Dong Jinyue, Alvaro Ortiz and Xia Le: From Great Miracle to Great Moderation—Potential GDP Estimation of China

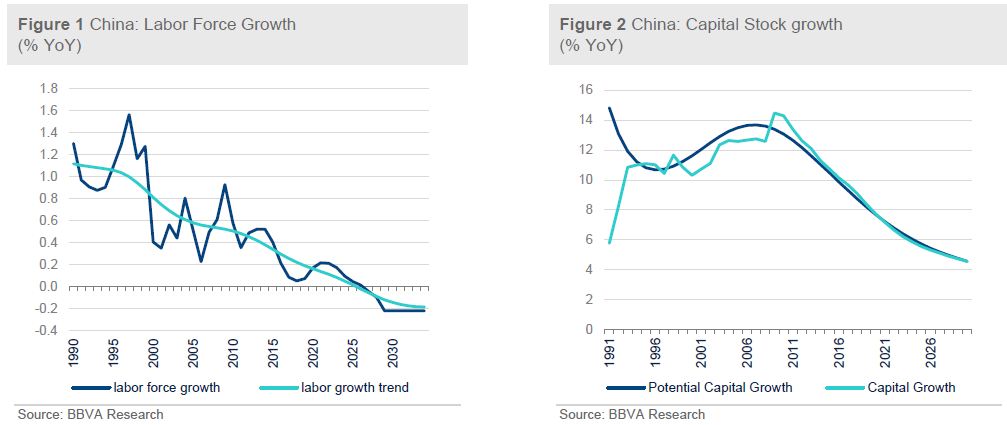

2018-01-15 IMI 2.The aging population will unavoidably slow labor contribution over the medium-long term. The labor supply will continue to moderate (at an average rate at -0.2% between 2030 and 2035). This is mainly the result of population dynamics as structural unemployment rate will remain at similar level and moderate increases in the participation rate will not prevent the negative effect of the declining labor force. (Figure 2)

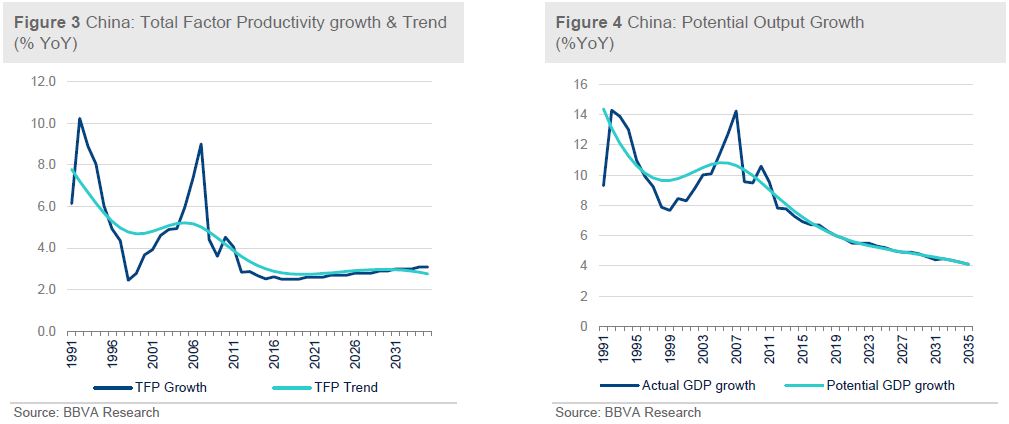

3.We expect that the technological progress or TFP growth will become the main driver of China’s growth in the long term (replacing capital accumulation as the main driver). We maintain a balanced assumption of TFP growth to maintain similar growth rate as the last two decades in the long-term trend2 (in the range of 2.5%-3.0%). (Figure 3)

2.The aging population will unavoidably slow labor contribution over the medium-long term. The labor supply will continue to moderate (at an average rate at -0.2% between 2030 and 2035). This is mainly the result of population dynamics as structural unemployment rate will remain at similar level and moderate increases in the participation rate will not prevent the negative effect of the declining labor force. (Figure 2)

