Dong Jinyue and Xia Le: China's Financial Liberalization–Time to Restart

2018-05-28 IMI RMB exchange rate reform: still missing the final jump

RMB exchange rate liberalization has been suspended for quite a while after a failed RMB exchange rate reform in August 11, 2015. Originally, the authorities planned to push forward RMB exchange rate marketization by allowing the next day’s RMB fixing price equal to the previous day’s closing price. However, the authorities did not expect the over-reaction of the financial market to the reform, which eventually led to a sharp RMB depreciation and a large-scale of FX market turmoil which spill-over to domestic stock market and other countries’ stock and FX markets etc.

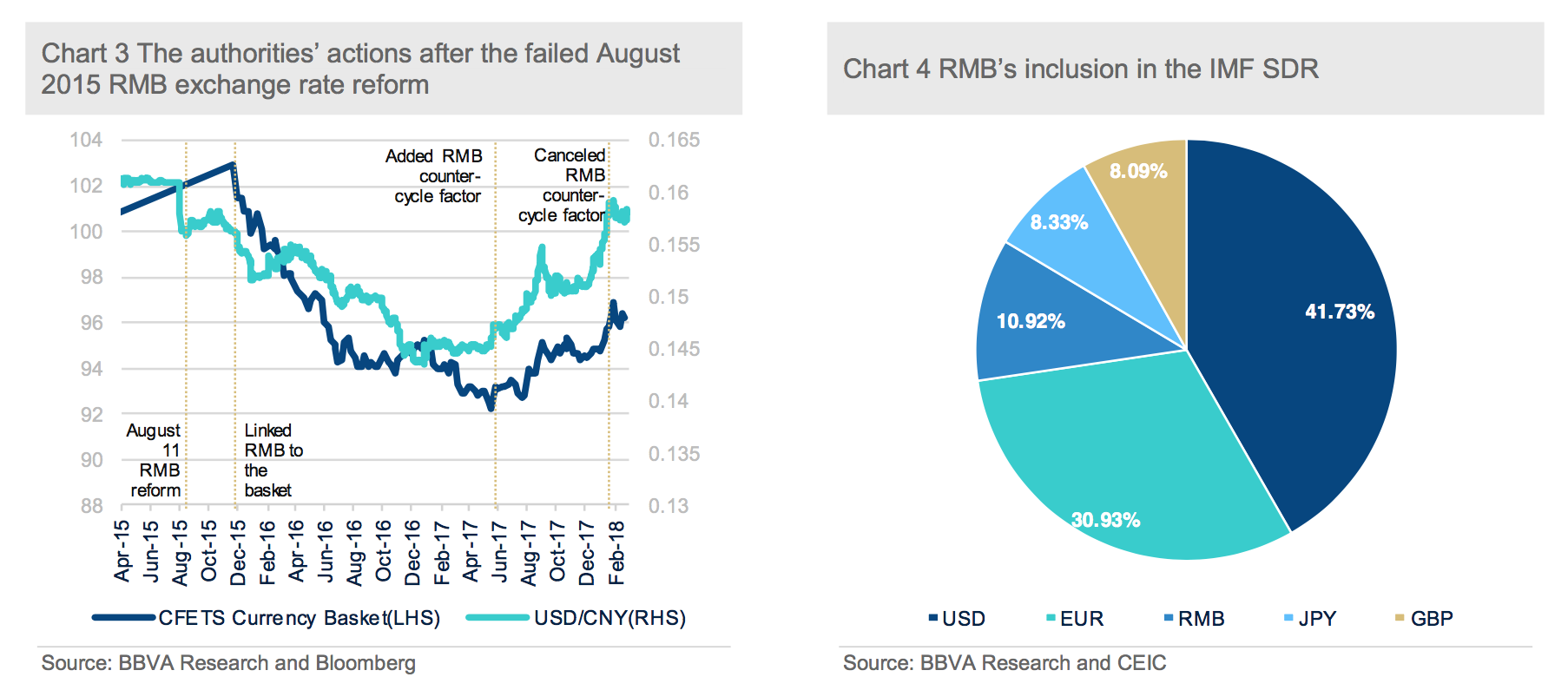

In front of the financial turmoil after August 2015, the authorities adopted a series of measures to stabilize the market and rebuild global investors’ confidence on RMB exchange rate. After some market intervention to stabilize the dipping RMB exchange rate, the authorities re-linked RMB exchange rate to the RMB basket at end-2015. In addition, the authorities also introduced counter-cycle factors into the RMB pricing scheme in mid-2017, in a bid to further stabilize the RMB exchange rate.

