Dong Jinyue and Xia Le: The Changing Role of RRR in New Monetary Policy Framework

2018-01-24 IMI The glorious history of the RRR

In mechanism, a RRR cut will lead to liquidity injection to the financial sector while a RRR hike will withdraw liquidity from the financial market. As such, the market interpreted RRR cuts as signals of monetary loosening and RRR hikes as signals of policy tightening. It is noted that the adjustment of the RRR doesn’t lead to the change in the central bank’s balance sheet, which is different from open market operation (OMO) or Quantitative Easing (QE), although they all function to manage the available liquidity in the financial sector.

RRR used to be an important monetary policy tool in China’s monetary framework. The frequency of its usage was higher than that of official policy rate. During the period of 2000-2017, the PBoC adjusted the RRR by 46 times while moved the policy interest rate by 26 times. The PBoC’s favoring of the RRR adjustment is well justified:

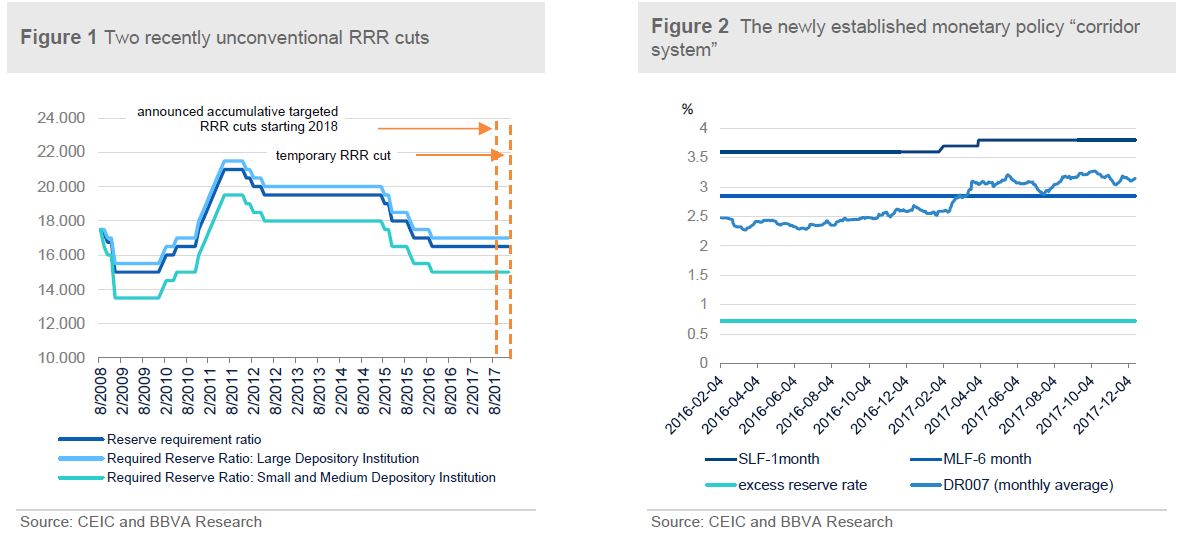

First, a large amount of SOEs were notoriously insensitive to the price signals in the credit market. On the contrary, the adjustment of available amount of credit, through liquidity management, has proved to be effective. Second, according to some scholars’ research, the adjustment of the RRR seems more granular than interest rate adjustment under certain circumstance. As a result, the PBoC preferred to use the RRR adjustment so as not to bring too large shocks to the financial market. Last but not least, during the most time between 1994 and the second half of 2013, China’s Balance of Payment (BOP) had twin surplus under both current and capital account. Therefore, the RRR adjustment can function as a sterilization tool for the central bank, which not only sent the signals of the authorities’ monetary policy stance but also helped the central bank to maintain the stability of exchange rate. (Figure 3)

All in all, under the previous monetary policy framework, RRR plays a dual role as both a monetary policy tool and liquidity management tool. More importantly, these two roles are not in conflict with each other given the persistently large-scale capital inflow and trade surplus.

The glorious history of the RRR

In mechanism, a RRR cut will lead to liquidity injection to the financial sector while a RRR hike will withdraw liquidity from the financial market. As such, the market interpreted RRR cuts as signals of monetary loosening and RRR hikes as signals of policy tightening. It is noted that the adjustment of the RRR doesn’t lead to the change in the central bank’s balance sheet, which is different from open market operation (OMO) or Quantitative Easing (QE), although they all function to manage the available liquidity in the financial sector.

