Betty Huang and Xia Le: China’s corporate sector: Deleveraging or re-leveraging?

2018-12-14 IMI …however, deleveraging efforts weighed on private enterprises

The deleveraging measures implemented by China’s authorities also have the side effect. The monetary tightening and clamp-down of shadow banking activities cut firms, in particular private and small ones, off credit supply which they used to live on; the strengthened control of SOEs and LGFV debt dampened economic activities and investment; the clean-up of zombie companies and overcapacity in certain industries led to more unemployment in the society. Worse is the unexpected escalation of US-China trade tensions in early 2018, which severely dampened the confidence of both investors and consumers.

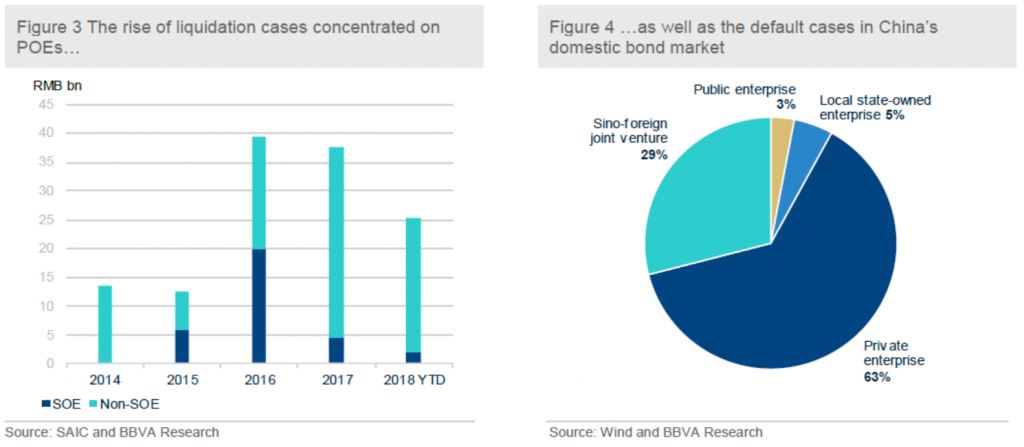

As a consequence, the private enterprises (POEs) in China bore the brunt of the deleveraging measures and escalating trade tensions with the US, due in part to the lack of the governmental support which are only applied to their SOE peers. The balance sheets of POEs deteriorated rapidly in 2018 (Figure 3 and 4)

…however, deleveraging efforts weighed on private enterprises

The deleveraging measures implemented by China’s authorities also have the side effect. The monetary tightening and clamp-down of shadow banking activities cut firms, in particular private and small ones, off credit supply which they used to live on; the strengthened control of SOEs and LGFV debt dampened economic activities and investment; the clean-up of zombie companies and overcapacity in certain industries led to more unemployment in the society. Worse is the unexpected escalation of US-China trade tensions in early 2018, which severely dampened the confidence of both investors and consumers.

As a consequence, the private enterprises (POEs) in China bore the brunt of the deleveraging measures and escalating trade tensions with the US, due in part to the lack of the governmental support which are only applied to their SOE peers. The balance sheets of POEs deteriorated rapidly in 2018 (Figure 3 and 4)

