked up to 8.5% y/y from the previous month’s reading of 8.2% y/y. (Figure 2.10)

Monetary easing and the LPR reform helped to boost credit growth

In response to the growth slowdown amid the unsettled trade war with the US, the authorities unveiled a number of monetary and fiscal measures to stimulate domestic demand starting from 2H 2018. More importantly, in order to solve the monetary policy transmission problem, the PBoC also dropped the previous benchmark lending rate as the monetary policy rate and set the Loan Prime Rate (LPR) as the new target rate, which is expected to smooth the transmission mechanism. Other monetary easing measures include two times of RRR cuts in 2019, lowering the market lending rates (such as DR007, LPR, etc.) and facilitating Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) financing.

On the other hand, fiscal easing measures include a series of tax cuts with total amount of RMB 2 trillion in 2019, expanding local government bond issuance, allowing local governments to use local government special bonds as equity capital to borrow from markets and planning to issue Special Construction Bond (SCB) to support infrastructure investment etc.

These implemented pro-growth initiatives tended to lend strong support of credit growth. In this respect, both bank loans and the total social financing (TSF) which is a broader gauge of total credit in the economy including both bank loans and other forms of shadow banking activities registered a visible growth through the third quarter. In particular, new yuan loans increased from RMB 1,210 billion to RMB 1,690 billion (Consensus: RMB 1,360 billion) and total social financing also accelerated from RMB 2,017.5 billion to RMB 2,270 billion (Consensus: 1,900 billion) in September. (Figure 2.9) Altogether, M2 growth picked up to 8.5% y/y from the previous month’s reading of 8.2% y/y. (Figure 2.10)

Housing prices picked up in Q3 but with slower growth rate

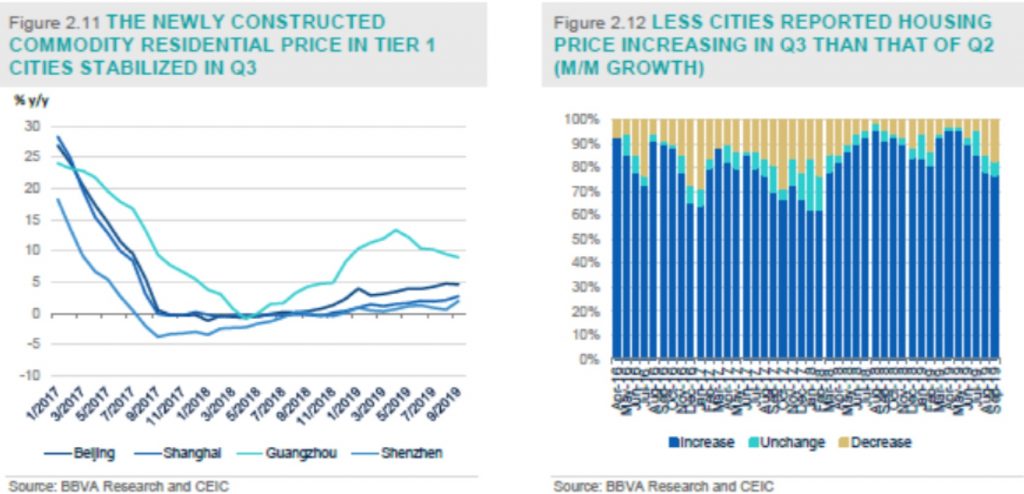

The housing market also benefited from the authorities’ easing measures which have lowered the financing cost. On the other hand, the authorities reiterated their stance of containing housing prices throughout the country in order to avoid another round of housing bubbles amid easing measures. Generally speaking, housing prices still picked up in Q3, but with a slower growth rate compared with those of Q2. In addition, the prices varied significantly from tier-1 to tier-3 cities.

In particular, for tier-1 cities, the average of tier-1 cities’ price increased by 4.6% y/y for newly constructed commodity residential housing in September, compared with 4.2% y/y in the previous month; while for tier-2 and tier-3 cities, the price growth rate declined to 9.3% y/y and 8.4% respectively, compared with 9.9% and 9% y/y in the previous month, but still much higher than that of the tier-1 cities.

Among the 70-city sample provided by the NBS, less cities reported month-on-month increase on their housing prices than that of in Q2. Specifically, there are 54 cities reported housing price increasing in September, compared with 63 cities in June, indicating a gradual housing price slowdown nationwide.

For the positive side, the expansionary housing market could help to boost domestic demand in both related household consumption such as home appliance and investment in the property sector amid the growth slowdown. However, it adds to policymakers’ concern of asset bubble and could further hinder the authorities from doing more policy easing. Thus, how to balance the above two is a challenging job for the authorities. (Figure 2.11 and 2.12)

Housing prices picked up in Q3 but with slower growth rate

The housing market also benefited from the authorities’ easing measures which have lowered the financing cost. On the other hand, the authorities reiterated their stance of containing housing prices throughout the country in order to avoid another round of housing bubbles amid easing measures. Generally speaking, housing prices still picked up in Q3, but with a slower growth rate compared with those of Q2. In addition, the prices varied significantly from tier-1 to tier-3 cities.

In particular, for tier-1 cities, the average of tier-1 cities’ price increased by 4.6% y/y for newly constructed commodity residential housing in September, compared with 4.2% y/y in the previous month; while for tier-2 and tier-3 cities, the price growth rate declined to 9.3% y/y and 8.4% respectively, compared with 9.9% and 9% y/y in the previous month, but still much higher than that of the tier-1 cities.

Among the 70-city sample provided by the NBS, less cities reported month-on-month increase on their housing prices than that of in Q2. Specifically, there are 54 cities reported housing price increasing in September, compared with 63 cities in June, indicating a gradual housing price slowdown nationwide.