3.We expect that the technological progress or TFP growth will become the main driver of China’s growth in the long term (replacing capital accumulation as the main driver). We maintain a balanced assumption of TFP growth to maintain similar growth rate as the last two decades in the long-term trend2 (in the range of 2.5%-3.0%). (Figure 3)

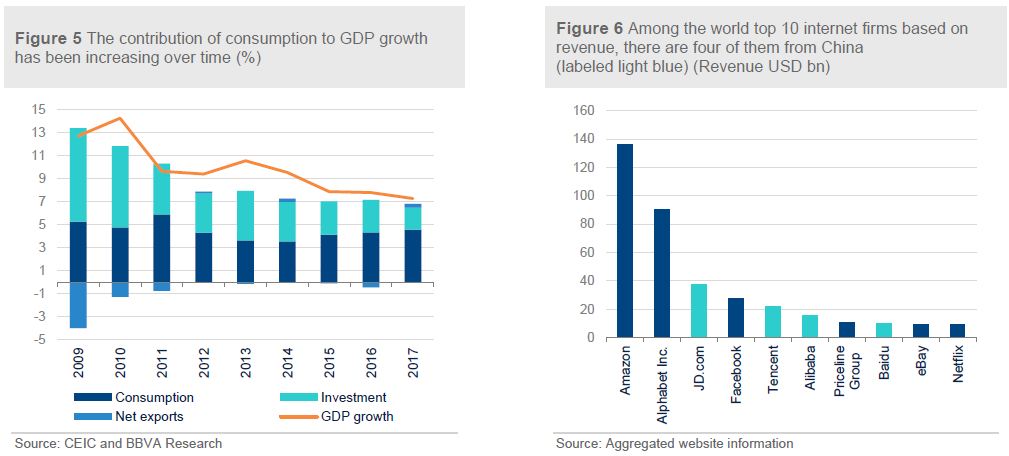

Based on our assumptions above, the potential GDP growth will gradually moderate from the current level of 6.5% to near 5% in 2025 and then to 4% in 2035 (Figure 4). The sources of growth will change and the contribution of total factor productivity to GDP growth will overtake that of the capital growth as growth become increasingly dependent on technology innovation and investment continues to adjust (Figure 5). According to our estimation, China’s authorities’ long-term target of “socialist modernization” is quite attainable despite the gradual slowdown in potential GDP. In particular, China’s per capita GDP stood at USD 8,123 in 2016, the trend of our estimated potential GDP will bring this figure to around USD 21,000 (constant price of today) by 2035.

How our estimations of potential GDP in China will compare to the US? Assuming an average 2.5% growth rate for the US till 2035, the “great shift” in global economic power is not going to happen by 2035 but the two economic giants will be at similar level. However, the GDP per capita in China will only accounts for 26% of that in the US.

Chinese version of “Great Moderation”

If China’s growth track can follow its potential GDP we estimated above, it means that the economy will enter a period of Great Moderation over the next two decades as observed in the US and other advanced countries during the 20 years in the run-up of the 2008-2009 Global Financial Crisis. Just like its precedent in advanced countries, this Chinese version of Great Moderation features in: (i) marked reduction in the volatility of business cycle fluctuations, especially the output and inflation; (ii) a protracted period of a slower but sustainable economic growth with economic rebalancing in contrast to the current credit-fuelled growth; and (iii) a lower degree of intervention in the economy.

Although the exact reasons behind the Great Moderation in advanced countries still remain a debatable question, we do find that today’s China bears some resemblance to the US during its period of Great Moderation:

First, both Great Moderation periods happen after a long period of economic slowdown. From 1970 to mid-1980s, right after the collapse of Bretton Woods system, the US economy experienced more than ten years of economic slowdown, featuring by hyperinflation (1970-1975) and the sequential deflation and high deficit. Similarly, Chinese economy has moderated from its fast growth period after the Global Financial Crisis and is now undergoing certain structural changes as for example the increase in the more stable service sector in the economy.