RMB exchange rate reform: still missing the final jump

RMB exchange rate liberalization has been suspended for quite a while after a failed RMB exchange rate reform in August 11, 2015. Originally, the authorities planned to push forward RMB exchange rate marketization by allowing the next day’s RMB fixing price equal to the previous day’s closing price. However, the authorities did not expect the over-reaction of the financial market to the reform, which eventually led to a sharp RMB depreciation and a large-scale of FX market turmoil which spill-over to domestic stock market and other countries’ stock and FX markets etc.

In front of the financial turmoil after August 2015, the authorities adopted a series of measures to stabilize the market and rebuild global investors’ confidence on RMB exchange rate. After some market intervention to stabilize the dipping RMB exchange rate, the authorities re-linked RMB exchange rate to the RMB basket at end-2015. In addition, the authorities also introduced counter-cycle factors into the RMB pricing scheme in mid-2017, in a bid to further stabilize the RMB exchange rate.

After China’s economy successfully engineered a recovery in 2017, the pressure on currency depreciation has largely alleviated if not evaporated entirely. The authorities have accordingly reduced their intervention in the FX market. The PBoC has recently stated that it hasn’t intervened into the exchange rate for more than a year.

Although it’s hard to prove the validity of the PBoC’s statement, the central bank took out the counter-cycle factors in determining its daily mid-price of the RMB in early 2018. (Chart 3) The liberalization of the exchange rate seems to be back on the authorities’ agenda.

We forecast that the final stage of the exchange rate liberalization will be the “Clean Float”, which is likely to happen after China’s domestic financial system completes its deleveraging and regains its healthiness. That being said, the authorities could allow the exchange rate to float before 2020. (Chart 4) In this respect, the IMF’s next periodical review of the SDR, which is scheduled at 2021, will give China’s authorities more incentive to make the final jump before it.

Capital account liberalization: more programs on the way

Capital account opening also achieved some new development. Regarding the stock market opening-up, thanks to the joint efforts of China and the UK, preparatory work for Shanghai-London Stock Connect is proceeding as desired, which will be launched this year. To further improve the stock market connectivity of the Chinese mainland and Hong Kong, the PBoC will increase the daily quota by three times from May 1, after which the daily quota for Shanghai-bound and Shenzhen-bound investment will be increased from RMB 13 billion to RMB 52 billion, while that for Hong Kong-bound investment from RMB 10.5 billion to RMB 42 billion.

The expansion of the daily limit in connected programs particularly caters to the demand of the Chinese A-share inclusion by MSCI, a global provider of research-based indexes and analytics announced that it will include 234 China A Large Cap shares in the MSCI Emerging Markets Index from June 1st 2018. It is expected to bring additional capital inflows to Chinese A share market equivalent to around RMB 100bn in 2018 after many international passive investors are tracking MSCI index.

Together with the expansion of stock connect programs, the authorities have also increased the quota for Qualified Foreign Institutional Investors (QFII) Qualified Domestic Institutional Investors (QDII) and Renminbi Qualified Foreign Institutional Investors (RQFII). For instance, till end-2017, there have been 18 countries or regions received the RQFII quota, with the total amount of RMB 1.74 trillion, RMB 76.6 billion increasing from the year of 2016. In particular, both QFII and RQFII have been an important channel for overseas investors to invest in the Mainland financial markets while QDII the other way round. With the expansion of the quota of these schemes, it indicates the authorities’ strategy of gradual opening capital account with cautions, which prompts the progress of financial liberalization.

In addition, China’s financial center Shanghai has resumed an outbound investment scheme, called Qualified Domestic Limited Partnership (QDLP) after a two-year hiatus, granting licenses to about a dozen global money managers. It signals that the authorities are less worried about capital outflows amid an appreciating RMB exchange rate. Foreign fund managers with newly awarded quotas will be able to raise money in China for investment overseas under the QDLP plan for the first time since late 2015.This quota-based scheme was unofficially suspended when China tightened capital controls amid turmoil in its stock and currency markets since 2015. In April 2018, the State Administration of Foreign Exchange boosted the QDLP and Qualified Domestic Investment Enterprise (QDIE) trial programs in the two cities to $5 billion each. SAFE raised the quota from $2 billion for the QDLP program in Shanghai and $2.5 billion for QDIE in Shenzhen. These moves indicate that Chinese authorities have stepped up efforts to grow the two-way flow of both inbound and outbound investments in their on-going effort to further liberalize China’s financial markets and open up China’s capital account.