For the positive side, the expansionary housing market could help to boost domestic demand in both related household consumption such as home appliance and investment in the property sector amid the growth slowdown. However, it adds to policymakers’ concern of asset bubble and could further hinder the authorities from doing more policy easing. Thus, how to balance the above two is a challenging job for the authorities. (Figure 2.11 and 2.12)

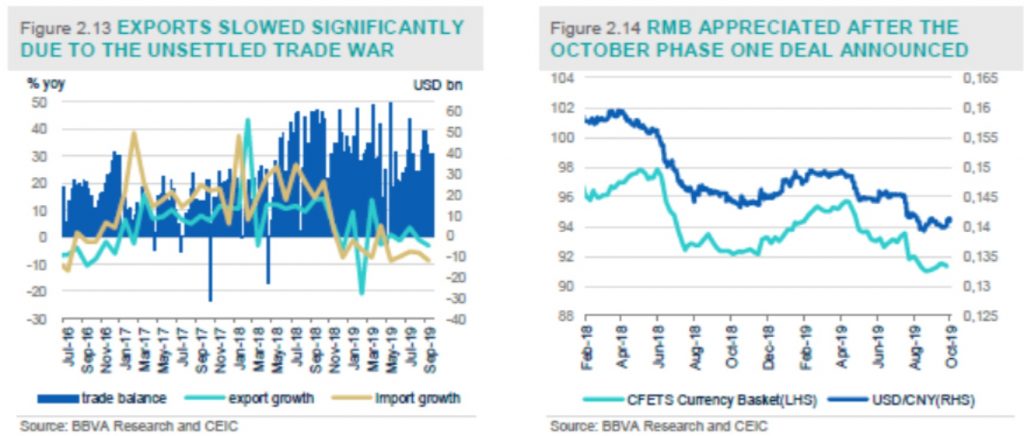

Dipping exports and volatile RMB exchange rate

Both exports and imports slowed down significantly in September due to the weakening of external and domestic demand. In particular, exports further declined to -3.2% y/y in September from -1% y/y in the previous month (Bloomberg consensus: -3% y/y), while imports growth also expanded its decreasing to -8.5% y/y from -5.6% previously (Bloomberg consensus: -6% y/y). Altogether, the trade balance in September expanded marginally from USD 34.78 billion to USD 39.65 billion (Bloomberg consensus: USD 34.75 billion). The combination of downward trend of both imports and exports is expected to last for a long period of time due to the unsettled trade war especially the tariffs that were already imposed. (Figure 2.13)

Dipping exports and volatile RMB exchange rate

Both exports and imports slowed down significantly in September due to the weakening of external and domestic demand. In particular, exports further declined to -3.2% y/y in September from -1% y/y in the previous month (Bloomberg consensus: -3% y/y), while imports growth also expanded its decreasing to -8.5% y/y from -5.6% previously (Bloomberg consensus: -6% y/y). Altogether, the trade balance in September expanded marginally from USD 34.78 billion to USD 39.65 billion (Bloomberg consensus: USD 34.75 billion). The combination of downward trend of both imports and exports is expected to last for a long period of time due to the unsettled trade war especially the tariffs that were already imposed. (Figure 2.13)

The RMB to USD exchange rate has experienced a roller-coaster up-and-down in Q3. On August 5th, the PBoC allowed the RMB to USD exchange rate exceeding the important psychological level of 7 for the first time since 2008, amid the renewed escalation of the China-US trade war due to Trump’s latest tariff hike. The psychological level of 7.0 has been broken in both onshore and offshore market. The market widely believes that it is the retaliated method by the PBoC to respond Trump’s tariff imposing. The currency depreciation beyond 7 implied that Chinese policymakers will take a tougher stance to react to Trump's tariff threat. Actually, in the past, China's authorities painstakingly kept the currency stable so as to alleviate Trump's critique of currency manipulation.

After the PBoC allowed the RMB to USD exchange rate plunging beyond 7 in early August, the RMB has been in a fast depreciation trend from August to early October until most recently the trade war achieved the Phase One deal progress. The RMB exchange rate experienced a rally by 1.1% accumulatively right after the China-US Phase One deal was announced in the second week of October as the talk has raised prospects of the Phase One deal that could include a currency pact. In the rest of this year, we believe that the RMB to USD exchange heavily will depend on the China-US trade talk progress. (Figure 2.14)

According to the US side, the currency pact with China may be similar to the proposed United States-Mexico- Canada Agreement (USMCA), including refraining from currency devaluations to seek trade advantage and also increases transparency of information sharing about government foreign exchange operations such as currency market interventions. More importantly, the currency pact term, which is anticipated widely in the market that Trump, might request China to appreciate RMB to the pre-trade war level (6.8-6.9 around).

Capital outflows accelerated but still manageable

Thanks to the authorities’ tenacious efforts to push for the opening of China’s domestic capital market, China’s equity and bond market was included in MSCI Emerging market Index and Bloomberg-Barclay Index in the first quarter of this year. It means that many passive investors around the world have to increase their exposure to China’s capital market so as to benchmark their portfolio to these Index. Such a positive shift has resulted in a considerable size of capital inflows over the past few months.