RRR used to be an important monetary policy tool in China’s monetary framework. The frequency of its usage was higher than that of official policy rate. During the period of 2000-2017, the PBoC adjusted the RRR by 46 times while moved the policy interest rate by 26 times. The PBoC’s favoring of the RRR adjustment is well justified:

First, a large amount of SOEs were notoriously insensitive to the price signals in the credit market. On the contrary, the adjustment of available amount of credit, through liquidity management, has proved to be effective. Second, according to some scholars’ research, the adjustment of the RRR seems more granular than interest rate adjustment under certain circumstance. As a result, the PBoC preferred to use the RRR adjustment so as not to bring too large shocks to the financial market. Last but not least, during the most time between 1994 and the second half of 2013, China’s Balance of Payment (BOP) had twin surplus under both current and capital account. Therefore, the RRR adjustment can function as a sterilization tool for the central bank, which not only sent the signals of the authorities’ monetary policy stance but also helped the central bank to maintain the stability of exchange rate. (Figure 3)

All in all, under the previous monetary policy framework, RRR plays a dual role as both a monetary policy tool and liquidity management tool. More importantly, these two roles are not in conflict with each other given the persistently large-scale capital inflow and trade surplus.

New monetary policy framework calls for the change of the RRR’s role

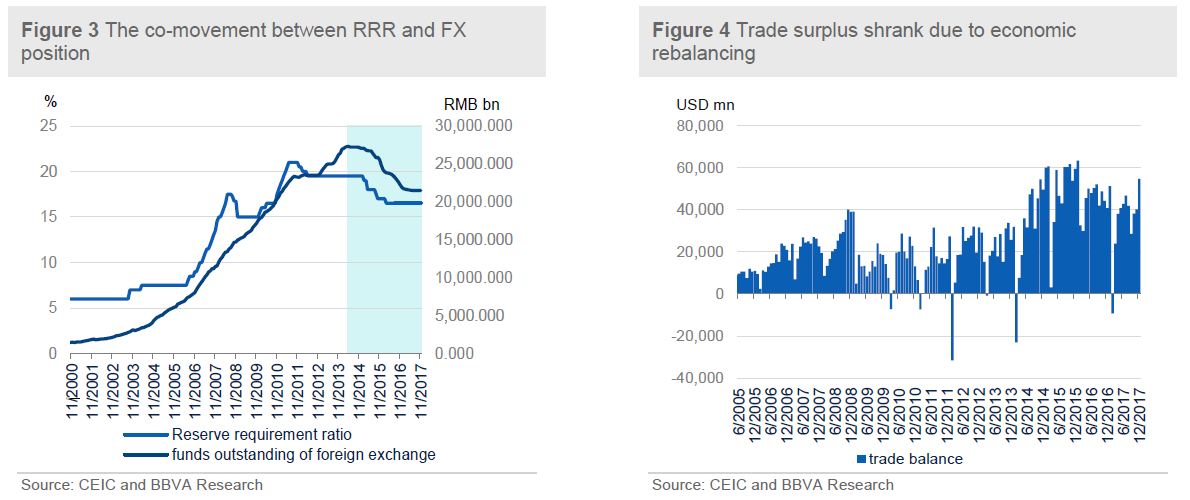

As China’s monetary policy framework is migrating to a new one centering on price tools, the role of the RRR is set to change. Such a process is also expedited by the change of the external environment. Starting from the second half of 2013 and especially after August 2015, the cross-border capital movement in China has turned net outflows compared to net inflows previously. At the same time, China’s trade surplus has gradually diminished over the past few years as the country’s economy is balanced towards domestic consumption. (Figure 4) As the BOP has become more balanced, the RRR’s additional function of sterilization seems redundant in terms of policy conduct.

Meanwhile, as the authorities’ primary target shifted to clamping down shadow banking activities and maintaining financial stability, the central bank needs to maintain a delicate balance of its monetary policy stance: on the one hand, they need to continue their regulatory tightening to squeeze the ballooning shadow banking sector while on the other hand find new ways to inject liquidity to the inter-bank market to maintain the market interest rate at a reasonable level and ensure the financial stability. Under such a circumstance, it is natural for PBoC to take the RRR as a pure tool of liquidity management. As we discussed in the previous section, the use of the RRR will not lead to the change in the size of the central bank’s balance sheet.

The PBoC is currently trying to transit from signaling the market by quantity tools (i.e. RRR adjustment) to price tools (by adjusting policy rate through the monetary “corridor system”) in the way of establishing the new monetary policy framework. Under such a “corridor system”, the movement of new policy rate target will be confined to a specific range, the “corridor”. In particular, the upper bound of the “corridor” are the interest rates of Standing Lending Facility (SLF) with the tenors of overnight, 7-day and 1-month, which are charged by the PBoC on short-term liquidity borrowing of qualified commercial banks. In addition to the SLF, the central bank has other liquidity injection tools with longer tenors of 3-month, 6-month and 1-year, namely the Medium-term Lending Facility (MLF). At the lower bound of the “corridor” is the interest rate which the central bank pays on banks’ excessive reserves. As such, banks can withdraw liquidity from the money market at the lower bound of the “corridor” when the money market interest rate falls below this level.