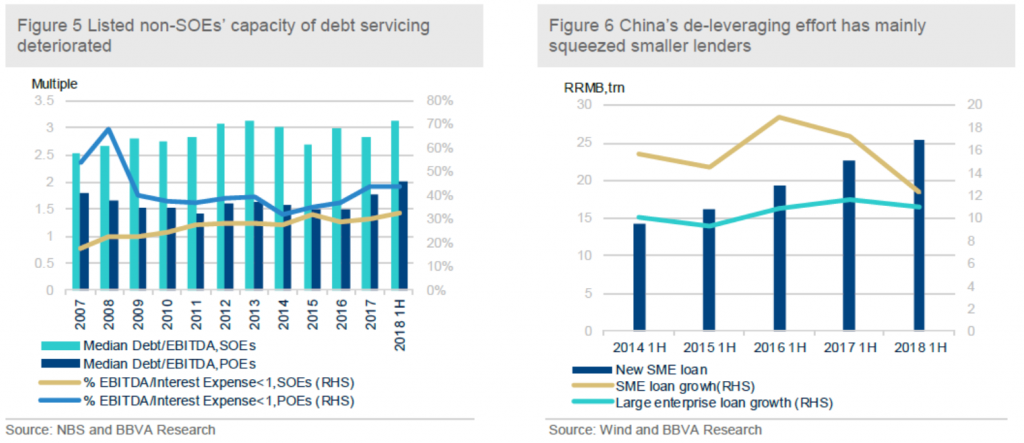

POEs’ disadvantages relative to SOEs through the deleverage campaign could also be found with listed firms. Based on the information contained in their financial statements, we have constructed two indicators to measure their indebtedness. (Figure 5) One is the ratio of Debt-to-EBITDA, which is a proxy of a firm’s debt level relative to its cash flow. The other is the ratio of EBITDA-to-Interest Expense, which gauges a firm’s capacity to service its interest-bearing debt. A natural threshold of this ratio is 1. A firm with its ratio of EBITDA-to-Interest Expense below this benchmark could have difficulty in servicing its debt. The median of Debt-to-EBITDA ratio among all listed non-SOEs rose in 2017 and the first half of 2018, suggesting that the non-SOEs failed to improve their balance sheets during the deleveraging campaign. The capacity of debt serving for listed non-SOEs also deteriorated in the first half of 2018 as the share of listed non-SOEs with an EBITDA-to-Interest Expense ratio below 1 increased from its level of 2017.

One prime reason why POEs failed to reduce their leverage is the clampdown of shadow banking activities whichhave cut them off funding channels and exposed them to great refinancing risk. At the same time, the formal banking sector was reluctant to increase their support for private enterprises due to both ever-increasing regulatory pressure and worsening economic outlook. As such, China’s deleveraging efforts have mainly squeezed smaller borrowers rather than well capitalized SOEs. Yearly growth of bank lending to small-medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), the majority of which are POEs, moderated to 12.2% in June 2018 from 17.2% a year ago. (Figure 6) Accordingly, the share of new bank lending to SMEs declined to 20.9% of total new corporate loans, a five-year low.

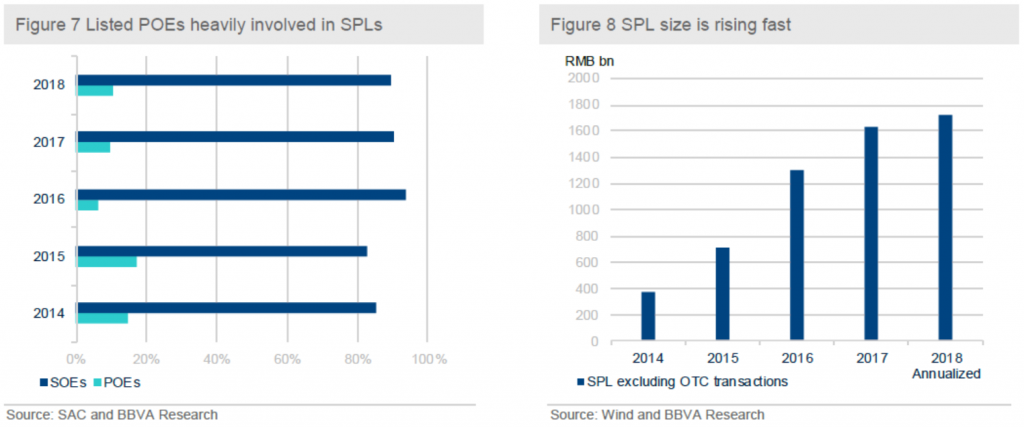

Moreover, huge risks are exposed in a new form of bank business called stock-pledged lending (SPL).In order to obtain funding from banks, some major shareholders of listed POEs used their holding shares as collaterals. SPL businesses grew very fast in the past several years as its total size increased from RMB 337billion in 2014 to RMB 1.6 trillion in 2017 (Figure 7 & 8). Recently sluggish stock market has made the value of collaterals drop below the value of related loans and therefore triggered marginal calls for the borrowers. As such, these listed POEs are under greater financial pressures now.