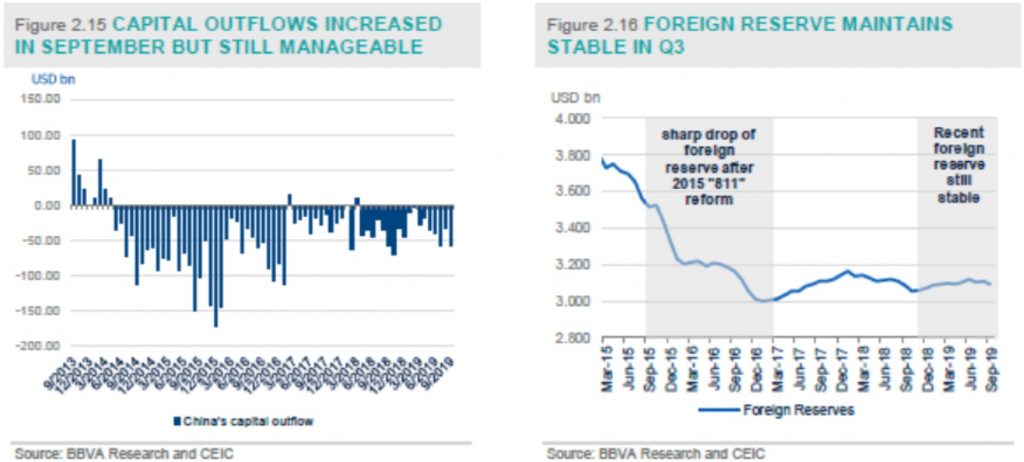

However, given that the trade war has still unsettled, before the Phase One deal in October, the RMB depreciation expectation still dominated capital outflows. Based on our capital outflow estimation model, the September capital outflow reached RMB 57.18 billion, larger than the August’s outflow of RMB 33.29 billion. The accelerating capital outflow is mostly due to the foreign reserve change in September (September: USD -15 billion; August: USD 3 billion). (Figures 2.15) Accordingly, foreign reserves decreased to USD 3,092.43 billion in September from USD 3,107.18 billion in August. (Figure 2.16)

Altogether, we believe the capital outflow is still manageable: first, the RMB appreciation after the Phase One deal in October will support the capital inflows; second, the PBoC still has implemented tight capital control, avoiding a large scale of capital flight; third, the PBoC in this round of RMB depreciation has not intervened the RMB by burning foreign reserve as what it did in the aftermath of 811 RMB reform in 2015. Thus, the capital outflows, although expanded in September, are expected to be still manageable in the rest of the year.

The RMB to USD exchange rate has experienced a roller-coaster up-and-down in Q3. On August 5th, the PBoC allowed the RMB to USD exchange rate exceeding the important psychological level of 7 for the first time since 2008, amid the renewed escalation of the China-US trade war due to Trump’s latest tariff hike. The psychological level of 7.0 has been broken in both onshore and offshore market. The market widely believes that it is the retaliated method by the PBoC to respond Trump’s tariff imposing. The currency depreciation beyond 7 implied that Chinese policymakers will take a tougher stance to react to Trump's tariff threat. Actually, in the past, China's authorities painstakingly kept the currency stable so as to alleviate Trump's critique of currency manipulation.

After the PBoC allowed the RMB to USD exchange rate plunging beyond 7 in early August, the RMB has been in a fast depreciation trend from August to early October until most recently the trade war achieved the Phase One deal progress. The RMB exchange rate experienced a rally by 1.1% accumulatively right after the China-US Phase One deal was announced in the second week of October as the talk has raised prospects of the Phase One deal that could include a currency pact. In the rest of this year, we believe that the RMB to USD exchange heavily will depend on the China-US trade talk progress. (Figure 2.14)

According to the US side, the currency pact with China may be similar to the proposed United States-Mexico- Canada Agreement (USMCA), including refraining from currency devaluations to seek trade advantage and also increases transparency of information sharing about government foreign exchange operations such as currency market interventions. More importantly, the currency pact term, which is anticipated widely in the market that Trump, might request China to appreciate RMB to the pre-trade war level (6.8-6.9 around).

Capital outflows accelerated but still manageable

Thanks to the authorities’ tenacious efforts to push for the opening of China’s domestic capital market, China’s equity and bond market was included in MSCI Emerging market Index and Bloomberg-Barclay Index in the first quarter of this year. It means that many passive investors around the world have to increase their exposure to China’s capital market so as to benchmark their portfolio to these Index. Such a positive shift has resulted in a considerable size of capital inflows over the past few months.

However, given that the trade war has still unsettled, before the Phase One deal in October, the RMB depreciation expectation still dominated capital outflows. Based on our capital outflow estimation model, the September capital outflow reached RMB 57.18 billion, larger than the August’s outflow of RMB 33.29 billion. The accelerating capital outflow is mostly due to the foreign reserve change in September (September: USD -15 billion; August: USD 3 billion). (Figures 2.15) Accordingly, foreign reserves decreased to USD 3,092.43 billion in September from USD 3,107.18 billion in August. (Figure 2.16)

Altogether, we believe the capital outflow is still manageable: first, the RMB appreciation after the Phase One deal in October will support the capital inflows; second, the PBoC still has implemented tight capital control, avoiding a large scale of capital flight; third, the PBoC in this round of RMB depreciation has not intervened the RMB by burning foreign reserve as what it did in the aftermath of 811 RMB reform in 2015. Thus, the capital outflows, although expanded in September, are expected to be still manageable in the rest of the year.

