Dong Jinyue and Xia Le: LPR: China's Market-based "Policy" Rate

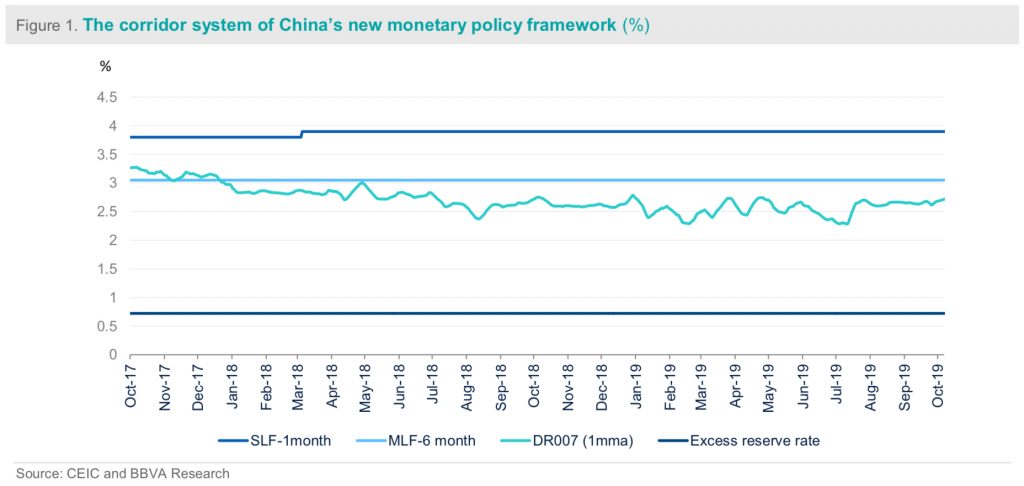

2019-11-07 IMI The “dual-track” policy rate system has certain inherent problems. Commercial banks could be insensitive to the change of DR007 as a chunk of their loans and deposit products still based on the benchmark interest rates. As a result, it could hamstring the central bank’s policy loosening. For instance, the PBoC started to ease monetary policy in the second of 2018 while the growth of both total social financing and new yuan loans remained anaemic over the same period. (Figure 2) Moreover, the weighted average lending rate in the economy remained stubbornly high even though the authorities have manged to press DR007 down to a lower level. (Figure 3)

Thus, by eliminating the previous benchmark lending rate and designating LPR as a new reference interest rate, the central bank aims to improve the monetary policy transmission.

The “dual-track” policy rate system has certain inherent problems. Commercial banks could be insensitive to the change of DR007 as a chunk of their loans and deposit products still based on the benchmark interest rates. As a result, it could hamstring the central bank’s policy loosening. For instance, the PBoC started to ease monetary policy in the second of 2018 while the growth of both total social financing and new yuan loans remained anaemic over the same period. (Figure 2) Moreover, the weighted average lending rate in the economy remained stubbornly high even though the authorities have manged to press DR007 down to a lower level. (Figure 3)

Thus, by eliminating the previous benchmark lending rate and designating LPR as a new reference interest rate, the central bank aims to improve the monetary policy transmission.

How does the new LPR pricing system function?

The new LPR pricing system is a market based one which delegates the price-setting power to the 18 designated banks. These 18 lenders are required to submit their loan prime rates (LPR), the lowest rate offered to their best clients, to the central bank on a monthly basis. Apart from the big Chinese banks, the group of lenders also includes foreign banks (only Citi Group and Standard Chartered), rural commercial banks, and city commercial banks.

More importantly, the PBoC artificially linked the LPR with the rate of one-year medium-term lending facilities (MLF) by setting a uniform LPR pricing formula for all 18 designated banks. The MLF is the PBoC’s facilities through which the central bank injects liquidity into the money market with maturities from three-month to one-year. The 18 lenders determine their adding points in the formula based on their risk premium, cost of funds etc.

Loan Prime Rate (LPR) for individual bank= one year medium-term lending facility (MLF) + adding points (1)

After obtaining all 18 lenders’ quotes for LPR the central bank will then calculate the average of those rates and publish it at 9:30 am on the 20th of every month, as the reference rate for the entire banking industry to follow. In addition, banks have been told by the PBOC that the LPR must be used in all new loan agreements – a major change from the existing practice where all loan contracts use the official benchmark lending rate.

The meanings of the LPR reform are multi-faceted

First, the move was expected to make Chinese monetary policy transmission mechanism smoother by combining the previous “dual-track” interest rate systems into “one-track”.