Second, both China and the US enjoyed the benefits of human capital accumulation due to the “baby boom”. The baby boom in the US in 1940s and 1950s, after the Second World War, brought a large amount of working population in mid-1980s to pre-Global Financial Crisis. The baby boom in China occurred in 1970s and 1980s after China implemented reform and opening-up policy. Now China is enjoying the demographic dividend from its baby boomers although its aging process is supposed to be fast than the US due to the birth control policy.

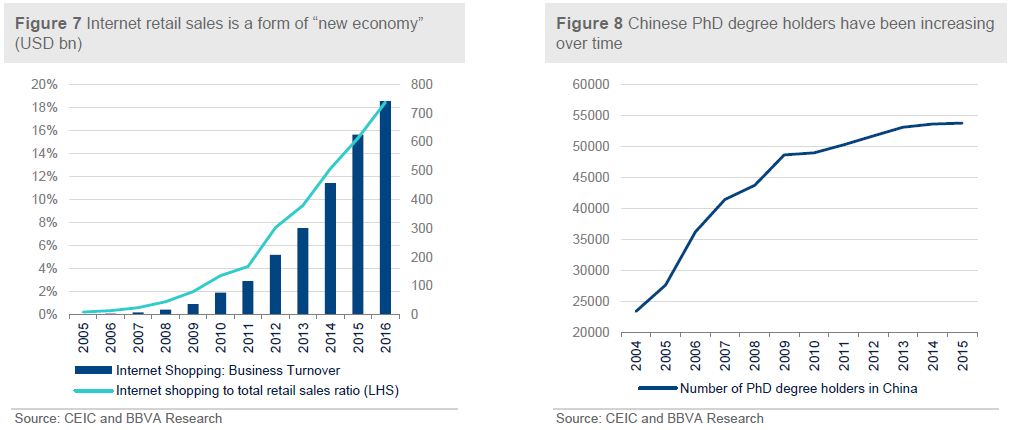

Third, the US Great Moderation came together with the launch of new economy. One stream of the explanations for the US Great Moderation is regarding on the structural change, which suggests that changes in economic institutions, technology, business practices, or other structural features of the economy as the increase of the service sector have improved the ability of the economy to absorb shocks. In particular, it is labeled by widely usage and adaptation of the Internet by businesses and consumers in 1980s. For China, the recent development of FinTech, information technology, E-commerce and new energy also indicates the arrival of the “new economy”. As mentioned, we don’t envisage a rapid acceleration of productivity coming from the tech revolution but rather maintenance of the recent trend. (Figure 6-8).

Based on our assumptions above, the potential GDP growth will gradually moderate from the current level of 6.5% to near 5% in 2025 and then to 4% in 2035 (Figure 4). The sources of growth will change and the contribution of total factor productivity to GDP growth will overtake that of the capital growth as growth become increasingly dependent on technology innovation and investment continues to adjust (Figure 5). According to our estimation, China’s authorities’ long-term target of “socialist modernization” is quite attainable despite the gradual slowdown in potential GDP. In particular, China’s per capita GDP stood at USD 8,123 in 2016, the trend of our estimated potential GDP will bring this figure to around USD 21,000 (constant price of today) by 2035.

How our estimations of potential GDP in China will compare to the US? Assuming an average 2.5% growth rate for the US till 2035, the “great shift” in global economic power is not going to happen by 2035 but the two economic giants will be at similar level. However, the GDP per capita in China will only accounts for 26% of that in the US.

Chinese version of “Great Moderation”

If China’s growth track can follow its potential GDP we estimated above, it means that the economy will enter a period of Great Moderation over the next two decades as observed in the US and other advanced countries during the 20 years in the run-up of the 2008-2009 Global Financial Crisis. Just like its precedent in advanced countries, this Chinese version of Great Moderation features in: (i) marked reduction in the volatility of business cycle fluctuations, especially the output and inflation; (ii) a protracted period of a slower but sustainable economic growth with economic rebalancing in contrast to the current credit-fuelled growth; and (iii) a lower degree of intervention in the economy.