3. Lingering trade tensions weigh on medium-long term growth outlook

Downward revision to our growth projections

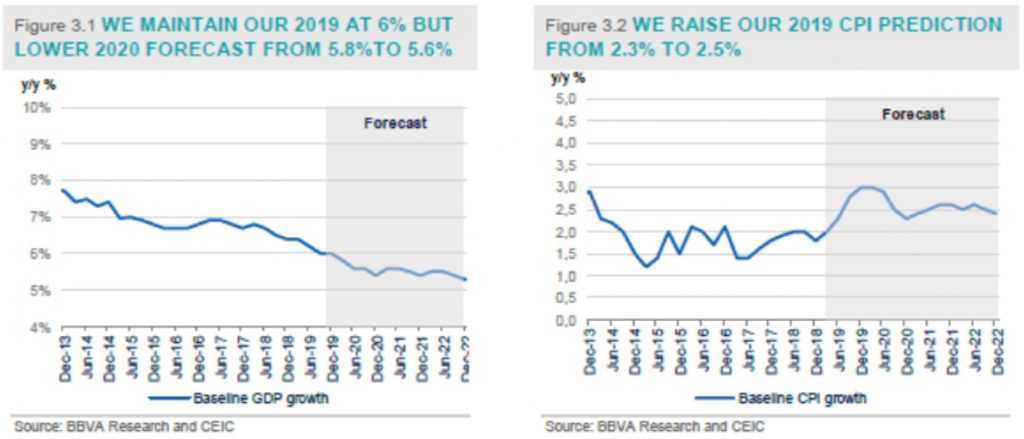

In the Q3 China Economic Outlook published in July, we concluded that the prospect of China’s economy hinges on the development of trade talks with the US. We believe this conclusion is still tenable and update our growth projections based on the progress of trade talks. In particular, we maintain our baseline growth projection at 6% for 2019 while lower our 2020 projection to 5.6% from 5.8%. The Q3 GDP outturn could have brought some upward bias to our 2019 full-year growth projection of 6%. Nevertheless, the mounting pressure emanating from trade tensions with the US as well as some domestic fragility such as massive debt pile make us hold a relatively pessimistic view toward the growth performance in the last quarter.

After the breakup of bilateral trade negotiation in early May, the relation between two sides entered into a negative spiral until recently they decided to pursue a partial agreement first and leave the thorny part of negotiation to the next phases. At the high level US-China trade talks held in second week of October, the delegates from China and the US confirmed that they are close to sign a phase-one agreement to defuse escalated hostility.

The content of the deal hasn’t been disclosed yet. Based on relevant news reports, we expect the phase-one deal to include below elements: (i) a currency pact to address the US concern of the RMB competitive depreciation; (ii) Chinese commitment to substantially increase purchases of US agricultural products up to the level of USD 40-50 bn per year; and (iii) the US suspension of tariff hike from 25% to 30% which was slated to be effective on Oct 15.

However, uncertainties still abound in the way ahead. More importantly, as we discussed in our Q3 China Economic Outlook, the souring trade relation between the US have already done irreversible damage to China’s economy. The longer the deadlock of the trade talks continues the greater damage we are going to see. The wrestling between these two sides over the past three months indicate that there is a long way to cover for them to solve all the trade problems.

What’s next for trade talks?

As claimed by President Trump, he is anticipating signing the phase-one agreement in November when he and President Xi are to meet at the APAC conference in Chile. However, Steven Mnuchin, the US Treasury secretary, has warned that a new round of tariffs set for December 15th on USD156 billion of Chinese goods would be triggered if China failed to seal the deal. He also highlighted the fragility of the truce reached last week.

The future phases of negotiations are still full of uncertainties:

First, US-China trade talk will become more politicized as Trump will use it as a tool to win his 2020 US president election. Thus, Trump’s stance might be more hardened on China. Second, compared with the Phase One deal which includes some issues that are easier to solve, the future phases of the deals have more difficult items to negotiate, such as technology transfer, China’s structural reform and SOE subsidies etc. Third, China has also become more assertive on many trade related issues. China's domestic propaganda machine has been mobilized to criticize the US over the past couple of months. Any significant concession to the US could incur domestic criticism. More importantly, China's authorities are fully aware of the risk that Trump might not successfully secure his second president term. As such, China's leaders might be reluctant to use their own political capital to reach a transitory deal with the current US administration in short term.

Altogether, the October Phase One deal seems to make the US-China trade negotiation from “bilateral tariff imposing” scenario to a “deal” track, which is a good turnaround among the previous months of deadlock. However, both sides are aware that the Phase One deal does not suggest the quick end of the trade war at all. There are still full of uncertainties in the future phases of negotiations. Meanwhile, China will closely watch the development of US domestic politics and adjust their strategy on an ongoing basis. China might even accept certain intermittent solution to deliberately prolong the process. For the positive side, China could proactively and voluntarily tiptoe toward some US requests of market opening and intellectual property protection since China's authorities accept the notion that these measures are also in China's own interest in the long run. Self-propelled reforms in these aspects will also help to minimize domestic pressure once a trade deal is made with the US.

The PBoC set LPR as the new monetary policy benchmark rate

The most important move from monetary policy side in Q3 is the PBoC announced to replace its benchmark lending rate with a more market-driven Loan Prime Rate (LPR) as the new monetary policy benchmark rate on August 19th, indicating a finalization of a long-awaited interest rate liberalization reform: a combination of the previous “dual-track” interest rate systems into “one-track” system. (Monetary Policy: New Framework, New Stance and Putting the final piece into the new monetary policy framework: timing is the key)

The new LPR pricing system will obviously weaken the role of the previous benchmark rate set by the central bank by delegating the price-setting power to the 18 chosen banks. Under the new system, a club of 18 lenders selected by the PBoC will submit their LPR quote, the lowest rate offered to their best clients, to the central bank on a monthly basis. The LPR pricing formula is equal to the one-year medium-term lending facility (a rate that is viewed as being closer to market rates for credit) plus some adding points (depending on banks’ risk premium, cost of funds etc.) The central bank will then calculate the average of those rates and publish it at 9:30 am on the 20th of every month, as the benchmark rate for the whole banking industry to follow. In addition, banks have been told by the PBOC that the LPR must be used in all new loan agreements – a major change from the existing practice where all loan contracts use the official benchmark rate.