POEs’ disadvantages relative to SOEs through the deleverage campaign could also be found with listed firms. Based on the information contained in their financial statements, we have constructed two indicators to measure their indebtedness. (Figure 5) One is the ratio of Debt-to-EBITDA, which is a proxy of a firm’s debt level relative to its cash flow. The other is the ratio of EBITDA-to-Interest Expense, which gauges a firm’s capacity to service its interest-bearing debt. A natural threshold of this ratio is 1. A firm with its ratio of EBITDA-to-Interest Expense below this benchmark could have difficulty in servicing its debt. The median of Debt-to-EBITDA ratio among all listed non-SOEs rose in 2017 and the first half of 2018, suggesting that the non-SOEs failed to improve their balance sheets during the deleveraging campaign. The capacity of debt serving for listed non-SOEs also deteriorated in the first half of 2018 as the share of listed non-SOEs with an EBITDA-to-Interest Expense ratio below 1 increased from its level of 2017.

One prime reason why POEs failed to reduce their leverage is the clampdown of shadow banking activities whichhave cut them off funding channels and exposed them to great refinancing risk. At the same time, the formal banking sector was reluctant to increase their support for private enterprises due to both ever-increasing regulatory pressure and worsening economic outlook. As such, China’s deleveraging efforts have mainly squeezed smaller borrowers rather than well capitalized SOEs. Yearly growth of bank lending to small-medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), the majority of which are POEs, moderated to 12.2% in June 2018 from 17.2% a year ago. (Figure 6) Accordingly, the share of new bank lending to SMEs declined to 20.9% of total new corporate loans, a five-year low.

Moreover, huge risks are exposed in a new form of bank business called stock-pledged lending (SPL).In order to obtain funding from banks, some major shareholders of listed POEs used their holding shares as collaterals. SPL businesses grew very fast in the past several years as its total size increased from RMB 337billion in 2014 to RMB 1.6 trillion in 2017 (Figure 7 & 8). Recently sluggish stock market has made the value of collaterals drop below the value of related loans and therefore triggered marginal calls for the borrowers. As such, these listed POEs are under greater financial pressures now. The authorities have shifted their policy stance to pro-growth…

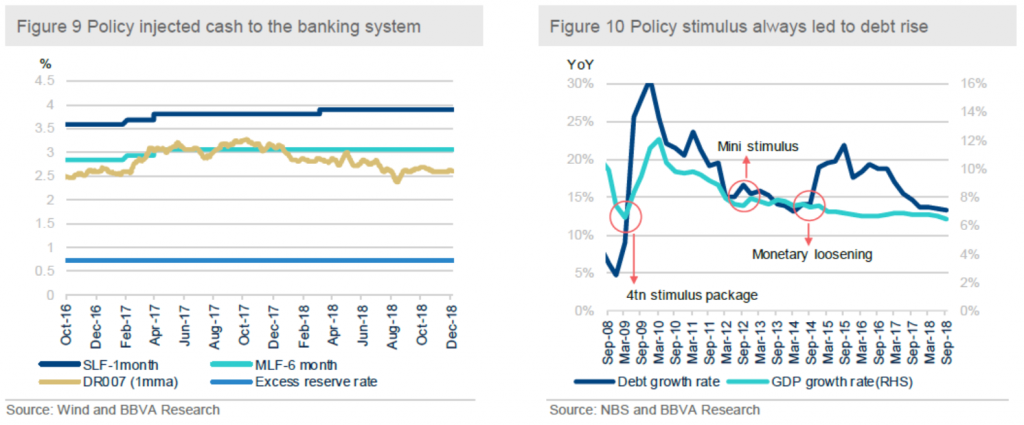

In face of intensifying growth headwinds and POE woes, the authorities changed their policy tones from “deleveraging” to “stabilizing firms’ leverage”. In particular, the central bank cut the bank reserve requirement ratio by 1% effective Oct. 15 and expanding the range of pledged assets for commercial banks to apply for Mid-term Lending Facilities (MLF). The move will inject a net 750 billion yuan (USD 10.9.2billion) in cash into the banking system by releasing a total of 1.2 trillion yuan in liquidity. (Figure 9) The authorities also implemented a series of policy initiatives to support Small and Medium Enterprises(SMEs),including highlighting the big banks’ efforts to boost lending to cash-starved small firms, offering collateral waivers and setting loan targets to SMEs. To guide lending to small firms, authorities have issued directives to banks, arranged meetings between executives of banks and private firms, and doled out tax breaks for banks’ “micro-loans”,etc.

On the fiscal front, the authorities have implemented a series of tax cuts in various perspectives to reduce the costs and stimulate growth since this year. The authorities have cut the payroll tax for individuals and enterprises, including the adjustment of personal income tax, VAT and import tax etc. These measures will cut the enterprises’ cost and thus help with the deleveraging process. The VAT cuts are expected to save 240 billion yuan (USD 38 billion) in taxes this year, thus will boost the real economy through reducing corporate burdens and create a stable and fair business environment.