Although the exact reasons behind the Great Moderation in advanced countries still remain a debatable question, we do find that today’s China bears some resemblance to the US during its period of Great Moderation:

First, both Great Moderation periods happen after a long period of economic slowdown. From 1970 to mid-1980s, right after the collapse of Bretton Woods system, the US economy experienced more than ten years of economic slowdown, featuring by hyperinflation (1970-1975) and the sequential deflation and high deficit. Similarly, Chinese economy has moderated from its fast growth period after the Global Financial Crisis and is now undergoing certain structural changes as for example the increase in the more stable service sector in the economy.

Second, both China and the US enjoyed the benefits of human capital accumulation due to the “baby boom”. The baby boom in the US in 1940s and 1950s, after the Second World War, brought a large amount of working population in mid-1980s to pre-Global Financial Crisis. The baby boom in China occurred in 1970s and 1980s after China implemented reform and opening-up policy. Now China is enjoying the demographic dividend from its baby boomers although its aging process is supposed to be fast than the US due to the birth control policy.

Third, the US Great Moderation came together with the launch of new economy. One stream of the explanations for the US Great Moderation is regarding on the structural change, which suggests that changes in economic institutions, technology, business practices, or other structural features of the economy as the increase of the service sector have improved the ability of the economy to absorb shocks. In particular, it is labeled by widely usage and adaptation of the Internet by businesses and consumers in 1980s. For China, the recent development of FinTech, information technology, E-commerce and new energy also indicates the arrival of the “new economy”. As mentioned, we don’t envisage a rapid acceleration of productivity coming from the tech revolution but rather maintenance of the recent trend. (Figure 6-8).

Still some challenges ahead…

Although we have observed some good signs of economic and institutional improvement recently, we still have a long way to arrive at the Great Moderation period. Risks of the economy from various perspectives still exist, and they are significantly inter-connected at economic, political and social levels. Thus, the balance between maintaining a decent growth rate and pushing forward the structural reforms still remains as the biggest challenge for the authorities at the current stage.

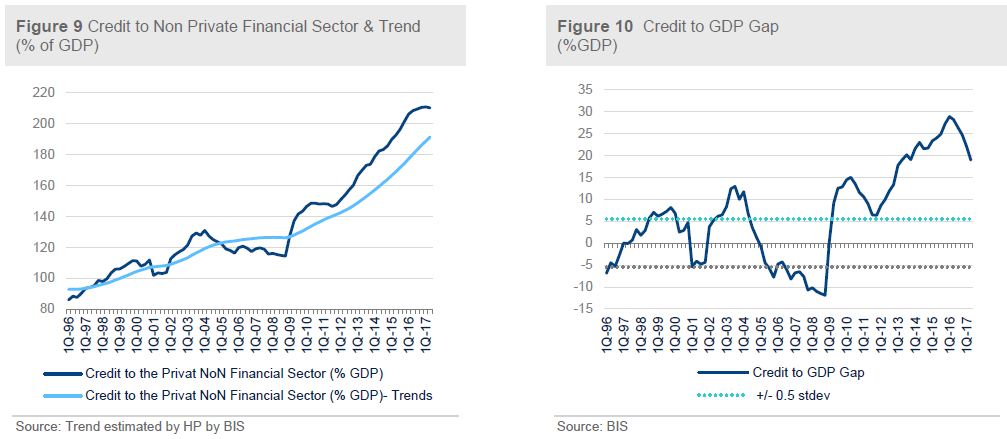

First, China needs to completely change the credit-fuelled and investment-led growth model and solve the debt problem. China´s credit to non-financial private sector accelerated significantly since the aftermath of 2008-2009 Global Financial Crisis, thanks to a series of stimulus packages enacted by the authorities to counter external shocks, which led China to grow an addiction to the credit-fuelled growth. According to the BIS figures, China´s credit to non-financial private sector ration increased near 100 pp (Figure 9) triggering a rapid increase of the Credit Gap (Figure 10). Fortunately, Chinese authorities started to react after the mini-crisis at the beginning of 2016. Since then, the Credit to GDP ratio has stabilized and the credit gap has already decreased by 10 pp according to the BIS figures. Achieving the Great Moderation will be highly conditioned on this situation to continue in order to avoid a sharp correction of credit, investment, capital, unemployment and, furthermore, a significantly lower potential GDP.