Developing the LPR as the new monetary benchmark rate is a welcome move as well as a significant milestone for China’s interest rate liberalization reform and the improvement of new monetary policy “corridor” system. But some caveats are still noteworthy: there are still some obstacles ahead for full-on interest rate liberalization in China, for instance, the PBoC will probably remain involved in the LPR pricing for now, in order to safeguard the transition and prevent potential spikes in interest rate volatility. In addition, it will be quite challenging for Chinese banks’ balance sheet management and risk control, and also for their profit margin under the new LPR pricing mechanism.

From now on we therefore shift our forecast target from the previous one-year lending rate to the LPR. The LPR was recently reduced to 4.2% on September 20th from the previous reading at 4.25% in August, indicating the second time of interest rate cut under the new LPR scheme (the first time is to cut LPR from previous 4.35% to 4.25%). We predict that the PBoC will cut LPR every month by 0.05% in October and November, to continue to stimulate economic growth. Together with the two cuts in August and September, the LPR will be reduced to 4.1% at end of this year. And it will be further cut for two times (0.05% each) to 4% in end-2020.

More fiscal and monetary easing measures are expected to offset growth headwinds

On the policy front, China’s authorities have already deployed a flurry of monetary and fiscal easing initiatives to offset domestic and external headwinds since the second half of 2018.

From the monetary policy perspective, except for the LPR reform analyzed in the last section, other monetary easing measures include: two RRR cuts this year (in January and September respectively) and initiatives to support Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) financing, etc.

In particular, in the future, the authorities could consider applying certain regulatory forbearance to incentivize banks to extend credit to the real economy. Moreover, the authorities can help banks to replenish their capital so as to increase their capacity to absorb loss relating to the lending to SMEs.

On the fiscal policy front, the authorities are leaning more heavily on fiscal stimulus in this round of stimulation. It has announced tax cuts package of nearly 2 trillion yuan (USD 290.83 billion) on both corporate and personal income and a quota of 2.15 trillion yuan for special bond issuance by local governments for infrastructure projects. The government also allowed local government special bonds to be used as equity for projects and planned to issue Special Construction Bond (SCB) to support infrastructure investment etc.

However, Chinese policymakers have repeatedly vowed not to open the credit floodgates in an economy already saddled with piles of debt - a legacy of massive stimulus during the global financial crisis in 2008-09 and subsequent downturns. But after stabilizing in 2018, debt is on the rise again as the government ramps up stimulus. Thus, the policy room of both monetary and fiscal policy is not that big, as the authorities don’t want to over-stimulate the economy through debt borrowing which could add long-term risks to China’s financial stability.

Inflation pressure is manageable despite of the run-up of pork prices

In the second half of 2019, CPI has been rallying mainly as the food-prices rebound significantly from the previous level due to the outbreak of African Swine Fever (ASF) in China. In particular, September pork price increased by 69.3% y/y, while it increased by 21.3% y/y for January to September as a whole. Aggregately, in Q3, CPI growth rocked to 2.9%, compared with the average of 2.2% in 1H.

However, we believe that the general price level is still manageable from the following perspectives: First, in the recently announced Phase One deal with the US, China will buy a large amount of pork from the US, which will have downward pressure on pork price domestically. Second, based on the Phase One deal, China and the US will sign a currency pact, which refraining China from currency devaluations to seek trade advantage and also increases transparency of information sharing about government foreign exchange operations such as currency market interventions. That means, the appreciation pressure of RMB will maintain domestic CPI at a contained level. Third, the announced cuts in VAT and other tax at the first half this year will have downward pressure on general price level. Finally, the deceleration of Production Price Index (PPI), currently at the -1.2% y/y growth rate, could offset the food price run-up as the industrial related prices declined. There could be pass-through effects from the weak PPI to non-food prices as Chinese authorities have downplayed the previous de-leveraging campaign amid growth slowdown.

Altogether, we raise our CPI prediction of this year from 2.3% previously to 2.5% and maintain 2.5% forecast for 2020 (Bloomberg consensus: 2019: 2.5% and 2020: 2.3%). (Figure 3.2)

3. Lingering trade tensions weigh on medium-long term growth outlook

Downward revision to our growth projections

In the Q3 China Economic Outlook published in July, we concluded that the prospect of China’s economy hinges on the development of trade talks with the US. We believe this conclusion is still tenable and update our growth projections based on the progress of trade talks. In particular, we maintain our baseline growth projection at 6% for 2019 while lower our 2020 projection to 5.6% from 5.8%. The Q3 GDP outturn could have brought some upward bias to our 2019 full-year growth projection of 6%. Nevertheless, the mounting pressure emanating from trade tensions with the US as well as some domestic fragility such as massive debt pile make us hold a relatively pessimistic view toward the growth performance in the last quarter.

After the breakup of bilateral trade negotiation in early May, the relation between two sides entered into a negative spiral until recently they decided to pursue a partial agreement first and leave the thorny part of negotiation to the next phases. At the high level US-China trade talks held in second week of October, the delegates from China and the US confirmed that they are close to sign a phase-one agreement to defuse escalated hostility.

The content of the deal hasn’t been disclosed yet. Based on relevant news reports, we expect the phase-one deal to include below elements: (i) a currency pact to address the US concern of the RMB competitive depreciation; (ii) Chinese commitment to substantially increase purchases of US agricultural products up to the level of USD 40-50 bn per year; and (iii) the US suspension of tariff hike from 25% to 30% which was slated to be effective on Oct 15.