Under the previous monetary policy framework, it is difficult for monetary policy transmitted from the money market rate to the credit market rate. Thus, we often observed a combination of low monetary market rate (such as DR007 etc.) and a high lending rate in the credit market. The reason is that unlike the banking system in Europe or the US, the deposit, instead of the interbank borrowing from the money market, is the main funding source of Chinese commercial banks. Thus, the reduction of money market rate might not influence commercial banks’ lending rates that much.

Now the new mechanism makes it easier for the changes of interbank market rates in the money market to flow to the real economy in the credit market as the monetary transmission becomes “from monetary policy rate to LPR to lending rate”, instead of the previous “from benchmark lending rate to lending rate”. Thus, by linking interbank rate to LPR, the PBoC is trying to solve the previous monetary policy transmission problem under the old “dual-track” monetary framework.

Second, the move will effectively lower the market interest rates amid growth slowdown and unsettled China-US trade war. The benchmark lending rate under the old regime was 4.35%, while the one-year medium-term lending facility (MLF), to which the new LPR will be linked, was 3.3%. Together with the adding points in the formula (1), the new LPR was set to be 4.25% in August, 0.1% lower than the previous benchmark lending rate, indicating an effective interest rate cut. In any case, since policymakers are keen to lower the funding cost in the real economy, we believe both the LPR and average loan rate will probably drop modestly after the new mechanism starts.

Forecasting the future LPR

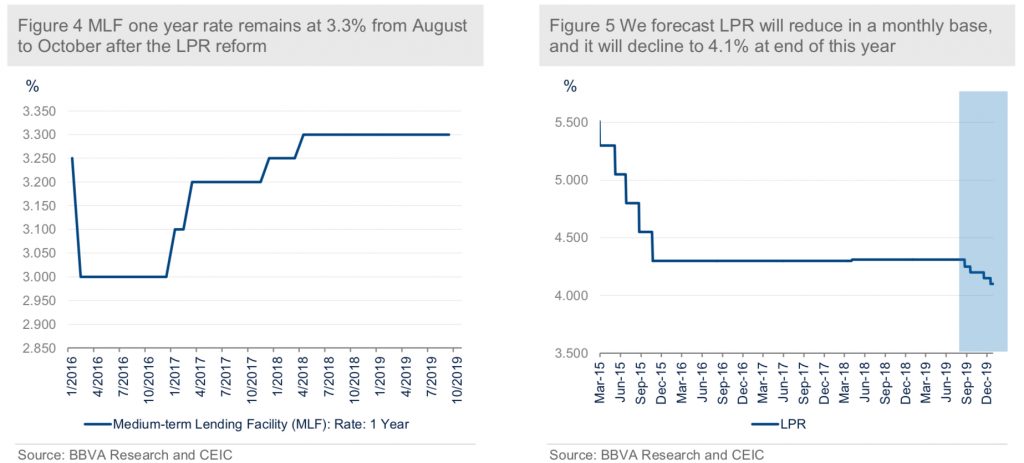

Given that the new monetary target rate LPR pricing formula by individual bank becomes MLF plus some adding points, intuitively, the prediction of future LPR becomes mostly the forecasting of MLF. However, at the beginning of the new LPR scheme, the one-year MLF remained same level at 3.3% from August to October, while LPR dipped from previously 4.31% to 4.2%. This indicates the PBoC’s intention to cut interest rate by lowering the “adding points” term instead of MLF at the beginning of the transformation. (Figure 4)

After the LPR reform in August, the path of LPR cut by the PBoC is: from 4.31% to 4.25% in August; from 4.25% to 4.2% in September; no LPR cut in October.

How does the new LPR pricing system function?

The new LPR pricing system is a market based one which delegates the price-setting power to the 18 designated banks. These 18 lenders are required to submit their loan prime rates (LPR), the lowest rate offered to their best clients, to the central bank on a monthly basis. Apart from the big Chinese banks, the group of lenders also includes foreign banks (only Citi Group and Standard Chartered), rural commercial banks, and city commercial banks.

More importantly, the PBoC artificially linked the LPR with the rate of one-year medium-term lending facilities (MLF) by setting a uniform LPR pricing formula for all 18 designated banks. The MLF is the PBoC’s facilities through which the central bank injects liquidity into the money market with maturities from three-month to one-year. The 18 lenders determine their adding points in the formula based on their risk premium, cost of funds etc.