Still some challenges ahead…

Although we have observed some good signs of economic and institutional improvement recently, we still have a long way to arrive at the Great Moderation period. Risks of the economy from various perspectives still exist, and they are significantly inter-connected at economic, political and social levels. Thus, the balance between maintaining a decent growth rate and pushing forward the structural reforms still remains as the biggest challenge for the authorities at the current stage.

First, China needs to completely change the credit-fuelled and investment-led growth model and solve the debt problem. China´s credit to non-financial private sector accelerated significantly since the aftermath of 2008-2009 Global Financial Crisis, thanks to a series of stimulus packages enacted by the authorities to counter external shocks, which led China to grow an addiction to the credit-fuelled growth. According to the BIS figures, China´s credit to non-financial private sector ration increased near 100 pp (Figure 9) triggering a rapid increase of the Credit Gap (Figure 10). Fortunately, Chinese authorities started to react after the mini-crisis at the beginning of 2016. Since then, the Credit to GDP ratio has stabilized and the credit gap has already decreased by 10 pp according to the BIS figures. Achieving the Great Moderation will be highly conditioned on this situation to continue in order to avoid a sharp correction of credit, investment, capital, unemployment and, furthermore, a significantly lower potential GDP.

Fortunately, at the concluded 19th Party Congress the authorities have abandoned the previous ambitious target of doubling the size of the economy between 2010 and 2020 which constrained the ability of economic policymakers to put the economy in a sustainable path. Still, the authorities need to enhance efforts to address the existing huge stock of debt. Importantly, the last year’s growth model – relying on increasing government spending to fund infrastructure programs and allowing state-owned banks to lend more for speculative property developments - should be radically changed. The new strategy should address these old vicious urgently through a comprehensive strategy, including proactively recognizing losses in the financial system, corporate restructuring and corporate governance reform, hardening budget constraints, etc.

Second, which is related to the previous one, the authorities should avoid systematic financial risks and continue the on-going financial deleveraging. The surge in shadow banking is impairing China’s debt problem and posing additional risks to the financial sector, as the credit boom has been driven in part by shadow banking finance products used to funnel credit to local governments and businesses that have difficulties in getting regular bank loans. At the current stage, the financial intermediate chain, which indicates the time taken from the capital providers to the ultimate users, has been lengthening over time, suggesting an increasingly sophisticated structure of shadow banking activities. Thus, as these off-balance sheet activities are not subject to banking regulations, any collapse from the final investment destination of shadow banking, such as housing, non-standard credit assets (NSCA), bond, derivatives and money market instruments etc., will lead to systematic risks for the financial sector.

Last, the SOE reform (together with the on-going supply-side reform) needs to be continuously pushed forward beyond the already positive signs of SOE reform. Here, there is still a long way to go given the SOEs’ huge presence and the regulatory bureaucracy. Since 2015, the main focus of SOE reform has been on promoting mixed ownership between the government and private sector, which has improved corporate governance in some cases. But it should be noted that SOEs are to some extent administrative arms of the government and interests are not entirely separate. In fact, the objective of the mixed ownership reform is not to reduce effective government control but to increase private funding for SOEs. Beyond Governance, some of the overcapacity problems of SOEs will be eased with the increasing importance of the One Belt One Road (OBOR) strategy.

But room for the upside too if technological progress accelerates…

Our assumption for Technology Progress (approximated by TFP growth) is modest as we envisage a 3.0% productivity growth while productivity averaged near 5% according to Klems estimations during the last three decades. True, China will enter the Great Moderation period and this also includes productivity growth pick-up as China will rise in the ladder of development leaving behind the high growth transition period. A number of factors could justify our assumption that the TFP growth or result in even higher productivity growth rate.