However, uncertainties still abound in the way ahead. More importantly, as we discussed in our Q3 China Economic Outlook, the souring trade relation between the US have already done irreversible damage to China’s economy. The longer the deadlock of the trade talks continues the greater damage we are going to see. The wrestling between these two sides over the past three months indicate that there is a long way to cover for them to solve all the trade problems.

What’s next for trade talks?

As claimed by President Trump, he is anticipating signing the phase-one agreement in November when he and President Xi are to meet at the APAC conference in Chile. However, Steven Mnuchin, the US Treasury secretary, has warned that a new round of tariffs set for December 15th on USD156 billion of Chinese goods would be triggered if China failed to seal the deal. He also highlighted the fragility of the truce reached last week.

The future phases of negotiations are still full of uncertainties:

First, US-China trade talk will become more politicized as Trump will use it as a tool to win his 2020 US president election. Thus, Trump’s stance might be more hardened on China. Second, compared with the Phase One deal which includes some issues that are easier to solve, the future phases of the deals have more difficult items to negotiate, such as technology transfer, China’s structural reform and SOE subsidies etc. Third, China has also become more assertive on many trade related issues. China's domestic propaganda machine has been mobilized to criticize the US over the past couple of months. Any significant concession to the US could incur domestic criticism. More importantly, China's authorities are fully aware of the risk that Trump might not successfully secure his second president term. As such, China's leaders might be reluctant to use their own political capital to reach a transitory deal with the current US administration in short term.

Altogether, the October Phase One deal seems to make the US-China trade negotiation from “bilateral tariff imposing” scenario to a “deal” track, which is a good turnaround among the previous months of deadlock. However, both sides are aware that the Phase One deal does not suggest the quick end of the trade war at all. There are still full of uncertainties in the future phases of negotiations. Meanwhile, China will closely watch the development of US domestic politics and adjust their strategy on an ongoing basis. China might even accept certain intermittent solution to deliberately prolong the process. For the positive side, China could proactively and voluntarily tiptoe toward some US requests of market opening and intellectual property protection since China's authorities accept the notion that these measures are also in China's own interest in the long run. Self-propelled reforms in these aspects will also help to minimize domestic pressure once a trade deal is made with the US.

The PBoC set LPR as the new monetary policy benchmark rate

The most important move from monetary policy side in Q3 is the PBoC announced to replace its benchmark lending rate with a more market-driven Loan Prime Rate (LPR) as the new monetary policy benchmark rate on August 19th, indicating a finalization of a long-awaited interest rate liberalization reform: a combination of the previous “dual-track” interest rate systems into “one-track” system. (Monetary Policy: New Framework, New Stance and Putting the final piece into the new monetary policy framework: timing is the key)

The new LPR pricing system will obviously weaken the role of the previous benchmark rate set by the central bank by delegating the price-setting power to the 18 chosen banks. Under the new system, a club of 18 lenders selected by the PBoC will submit their LPR quote, the lowest rate offered to their best clients, to the central bank on a monthly basis. The LPR pricing formula is equal to the one-year medium-term lending facility (a rate that is viewed as being closer to market rates for credit) plus some adding points (depending on banks’ risk premium, cost of funds etc.) The central bank will then calculate the average of those rates and publish it at 9:30 am on the 20th of every month, as the benchmark rate for the whole banking industry to follow. In addition, banks have been told by the PBOC that the LPR must be used in all new loan agreements – a major change from the existing practice where all loan contracts use the official benchmark rate.

Developing the LPR as the new monetary benchmark rate is a welcome move as well as a significant milestone for China’s interest rate liberalization reform and the improvement of new monetary policy “corridor” system. But some caveats are still noteworthy: there are still some obstacles ahead for full-on interest rate liberalization in China, for instance, the PBoC will probably remain involved in the LPR pricing for now, in order to safeguard the transition and prevent potential spikes in interest rate volatility. In addition, it will be quite challenging for Chinese banks’ balance sheet management and risk control, and also for their profit margin under the new LPR pricing mechanism.

From now on we therefore shift our forecast target from the previous one-year lending rate to the LPR. The LPR was recently reduced to 4.2% on September 20th from the previous reading at 4.25% in August, indicating the second time of interest rate cut under the new LPR scheme (the first time is to cut LPR from previous 4.35% to 4.25%). We predict that the PBoC will cut LPR every month by 0.05% in October and November, to continue to stimulate economic growth. Together with the two cuts in August and September, the LPR will be reduced to 4.1% at end of this year. And it will be further cut for two times (0.05% each) to 4% in end-2020.

More fiscal and monetary easing measures are expected to offset growth headwinds

On the policy front, China’s authorities have already deployed a flurry of monetary and fiscal easing initiatives to offset domestic and external headwinds since the second half of 2018.

From the monetary policy perspective, except for the LPR reform analyzed in the last section, other monetary easing measures include: two RRR cuts this year (in January and September respectively) and initiatives to support Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) financing, etc.

In particular, in the future, the authorities could consider applying certain regulatory forbearance to incentivize banks to extend credit to the real economy. Moreover, the authorities can help banks to replenish their capital so as to increase their capacity to absorb loss relating to the lending to SMEs.

On the fiscal policy front, the authorities are leaning more heavily on fiscal stimulus in this round of stimulation. It has announced tax cuts package of nearly 2 trillion yuan (USD 290.83 billion) on both corporate and personal income and a quota of 2.15 trillion yuan for special bond issuance by local governments for infrastructure projects. The government also allowed local government special bonds to be used as equity for projects and planned to issue Special Construction Bond (SCB) to support infrastructure investment etc.