The new policy rate target is the pledged 7-day interbank market rate (DR007). As designed, the movement of the policy rate target should be effectively confined to the “corridor” because otherwise banks will directly go to the central bank for their liquidity borrowing (at the upper bound) or lending (at the lower bound). In the meantime, the central bank will frequently conduct open market operation (OMO) to align the policy rate target with policymakers’ desired level. Currently the main policy tools of OMO include 7-day, 14-day and 28-day repo (and reverse repo), which function to withdraw (or inject) liquidity from (into) the money market.

In practice, the PBoC also adopted several steps to foster the pledged 7-day repo rate as the new policy rate. For instance, in responding to the US FED interest rate hike in March, June and December respectively, the PBoC raised the reverse repo rate (which is the central bank open market operation rate) by 10 bps in March and 5 bps in December. Correspondingly, DR-007, which is deemed to be the policy rate, also increased significantly in March and December together with the increasing of the open market operation rate.

Still some challenges ahead…

However, some caveats are noteworthy in the change of the RRR’s role:

First, the PBoC might lose the ability to actively intervene the market liquidity if RRR decreases significantly, as sufficient reserve is the foundation for the central bank to conduct liquidity management; Second, banks’ capacity to withstand external shocks could deteriorate and even dampen investors’ confidence as lower RRRs means less cushion for financial market stability; and last but not least, a quick decreasing of RRR might give the market a wrong signal thus confuse the market that the PBoC is changing the monetary policy stance from tightening to easing, which is not consistent with the on-going financial deleveraging and macro-prudential management.

New monetary policy framework calls for the change of the RRR’s role

As China’s monetary policy framework is migrating to a new one centering on price tools, the role of the RRR is set to change. Such a process is also expedited by the change of the external environment. Starting from the second half of 2013 and especially after August 2015, the cross-border capital movement in China has turned net outflows compared to net inflows previously. At the same time, China’s trade surplus has gradually diminished over the past few years as the country’s economy is balanced towards domestic consumption. (Figure 4) As the BOP has become more balanced, the RRR’s additional function of sterilization seems redundant in terms of policy conduct.

Meanwhile, as the authorities’ primary target shifted to clamping down shadow banking activities and maintaining financial stability, the central bank needs to maintain a delicate balance of its monetary policy stance: on the one hand, they need to continue their regulatory tightening to squeeze the ballooning shadow banking sector while on the other hand find new ways to inject liquidity to the inter-bank market to maintain the market interest rate at a reasonable level and ensure the financial stability. Under such a circumstance, it is natural for PBoC to take the RRR as a pure tool of liquidity management. As we discussed in the previous section, the use of the RRR will not lead to the change in the size of the central bank’s balance sheet.

The PBoC is currently trying to transit from signaling the market by quantity tools (i.e. RRR adjustment) to price tools (by adjusting policy rate through the monetary “corridor system”) in the way of establishing the new monetary policy framework. Under such a “corridor system”, the movement of new policy rate target will be confined to a specific range, the “corridor”. In particular, the upper bound of the “corridor” are the interest rates of Standing Lending Facility (SLF) with the tenors of overnight, 7-day and 1-month, which are charged by the PBoC on short-term liquidity borrowing of qualified commercial banks. In addition to the SLF, the central bank has other liquidity injection tools with longer tenors of 3-month, 6-month and 1-year, namely the Medium-term Lending Facility (MLF). At the lower bound of the “corridor” is the interest rate which the central bank pays on banks’ excessive reserves. As such, banks can withdraw liquidity from the money market at the lower bound of the “corridor” when the money market interest rate falls below this level.

The new policy rate target is the pledged 7-day interbank market rate (DR007). As designed, the movement of the policy rate target should be effectively confined to the “corridor” because otherwise banks will directly go to the central bank for their liquidity borrowing (at the upper bound) or lending (at the lower bound). In the meantime, the central bank will frequently conduct open market operation (OMO) to align the policy rate target with policymakers’ desired level. Currently the main policy tools of OMO include 7-day, 14-day and 28-day repo (and reverse repo), which function to withdraw (or inject) liquidity from (into) the money market.

In practice, the PBoC also adopted several steps to foster the pledged 7-day repo rate as the new policy rate. For instance, in responding to the US FED interest rate hike in March, June and December respectively, the PBoC raised the reverse repo rate (which is the central bank open market operation rate) by 10 bps in March and 5 bps in December. Correspondingly, DR-007, which is deemed to be the policy rate, also increased significantly in March and December together with the increasing of the open market operation rate.

Still some challenges ahead…

However, some caveats are noteworthy in the change of the RRR’s role:

First, the PBoC might lose the ability to actively intervene the market liquidity if RRR decreases significantly, as sufficient reserve is the foundation for the central bank to conduct liquidity management; Second, banks’ capacity to withstand external shocks could deteriorate and even dampen investors’ confidence as lower RRRs means less cushion for financial market stability; and last but not least, a quick decreasing of RRR might give the market a wrong signal thus confuse the market that the PBoC is changing the monetary policy stance from tightening to easing, which is not consistent with the on-going financial deleveraging and macro-prudential management.