It is noted that all these above programs relating to capital account liberalization have certain quotas or limits so that the authorities can better deal with potential stress scenarios. Moreover, the authorities seem to be aggressive in pushing for the programs which are able to bring new capital inflows such as QFII, RQFII while remain very cautious about the ones that could lead to capital outflows. That being said, the authorities have taking a measured approach in reopening its capital account so as to avert the repeat of financial turmoil seen in 2015-2016.

Further opening-up of financial sector

Amid the pressure from the US trade war threat, President Xi Jinping in his speech at the 17th Boao Forum, announced plans to further open China’s economy. Correspondingly, the newly appointed PBoC governor Yi Gang promulgated the details and timetable of the opening-up policies in financial sector in the Boao Forum for Asia in April 2018.

The following measures will be implemented in the following several months of this year:

· Remove the foreign ownership cap for banks and asset management companies, treating domestic and foreign capital equally; allow foreign banks to set up branches and subsidiaries at the same time.

· Lift the foreign ownership cap to 51% for securities companies, fund managers, futures companies, and life insurers, and remove the cap in three years.

· No longer require joint-funded securities companies to have at least one local securities company as a shareholder.

· Allow eligible foreign investors to provide insurance agent and loss adjuster services in China.

· Lift restrictions on the business scope of foreign-invested insurance brokerage companies, treating them as equals of domestic companies.

In addition, the PBoC will roll out the following measures within this year:

· Encourage foreign ownership in trust, financial leasing, auto finance, currency brokerage and consumer finance.

· Apply no cap to foreign ownership in financial asset investment companies and wealth management companies newly established by commercial banks.

· Substantially expand the business scope of foreign banks.

· Remove restrictions on the business scope of jointly-funded securities companies, treating domestic and foreign institutions equally.

· Foreign insurance companies will no longer need to have a representative office in China for two consecutive years prior to establishing a fully-owned institution.

Although the official list of reforms is quite long, covering items ranging from relaxing foreign ownership in financial institutions to substantially expanding the business scope of foreign banks, most of the reforms had already been announced during President Trump’s visit to China last November or were scheduled to have been fulfilled after China’s entry to the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001. That means, amid the pressure from the US, China determined to honor promises step by step to liberalize its financial sector. As described by Yi Gang, China’s new central banker, it is “a prudent, cautious, gradualist move” for the financial sector opening-up reform.

Actually, right after the announcement of the above financial sector opening-up policies, some foreign investment banks have already applied the license of operation in the mainland China. Meanwhile, some other previously announced financial sector opening-up measures have been implemented smoothly. For instance, the authorities have lifted market access limit for bank card clearing institutions and non-bank payment institutions, eased restrictions on rating services provided by foreign financial service companies, and granted national treatment to foreign credit information companies.

Is this time different?

Although the restart of China’s financial liberalization has sent an encouraging signal, the market still held the concern about whether the new momentum is sustainable enough. To a certain extent, such questions make sense because China has repeatedly promised financial opening and reforms over the last decade but the real progress has thus far been limited. Some people even question that the Chinese authorities have no real intention to push forward real reforms but want to pay lip service this time.

We have a more optimistic view in this respect. This time could be different because both external pressure and domestic need will force the authorities to advance financial liberalization and make the real breakthroughs. After witnessing several episodes of financial turmoil during 2015-2016, the authorities are well aware that structural reforms in the financial sector are the best solution to systemic risks in the long run. For example, only a market- determined interest rate could allure people to withdraw money from the shadow banking activities and redeposit them into the formal banking sector. Moreover, a flexible exchange rate will enhance rather than weaken the country’s capacity to absorb unexpected external shocks. Of course all these reforms need to proceed with a measured approach.

Meanwhile, the authorities have also felt the urgency to honor their promise to the WTO and open China’s financial market so as to create a benign external environment. Although the US is now waving a stick of “trade war” at the front, other advanced economies also have a lot of complaints against China’s delayed process of opening its domestic financial market. From a strategic perspective, it is in China’s own interest to accelerate financial market opening to win over more friends in defense of the US attack to the country’s export sector.

Nevertheless, some domestic and external factors could also exert adverse impact on the momentum in financial liberalization and even slow its progress. Now China is pushing forward a campaign of financial deleveraging with the aim to reduce debt level of both financial and corporate sectors. If the deleveraging process goes smoothly, financial liberalization could accelerate as well. In contrast, if the deleveraging led to the escalation of domestic risks for the short run, the authorities will likely slow down the process of financial liberalization for stability consideration.