However, Chinese policymakers have repeatedly vowed not to open the credit floodgates in an economy already saddled with piles of debt - a legacy of massive stimulus during the global financial crisis in 2008-09 and subsequent downturns. But after stabilizing in 2018, debt is on the rise again as the government ramps up stimulus. Thus, the policy room of both monetary and fiscal policy is not that big, as the authorities don’t want to over-stimulate the economy through debt borrowing which could add long-term risks to China’s financial stability.

Inflation pressure is manageable despite of the run-up of pork prices

In the second half of 2019, CPI has been rallying mainly as the food-prices rebound significantly from the previous level due to the outbreak of African Swine Fever (ASF) in China. In particular, September pork price increased by 69.3% y/y, while it increased by 21.3% y/y for January to September as a whole. Aggregately, in Q3, CPI growth rocked to 2.9%, compared with the average of 2.2% in 1H.

However, we believe that the general price level is still manageable from the following perspectives: First, in the recently announced Phase One deal with the US, China will buy a large amount of pork from the US, which will have downward pressure on pork price domestically. Second, based on the Phase One deal, China and the US will sign a currency pact, which refraining China from currency devaluations to seek trade advantage and also increases transparency of information sharing about government foreign exchange operations such as currency market interventions. That means, the appreciation pressure of RMB will maintain domestic CPI at a contained level. Third, the announced cuts in VAT and other tax at the first half this year will have downward pressure on general price level. Finally, the deceleration of Production Price Index (PPI), currently at the -1.2% y/y growth rate, could offset the food price run-up as the industrial related prices declined. There could be pass-through effects from the weak PPI to non-food prices as Chinese authorities have downplayed the previous de-leveraging campaign amid growth slowdown.

Altogether, we raise our CPI prediction of this year from 2.3% previously to 2.5% and maintain 2.5% forecast for 2020 (Bloomberg consensus: 2019: 2.5% and 2020: 2.3%). (Figure 3.2)

The potential US-China currency pact raises prospects of the RMB

Amid the unsettled China-US trade war, the short-term RMB to USD exchange rate is dominated by the trade talk progress. Recently, the RMB exchange rate rallied significantly right after the new round of US-China trade talk achieved some success in the second week of October as the talk has raised prospects of the Phase One deal that could include a currency pact.

According to the US side, the currency pact with China may be similar to the proposed United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), including refraining from currency devaluations to seek trade advantage and also increases transparency of information sharing about government foreign exchange operations such as currency market interventions. More importantly, the currency pact term, which is anticipated widely in the market that Trump, might request China to appreciate RMB to the pre-trade war level (6.8 around).

The new progress of the last week trade talk might add some upside risk to our previous forecasting to RMB exchange rate that it will depreciate to 7.2 at end-2019. Actually, the RMB to USD exchange rate has appreciated significantly by 1.1% accumulatively from its regional peak at 7.17 to 7.06 after the Phase One deal announced. Thus, given the good progress of China-US Phase One deal, we revised our RMB to USD exchange rate prediction at end of this year from 7.2 to 7 and forecast end-2020 RMB exchange rate at 6.8 in our baseline scenario.

In the medium to long term, the prospective combination of “deficit current account” and “two-way fluctuation of capital account” in the future makes it challenging for the PBoC to maintain RMB exchange rate stability. The shrinking of current account, mainly led by a declining trade surplus, together with a fluctuating capital account, will give more uncertainties to China’s foreign reserve. (See our Economic Watch: China | When its current account turns deficit…)

4. Risks are still to the downside

Despite a slew of growth-boosting measures since 2H of the last year, the world’s second-largest economy has yet to stabilize. That explains why most economists remain sober about China’s growth outlook as demand at home and abroad weakens.

The unsettled trade war between the US and China remains the prime risk throughout 2019 and 2020. Even if it might be solved phase by phase in the future, a tech war between the US and China will last for a longer time. Other possible risks include the rising leverage of local government debt and corporate debt due to the current round easing monetary and fiscal measures. Moreover, Hong Kong’s violent demonstration is also a threat to Chinese growth and its relationship with the US.

First, the unsettled trade war remains the prime risk for growth. As discussed in the previous section, although the US and China are now entering into a “deal” track from “bilateral tariff imposing”, uncertainties of the future phases of deal still exist. Firstly, US-China trade talk will become more politicized as Trump will use it as a tool to win his 2020 US president election. Secondly, compared with the Phase One deal which includes some issues that are easier to solve, the future phases of the deals have more difficult items to negotiate, such as technology transfer, China’s structural reform and SOE subsidies etc. Thirdly, China has also become more assertive on many trade related issues. Any significant concession to the US could incur domestic criticism. More importantly, China's authorities are fully aware of the risk that Trump might not successfully secure his second president term thus China's leaders might be reluctant to use their own political capital to reach a transitory deal with the current US administration in short term.

The trade tensions could also spread to other areas and lead to more confrontations in high-tech sector, financial system and even geopolitics. Altogether, all uncertainties surrounding the trade issue between China and the US could have significant impact on market sentiments, asset prices and economic growth.

Second, the easing monetary and fiscal measures to offset the growth slowdown starting from 2H 2018 might lead to debt overhang problem again. According to the BIS statistic, Chinese overall Adjusted Credit to the Nonfinancial Sector to GDP ratio became 259.4% in Q1 2019, increasing significantly from its stabilizing ratio of 241.5 % in 2017. The Washington-based Institute of International Finance (IIF) also estimated that in the first quarter of 2019, the total amount of corporate, household and government debt in China hit an eye-watering 303% of GDP. Although the authorities have said time and again that its borrowings are manageable, but policy levers are hampered by the risk that choking off further debt could accelerate the slowing of economic growth that is already underway. It remains a challenge for the authorities to strike a balance between stabilizing the debt level and stimulating growth.