…which could lead to the rise of leverage again

According to the past experience, policy stimulus was always followed by the rise of the country’s debt level (Figure 10).If not handled carefully, the corporate debt issue will become acute again in the next few years. That being said, China authorities should strike a balance between sustaining a decent growth rate and limiting the pace of debt increase. We believe that the following suggestions could help the authorities to achieve the balanced objectives.

The authorities have shifted their policy stance to pro-growth…

In face of intensifying growth headwinds and POE woes, the authorities changed their policy tones from “deleveraging” to “stabilizing firms’ leverage”. In particular, the central bank cut the bank reserve requirement ratio by 1% effective Oct. 15 and expanding the range of pledged assets for commercial banks to apply for Mid-term Lending Facilities (MLF). The move will inject a net 750 billion yuan (USD 10.9.2billion) in cash into the banking system by releasing a total of 1.2 trillion yuan in liquidity. (Figure 9) The authorities also implemented a series of policy initiatives to support Small and Medium Enterprises(SMEs),including highlighting the big banks’ efforts to boost lending to cash-starved small firms, offering collateral waivers and setting loan targets to SMEs. To guide lending to small firms, authorities have issued directives to banks, arranged meetings between executives of banks and private firms, and doled out tax breaks for banks’ “micro-loans”,etc.

On the fiscal front, the authorities have implemented a series of tax cuts in various perspectives to reduce the costs and stimulate growth since this year. The authorities have cut the payroll tax for individuals and enterprises, including the adjustment of personal income tax, VAT and import tax etc. These measures will cut the enterprises’ cost and thus help with the deleveraging process. The VAT cuts are expected to save 240 billion yuan (USD 38 billion) in taxes this year, thus will boost the real economy through reducing corporate burdens and create a stable and fair business environment.

…which could lead to the rise of leverage again

According to the past experience, policy stimulus was always followed by the rise of the country’s debt level (Figure 10).If not handled carefully, the corporate debt issue will become acute again in the next few years. That being said, China authorities should strike a balance between sustaining a decent growth rate and limiting the pace of debt increase. We believe that the following suggestions could help the authorities to achieve the balanced objectives. First, the authorities should commit to the clampdown of shadow banking activities and encourage formal banking sector to extend more credit to SMEs. Shadow banking activities have been the prime culprit for China’s credit binge in the past. If the authorities want to keep debt growth at a sustainable pace, they should not relax their existing regulations for shadow banking activities.

Second, the authorities should make fiscal policy spearhead the stimulus package this time. In particular, the authorities could be more aggressive in cutting taxes for the corporate sector and providing support for SMEs rather than resorting to monetary loosening. The key difference is that additional fiscal initiatives are likely to improve corporate balance sheets and increase the debt level of China’s central government which still looks healthy (47% of GDP in 2017).

Last but not least, the authorities should seek to solve the trade tensions with the US as soon as possible. Export is the type of economic activities which generates growth with less credit consumption. If the authorities want to see a credit-less growth, they must find the ways to reactivate the powerful exporting machine.

All in all, stimulating growth and controlling debt at the same time is a very challenging task for China’s authorities. They still have the chance to make this time different if appropriate policy initiatives are to be implemented.

First, the authorities should commit to the clampdown of shadow banking activities and encourage formal banking sector to extend more credit to SMEs. Shadow banking activities have been the prime culprit for China’s credit binge in the past. If the authorities want to keep debt growth at a sustainable pace, they should not relax their existing regulations for shadow banking activities.

Second, the authorities should make fiscal policy spearhead the stimulus package this time. In particular, the authorities could be more aggressive in cutting taxes for the corporate sector and providing support for SMEs rather than resorting to monetary loosening. The key difference is that additional fiscal initiatives are likely to improve corporate balance sheets and increase the debt level of China’s central government which still looks healthy (47% of GDP in 2017).

Last but not least, the authorities should seek to solve the trade tensions with the US as soon as possible. Export is the type of economic activities which generates growth with less credit consumption. If the authorities want to see a credit-less growth, they must find the ways to reactivate the powerful exporting machine.

All in all, stimulating growth and controlling debt at the same time is a very challenging task for China’s authorities. They still have the chance to make this time different if appropriate policy initiatives are to be implemented.