The trade war risk with the US also has its sophisticated impact on financial liberalization process. Although the threat of trade war can give the authorities more incentives to maintain the momentum of financial liberalization, a full-blown trade war, albeit not in our base scenario, will adversely affect China’s economy and elevate domestic financial risks. In that case, the authorities might sacrifice financial liberalization again to maintain the stability of domestic financial sector.

After China’s economy successfully engineered a recovery in 2017, the pressure on currency depreciation has largely alleviated if not evaporated entirely. The authorities have accordingly reduced their intervention in the FX market. The PBoC has recently stated that it hasn’t intervened into the exchange rate for more than a year.

Although it’s hard to prove the validity of the PBoC’s statement, the central bank took out the counter-cycle factors in determining its daily mid-price of the RMB in early 2018. (Chart 3) The liberalization of the exchange rate seems to be back on the authorities’ agenda.

We forecast that the final stage of the exchange rate liberalization will be the “Clean Float”, which is likely to happen after China’s domestic financial system completes its deleveraging and regains its healthiness. That being said, the authorities could allow the exchange rate to float before 2020. (Chart 4) In this respect, the IMF’s next periodical review of the SDR, which is scheduled at 2021, will give China’s authorities more incentive to make the final jump before it.

Capital account liberalization: more programs on the way

Capital account opening also achieved some new development. Regarding the stock market opening-up, thanks to the joint efforts of China and the UK, preparatory work for Shanghai-London Stock Connect is proceeding as desired, which will be launched this year. To further improve the stock market connectivity of the Chinese mainland and Hong Kong, the PBoC will increase the daily quota by three times from May 1, after which the daily quota for Shanghai-bound and Shenzhen-bound investment will be increased from RMB 13 billion to RMB 52 billion, while that for Hong Kong-bound investment from RMB 10.5 billion to RMB 42 billion.

The expansion of the daily limit in connected programs particularly caters to the demand of the Chinese A-share inclusion by MSCI, a global provider of research-based indexes and analytics announced that it will include 234 China A Large Cap shares in the MSCI Emerging Markets Index from June 1st 2018. It is expected to bring additional capital inflows to Chinese A share market equivalent to around RMB 100bn in 2018 after many international passive investors are tracking MSCI index.

Together with the expansion of stock connect programs, the authorities have also increased the quota for Qualified Foreign Institutional Investors (QFII) Qualified Domestic Institutional Investors (QDII) and Renminbi Qualified Foreign Institutional Investors (RQFII). For instance, till end-2017, there have been 18 countries or regions received the RQFII quota, with the total amount of RMB 1.74 trillion, RMB 76.6 billion increasing from the year of 2016. In particular, both QFII and RQFII have been an important channel for overseas investors to invest in the Mainland financial markets while QDII the other way round. With the expansion of the quota of these schemes, it indicates the authorities’ strategy of gradual opening capital account with cautions, which prompts the progress of financial liberalization.

In addition, China’s financial center Shanghai has resumed an outbound investment scheme, called Qualified Domestic Limited Partnership (QDLP) after a two-year hiatus, granting licenses to about a dozen global money managers. It signals that the authorities are less worried about capital outflows amid an appreciating RMB exchange rate. Foreign fund managers with newly awarded quotas will be able to raise money in China for investment overseas under the QDLP plan for the first time since late 2015.This quota-based scheme was unofficially suspended when China tightened capital controls amid turmoil in its stock and currency markets since 2015. In April 2018, the State Administration of Foreign Exchange boosted the QDLP and Qualified Domestic Investment Enterprise (QDIE) trial programs in the two cities to $5 billion each. SAFE raised the quota from $2 billion for the QDLP program in Shanghai and $2.5 billion for QDIE in Shenzhen. These moves indicate that Chinese authorities have stepped up efforts to grow the two-way flow of both inbound and outbound investments in their on-going effort to further liberalize China’s financial markets and open up China’s capital account.

It is noted that all these above programs relating to capital account liberalization have certain quotas or limits so that the authorities can better deal with potential stress scenarios. Moreover, the authorities seem to be aggressive in pushing for the programs which are able to bring new capital inflows such as QFII, RQFII while remain very cautious about the ones that could lead to capital outflows. That being said, the authorities have taking a measured approach in reopening its capital account so as to avert the repeat of financial turmoil seen in 2015-2016.