Third, demonstration in Hong Kong is also a big threat to Chinese economic and financial stability as well as its relations with the US. Public unrest in the global financial center Hong Kong has been going on for more than four months. It began with the aim to oppose powers which could have seen Hong Kong authorities extradite fugitives to mainland China, but has now morphed into wider demands from citizens who want property reform and fear the strengthening hand of mainland China. Violence and loud protest have horrified onlookers and it seems there is little chance that Hong Kong government has the voice to quell the anger. Moreover, the US lawmakers recentlyt have supported Hong Kong protesters by passing a Human Rights and Democracy Act aimed at upholding human rights in the city, which makes the China-US relation more complicated although the two sides are on the way to reach the Phase One trade deal.

The potential US-China currency pact raises prospects of the RMB

Amid the unsettled China-US trade war, the short-term RMB to USD exchange rate is dominated by the trade talk progress. Recently, the RMB exchange rate rallied significantly right after the new round of US-China trade talk achieved some success in the second week of October as the talk has raised prospects of the Phase One deal that could include a currency pact.

According to the US side, the currency pact with China may be similar to the proposed United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), including refraining from currency devaluations to seek trade advantage and also increases transparency of information sharing about government foreign exchange operations such as currency market interventions. More importantly, the currency pact term, which is anticipated widely in the market that Trump, might request China to appreciate RMB to the pre-trade war level (6.8 around).

The new progress of the last week trade talk might add some upside risk to our previous forecasting to RMB exchange rate that it will depreciate to 7.2 at end-2019. Actually, the RMB to USD exchange rate has appreciated significantly by 1.1% accumulatively from its regional peak at 7.17 to 7.06 after the Phase One deal announced. Thus, given the good progress of China-US Phase One deal, we revised our RMB to USD exchange rate prediction at end of this year from 7.2 to 7 and forecast end-2020 RMB exchange rate at 6.8 in our baseline scenario.

In the medium to long term, the prospective combination of “deficit current account” and “two-way fluctuation of capital account” in the future makes it challenging for the PBoC to maintain RMB exchange rate stability. The shrinking of current account, mainly led by a declining trade surplus, together with a fluctuating capital account, will give more uncertainties to China’s foreign reserve. (See our Economic Watch: China | When its current account turns deficit…)

4. Risks are still to the downside

Despite a slew of growth-boosting measures since 2H of the last year, the world’s second-largest economy has yet to stabilize. That explains why most economists remain sober about China’s growth outlook as demand at home and abroad weakens.

The unsettled trade war between the US and China remains the prime risk throughout 2019 and 2020. Even if it might be solved phase by phase in the future, a tech war between the US and China will last for a longer time. Other possible risks include the rising leverage of local government debt and corporate debt due to the current round easing monetary and fiscal measures. Moreover, Hong Kong’s violent demonstration is also a threat to Chinese growth and its relationship with the US.

First, the unsettled trade war remains the prime risk for growth. As discussed in the previous section, although the US and China are now entering into a “deal” track from “bilateral tariff imposing”, uncertainties of the future phases of deal still exist. Firstly, US-China trade talk will become more politicized as Trump will use it as a tool to win his 2020 US president election. Secondly, compared with the Phase One deal which includes some issues that are easier to solve, the future phases of the deals have more difficult items to negotiate, such as technology transfer, China’s structural reform and SOE subsidies etc. Thirdly, China has also become more assertive on many trade related issues. Any significant concession to the US could incur domestic criticism. More importantly, China's authorities are fully aware of the risk that Trump might not successfully secure his second president term thus China's leaders might be reluctant to use their own political capital to reach a transitory deal with the current US administration in short term.

The trade tensions could also spread to other areas and lead to more confrontations in high-tech sector, financial system and even geopolitics. Altogether, all uncertainties surrounding the trade issue between China and the US could have significant impact on market sentiments, asset prices and economic growth.

Second, the easing monetary and fiscal measures to offset the growth slowdown starting from 2H 2018 might lead to debt overhang problem again. According to the BIS statistic, Chinese overall Adjusted Credit to the Nonfinancial Sector to GDP ratio became 259.4% in Q1 2019, increasing significantly from its stabilizing ratio of 241.5 % in 2017. The Washington-based Institute of International Finance (IIF) also estimated that in the first quarter of 2019, the total amount of corporate, household and government debt in China hit an eye-watering 303% of GDP. Although the authorities have said time and again that its borrowings are manageable, but policy levers are hampered by the risk that choking off further debt could accelerate the slowing of economic growth that is already underway. It remains a challenge for the authorities to strike a balance between stabilizing the debt level and stimulating growth.

Third, demonstration in Hong Kong is also a big threat to Chinese economic and financial stability as well as its relations with the US. Public unrest in the global financial center Hong Kong has been going on for more than four months. It began with the aim to oppose powers which could have seen Hong Kong authorities extradite fugitives to mainland China, but has now morphed into wider demands from citizens who want property reform and fear the strengthening hand of mainland China. Violence and loud protest have horrified onlookers and it seems there is little chance that Hong Kong government has the voice to quell the anger. Moreover, the US lawmakers recentlyt have supported Hong Kong protesters by passing a Human Rights and Democracy Act aimed at upholding human rights in the city, which makes the China-US relation more complicated although the two sides are on the way to reach the Phase One trade deal.