Steve H. Hanke: Monetary Policies Misunderstood

2016-05-06 IMI The Eurozone arrived at the QE party a bit late. But, it arrived nevertheless. Now, European Central Bank (ECB) President Mario Draghi and QE face a wave of criticism. Many in Germany, for example, oppose QE. Many even argue that the ECB (and other central banks) are out of ammunition. This is nonsense.

Let’s take a look at one QE operation that would directly boost the money supply without increasing the government’s net debt. The process begins with the government borrowing from commercial banks. Short-dated government paper is transferred to banks. In exchange, the deposit balance of the government is credited.

This new government deposit is not counted as a part of the money supply. The government then uses its bank deposits (which are not considered money) to purchase long-dated government bonds from the non-bank private sector. These transactions add to the non-bank private sector’s bank deposits and directly to the money supply, because bank deposits in the name of private persons and entities are money. So, the quantity of money is directly increased by this debt market operation, and an equivalent amount of long-dated government debt is reduced — literally eliminated.

Of course, the amount of short-dated government debt increases when the government initially borrows from the commercial banks. Accordingly, these debt market operations leave the government’s total net debt unchanged, but it does change the composition of the government’s debt, leaving it with a shorter average duration.

So, forget claims that central banks are out of ammunition. Again, the reason that most come to that incorrect conclusion is that they focus on interest rates.

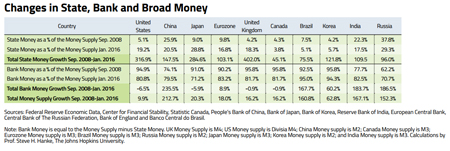

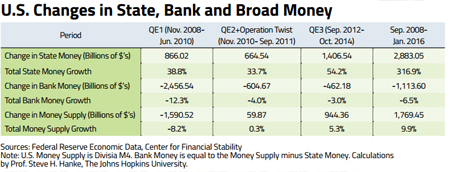

Moving from the broad picture to the U.S., we see in the accompanying table that there have been three QEs. Their impact on state, bank, and broad money is shown in the table. Each QE was associated with a significant increase in state money, which offset, to some degree, the negative “contributions” of bank money to the total supply of broad money.

The Eurozone arrived at the QE party a bit late. But, it arrived nevertheless. Now, European Central Bank (ECB) President Mario Draghi and QE face a wave of criticism. Many in Germany, for example, oppose QE. Many even argue that the ECB (and other central banks) are out of ammunition. This is nonsense.

Let’s take a look at one QE operation that would directly boost the money supply without increasing the government’s net debt. The process begins with the government borrowing from commercial banks. Short-dated government paper is transferred to banks. In exchange, the deposit balance of the government is credited.

This new government deposit is not counted as a part of the money supply. The government then uses its bank deposits (which are not considered money) to purchase long-dated government bonds from the non-bank private sector. These transactions add to the non-bank private sector’s bank deposits and directly to the money supply, because bank deposits in the name of private persons and entities are money. So, the quantity of money is directly increased by this debt market operation, and an equivalent amount of long-dated government debt is reduced — literally eliminated.

Of course, the amount of short-dated government debt increases when the government initially borrows from the commercial banks. Accordingly, these debt market operations leave the government’s total net debt unchanged, but it does change the composition of the government’s debt, leaving it with a shorter average duration.

So, forget claims that central banks are out of ammunition. Again, the reason that most come to that incorrect conclusion is that they focus on interest rates.

Moving from the broad picture to the U.S., we see in the accompanying table that there have been three QEs. Their impact on state, bank, and broad money is shown in the table. Each QE was associated with a significant increase in state money, which offset, to some degree, the negative “contributions” of bank money to the total supply of broad money.

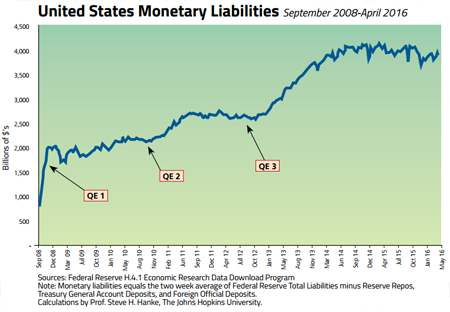

The accompanying chart traces out the monetary liabilities of the Fed and profiles the course of state money since the Lehman Brothers bankruptcy. By the summer of 2014, QE 3 had run its course, and the level of state money has remained stable.

The accompanying chart traces out the monetary liabilities of the Fed and profiles the course of state money since the Lehman Brothers bankruptcy. By the summer of 2014, QE 3 had run its course, and the level of state money has remained stable.

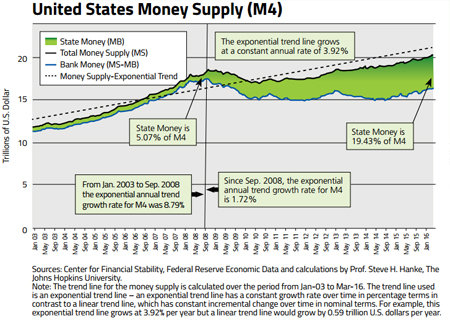

The last chart depicts the huge expansion of state money. That’s shown by the widening of the green area since the Lehman Brothers collapse. Although expansive, the QE has hardly been enough to offset the tightness in bank money. In consequence, broad money has only been growing at a 1.72 percent annual growth rate since October 2008. So, it’s not surprising that nominal GDP has grown relatively slowly and that we have not witnessed the inflation surge predicted by many who were only watching the Fed’s balance sheet balloon.

The last chart depicts the huge expansion of state money. That’s shown by the widening of the green area since the Lehman Brothers collapse. Although expansive, the QE has hardly been enough to offset the tightness in bank money. In consequence, broad money has only been growing at a 1.72 percent annual growth rate since October 2008. So, it’s not surprising that nominal GDP has grown relatively slowly and that we have not witnessed the inflation surge predicted by many who were only watching the Fed’s balance sheet balloon.

To say that money and monetary policies are misunderstood is an understatement. What’s worrying is that the political class does not have the faintest understanding of the importance of bank money. Their populist bank-bashing rhetoric and regulations are putting a drag on the growth of bank money and economic activity.

To say that money and monetary policies are misunderstood is an understatement. What’s worrying is that the political class does not have the faintest understanding of the importance of bank money. Their populist bank-bashing rhetoric and regulations are putting a drag on the growth of bank money and economic activity.