Further opening-up of financial sector

Amid the pressure from the US trade war threat, President Xi Jinping in his speech at the 17th Boao Forum, announced plans to further open China’s economy. Correspondingly, the newly appointed PBoC governor Yi Gang promulgated the details and timetable of the opening-up policies in financial sector in the Boao Forum for Asia in April 2018.

The following measures will be implemented in the following several months of this year:

· Remove the foreign ownership cap for banks and asset management companies, treating domestic and foreign capital equally; allow foreign banks to set up branches and subsidiaries at the same time.

· Lift the foreign ownership cap to 51% for securities companies, fund managers, futures companies, and life insurers, and remove the cap in three years.

· No longer require joint-funded securities companies to have at least one local securities company as a shareholder.

· Allow eligible foreign investors to provide insurance agent and loss adjuster services in China.

· Lift restrictions on the business scope of foreign-invested insurance brokerage companies, treating them as equals of domestic companies.

In addition, the PBoC will roll out the following measures within this year:

· Encourage foreign ownership in trust, financial leasing, auto finance, currency brokerage and consumer finance.

· Apply no cap to foreign ownership in financial asset investment companies and wealth management companies newly established by commercial banks.

· Substantially expand the business scope of foreign banks.

· Remove restrictions on the business scope of jointly-funded securities companies, treating domestic and foreign institutions equally.

· Foreign insurance companies will no longer need to have a representative office in China for two consecutive years prior to establishing a fully-owned institution.

Although the official list of reforms is quite long, covering items ranging from relaxing foreign ownership in financial institutions to substantially expanding the business scope of foreign banks, most of the reforms had already been announced during President Trump’s visit to China last November or were scheduled to have been fulfilled after China’s entry to the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001. That means, amid the pressure from the US, China determined to honor promises step by step to liberalize its financial sector. As described by Yi Gang, China’s new central banker, it is “a prudent, cautious, gradualist move” for the financial sector opening-up reform.

Actually, right after the announcement of the above financial sector opening-up policies, some foreign investment banks have already applied the license of operation in the mainland China. Meanwhile, some other previously announced financial sector opening-up measures have been implemented smoothly. For instance, the authorities have lifted market access limit for bank card clearing institutions and non-bank payment institutions, eased restrictions on rating services provided by foreign financial service companies, and granted national treatment to foreign credit information companies.

Is this time different?

Although the restart of China’s financial liberalization has sent an encouraging signal, the market still held the concern about whether the new momentum is sustainable enough. To a certain extent, such questions make sense because China has repeatedly promised financial opening and reforms over the last decade but the real progress has thus far been limited. Some people even question that the Chinese authorities have no real intention to push forward real reforms but want to pay lip service this time.

We have a more optimistic view in this respect. This time could be different because both external pressure and domestic need will force the authorities to advance financial liberalization and make the real breakthroughs. After witnessing several episodes of financial turmoil during 2015-2016, the authorities are well aware that structural reforms in the financial sector are the best solution to systemic risks in the long run. For example, only a market- determined interest rate could allure people to withdraw money from the shadow banking activities and redeposit them into the formal banking sector. Moreover, a flexible exchange rate will enhance rather than weaken the country’s capacity to absorb unexpected external shocks. Of course all these reforms need to proceed with a measured approach.

Meanwhile, the authorities have also felt the urgency to honor their promise to the WTO and open China’s financial market so as to create a benign external environment. Although the US is now waving a stick of “trade war” at the front, other advanced economies also have a lot of complaints against China’s delayed process of opening its domestic financial market. From a strategic perspective, it is in China’s own interest to accelerate financial market opening to win over more friends in defense of the US attack to the country’s export sector.

Nevertheless, some domestic and external factors could also exert adverse impact on the momentum in financial liberalization and even slow its progress. Now China is pushing forward a campaign of financial deleveraging with the aim to reduce debt level of both financial and corporate sectors. If the deleveraging process goes smoothly, financial liberalization could accelerate as well. In contrast, if the deleveraging led to the escalation of domestic risks for the short run, the authorities will likely slow down the process of financial liberalization for stability consideration.

The trade war risk with the US also has its sophisticated impact on financial liberalization process. Although the threat of trade war can give the authorities more incentives to maintain the momentum of financial liberalization, a full-blown trade war, albeit not in our base scenario, will adversely affect China’s economy and elevate domestic financial risks. In that case, the authorities might sacrifice financial liberalization again to maintain the stability of domestic financial sector.