Loan Prime Rate (LPR) for individual bank= one year medium-term lending facility (MLF) + adding points (1)

After obtaining all 18 lenders’ quotes for LPR the central bank will then calculate the average of those rates and publish it at 9:30 am on the 20th of every month, as the reference rate for the entire banking industry to follow. In addition, banks have been told by the PBOC that the LPR must be used in all new loan agreements – a major change from the existing practice where all loan contracts use the official benchmark lending rate.

The meanings of the LPR reform are multi-faceted

First, the move was expected to make Chinese monetary policy transmission mechanism smoother by combining the previous “dual-track” interest rate systems into “one-track”.

Under the previous monetary policy framework, it is difficult for monetary policy transmitted from the money market rate to the credit market rate. Thus, we often observed a combination of low monetary market rate (such as DR007 etc.) and a high lending rate in the credit market. The reason is that unlike the banking system in Europe or the US, the deposit, instead of the interbank borrowing from the money market, is the main funding source of Chinese commercial banks. Thus, the reduction of money market rate might not influence commercial banks’ lending rates that much.

Now the new mechanism makes it easier for the changes of interbank market rates in the money market to flow to the real economy in the credit market as the monetary transmission becomes “from monetary policy rate to LPR to lending rate”, instead of the previous “from benchmark lending rate to lending rate”. Thus, by linking interbank rate to LPR, the PBoC is trying to solve the previous monetary policy transmission problem under the old “dual-track” monetary framework.

Second, the move will effectively lower the market interest rates amid growth slowdown and unsettled China-US trade war. The benchmark lending rate under the old regime was 4.35%, while the one-year medium-term lending facility (MLF), to which the new LPR will be linked, was 3.3%. Together with the adding points in the formula (1), the new LPR was set to be 4.25% in August, 0.1% lower than the previous benchmark lending rate, indicating an effective interest rate cut. In any case, since policymakers are keen to lower the funding cost in the real economy, we believe both the LPR and average loan rate will probably drop modestly after the new mechanism starts.

Forecasting the future LPR

Given that the new monetary target rate LPR pricing formula by individual bank becomes MLF plus some adding points, intuitively, the prediction of future LPR becomes mostly the forecasting of MLF. However, at the beginning of the new LPR scheme, the one-year MLF remained same level at 3.3% from August to October, while LPR dipped from previously 4.31% to 4.2%. This indicates the PBoC’s intention to cut interest rate by lowering the “adding points” term instead of MLF at the beginning of the transformation. (Figure 4)

After the LPR reform in August, the path of LPR cut by the PBoC is: from 4.31% to 4.25% in August; from 4.25% to 4.2% in September; no LPR cut in October.

The future path of LPR cut will be more balanced. On the one hand, the economic growth slowdown, together with the US FED interest rate cut calls for further LPR cuts. On the other hand, as the authorities do not want to fill the economy with a flood of debt like what they did in the 2008 global financial crisis, the step of reducing LPR will not be that fast. The good progress of China-US talk, especially the achievement of Phase One deal in October, will also lower the PBoC’s intention of a fast LPR cut. In addition, the currency pact in the Phase One deal, by refraining China from currency devaluations to seek trade advantage will trigger a RMB appreciation, which puts pressure on a fast interest rate cut. Actually, after the two LPR cuts in August and September respectively, the PBoC chose to maintain LPR at 4.2% in October 20th, sending the signal of a slower step of LPR cut.

In the final two months of this year, we predict the LPR will be reduced by 0.05% every month. That means, at end of this year, the LPR will reduce to 4.1%. And we forecast LPR at end-2020 will be reduced to 3.9%. (Figure 5)

Some caveats are still noteworthy

Altogether, developing the LPR as the new monetary reference rate in August is a welcome move. It is a significant milestone for China’s interest rate liberalization reform and helps to improve the new monetary policy “corridor” system. However, some caveats are still noteworthy:

First, changing to LPR scheme might not indicate the full interest rate liberalization in China as there are still some obstacles ahead for full interest rate liberalization. For instance, the PBoC will probably remain involved in the LPR pricing for the current transition period, in order to safeguard the transition and prevent potential spikes in interest rate volatility.

In particular, as Chinese commercial banks always have motivations to report their LPR with upside bias in order to have higher interest rate margin, the PBoC might have to window guidance their LPR pricing formula (especially the adding points part) and may also regulate a range for adding points pricing in the future. If this situation materializes, it indicates the PBoC still has pricing power for the LPR.