First, the productivity in China still lags behind that of the advanced countries. For example, China’s per capita GDP only accounts for 15.8% of that of the US. That being said, it has a great potential for China to continuously improve its productivity over the long run. Second, a number of new industries have shown excellent growth momentum in China, including the FinTech, IT, E-commerce, High-speed Railway and new energy etc. The lack of “legacies” in Chinese digital revolution could spur a higher-than-expected impact on technology adoption than in the Western countries thus widening the effects of technology on the economy. Last but not least, the current level of the TFP has been to certain extent repressed by the authorities’ prevalent support for low-productive SOEs. We anticipate the ongoing SOE reforms to eliminate inefficient firms and correct the misallocation of capital and labour in the economy, which will help to boost the general level of TFP.

Thus productivity “is not all but it can be almost all” in Chinese future potential. If China manages to increase productivity growth beyond “normal”, it could add an extra 1%-1.5% pp to potential output in the coming years.

Fortunately, at the concluded 19th Party Congress the authorities have abandoned the previous ambitious target of doubling the size of the economy between 2010 and 2020 which constrained the ability of economic policymakers to put the economy in a sustainable path. Still, the authorities need to enhance efforts to address the existing huge stock of debt. Importantly, the last year’s growth model – relying on increasing government spending to fund infrastructure programs and allowing state-owned banks to lend more for speculative property developments - should be radically changed. The new strategy should address these old vicious urgently through a comprehensive strategy, including proactively recognizing losses in the financial system, corporate restructuring and corporate governance reform, hardening budget constraints, etc.

Second, which is related to the previous one, the authorities should avoid systematic financial risks and continue the on-going financial deleveraging. The surge in shadow banking is impairing China’s debt problem and posing additional risks to the financial sector, as the credit boom has been driven in part by shadow banking finance products used to funnel credit to local governments and businesses that have difficulties in getting regular bank loans. At the current stage, the financial intermediate chain, which indicates the time taken from the capital providers to the ultimate users, has been lengthening over time, suggesting an increasingly sophisticated structure of shadow banking activities. Thus, as these off-balance sheet activities are not subject to banking regulations, any collapse from the final investment destination of shadow banking, such as housing, non-standard credit assets (NSCA), bond, derivatives and money market instruments etc., will lead to systematic risks for the financial sector.

Last, the SOE reform (together with the on-going supply-side reform) needs to be continuously pushed forward beyond the already positive signs of SOE reform. Here, there is still a long way to go given the SOEs’ huge presence and the regulatory bureaucracy. Since 2015, the main focus of SOE reform has been on promoting mixed ownership between the government and private sector, which has improved corporate governance in some cases. But it should be noted that SOEs are to some extent administrative arms of the government and interests are not entirely separate. In fact, the objective of the mixed ownership reform is not to reduce effective government control but to increase private funding for SOEs. Beyond Governance, some of the overcapacity problems of SOEs will be eased with the increasing importance of the One Belt One Road (OBOR) strategy.

But room for the upside too if technological progress accelerates…

Our assumption for Technology Progress (approximated by TFP growth) is modest as we envisage a 3.0% productivity growth while productivity averaged near 5% according to Klems estimations during the last three decades. True, China will enter the Great Moderation period and this also includes productivity growth pick-up as China will rise in the ladder of development leaving behind the high growth transition period. A number of factors could justify our assumption that the TFP growth or result in even higher productivity growth rate.

First, the productivity in China still lags behind that of the advanced countries. For example, China’s per capita GDP only accounts for 15.8% of that of the US. That being said, it has a great potential for China to continuously improve its productivity over the long run. Second, a number of new industries have shown excellent growth momentum in China, including the FinTech, IT, E-commerce, High-speed Railway and new energy etc. The lack of “legacies” in Chinese digital revolution could spur a higher-than-expected impact on technology adoption than in the Western countries thus widening the effects of technology on the economy. Last but not least, the current level of the TFP has been to certain extent repressed by the authorities’ prevalent support for low-productive SOEs. We anticipate the ongoing SOE reforms to eliminate inefficient firms and correct the misallocation of capital and labour in the economy, which will help to boost the general level of TFP.

Thus productivity “is not all but it can be almost all” in Chinese future potential. If China manages to increase productivity growth beyond “normal”, it could add an extra 1%-1.5% pp to potential output in the coming years.