Second, it will be quite challenging for Chinese banks’ balance sheet management. As the PBoC’s tension is to reduce the market lending rate in initiating the LPR reform this time, given that banks always are competing to increase their deposit rate to attract depositors, banks’ profit margin under the new LPR pricing mechanism might be shrink significantly. Thus, how to transit the lending rate cut to deposit rate reducing will be another challenge for commercial banks.

Third, it is notoriously difficult for a central bank to stimulate the economy by easing monetary policy, even though the new LPR pricing system tries to link the credit market rate with the money market rate. In retrospect to the previous economic downturns, both the US and Euro zone were unable to use traditional monetary policy tools to put the growth back on track and therefore chose to implement some unconventional monetary policy tools including quantitative easing, forward guidance, negative interest rate, TLTRO etc.

Indeed, a more relevant problem to the policy transmission is banks’ aggravated risk appetite in the face of increasing growth headwinds. The clampdown of shadow banking activities has forcefully driven a lot of borrowers out of the credit market and led to growth slowdown. The still unsolved trade war with the US not only stalls the export sector but also hits consumers and producers’ confidence. At such a juncture, banks’ concerns over asset quality may override the authorities’ efforts of policy easing so that these risk-averse banks are reluctant to transmit the lower financing costs to their clients thus choose not to expand their lending to the real economy.

The future path of LPR cut will be more balanced. On the one hand, the economic growth slowdown, together with the US FED interest rate cut calls for further LPR cuts. On the other hand, as the authorities do not want to fill the economy with a flood of debt like what they did in the 2008 global financial crisis, the step of reducing LPR will not be that fast. The good progress of China-US talk, especially the achievement of Phase One deal in October, will also lower the PBoC’s intention of a fast LPR cut. In addition, the currency pact in the Phase One deal, by refraining China from currency devaluations to seek trade advantage will trigger a RMB appreciation, which puts pressure on a fast interest rate cut. Actually, after the two LPR cuts in August and September respectively, the PBoC chose to maintain LPR at 4.2% in October 20th, sending the signal of a slower step of LPR cut.

In the final two months of this year, we predict the LPR will be reduced by 0.05% every month. That means, at end of this year, the LPR will reduce to 4.1%. And we forecast LPR at end-2020 will be reduced to 3.9%. (Figure 5)

Some caveats are still noteworthy

Altogether, developing the LPR as the new monetary reference rate in August is a welcome move. It is a significant milestone for China’s interest rate liberalization reform and helps to improve the new monetary policy “corridor” system. However, some caveats are still noteworthy:

First, changing to LPR scheme might not indicate the full interest rate liberalization in China as there are still some obstacles ahead for full interest rate liberalization. For instance, the PBoC will probably remain involved in the LPR pricing for the current transition period, in order to safeguard the transition and prevent potential spikes in interest rate volatility.

In particular, as Chinese commercial banks always have motivations to report their LPR with upside bias in order to have higher interest rate margin, the PBoC might have to window guidance their LPR pricing formula (especially the adding points part) and may also regulate a range for adding points pricing in the future. If this situation materializes, it indicates the PBoC still has pricing power for the LPR.

Second, it will be quite challenging for Chinese banks’ balance sheet management. As the PBoC’s tension is to reduce the market lending rate in initiating the LPR reform this time, given that banks always are competing to increase their deposit rate to attract depositors, banks’ profit margin under the new LPR pricing mechanism might be shrink significantly. Thus, how to transit the lending rate cut to deposit rate reducing will be another challenge for commercial banks.

Third, it is notoriously difficult for a central bank to stimulate the economy by easing monetary policy, even though the new LPR pricing system tries to link the credit market rate with the money market rate. In retrospect to the previous economic downturns, both the US and Euro zone were unable to use traditional monetary policy tools to put the growth back on track and therefore chose to implement some unconventional monetary policy tools including quantitative easing, forward guidance, negative interest rate, TLTRO etc.

Indeed, a more relevant problem to the policy transmission is banks’ aggravated risk appetite in the face of increasing growth headwinds. The clampdown of shadow banking activities has forcefully driven a lot of borrowers out of the credit market and led to growth slowdown. The still unsolved trade war with the US not only stalls the export sector but also hits consumers and producers’ confidence. At such a juncture, banks’ concerns over asset quality may override the authorities’ efforts of policy easing so that these risk-averse banks are reluctant to transmit the lower financing costs to their clients thus choose not to expand their lending to the real economy.