Herbert Poenisch: From Domestic to Global Banking-A Survey of Banking Systems in 31 Countries

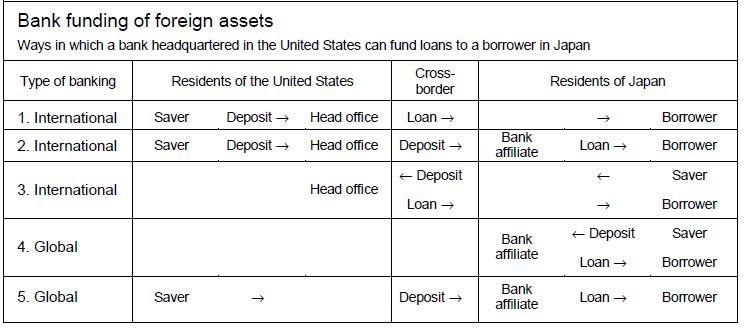

2018-01-02 IMI Source: McCauley et al, BIS 2003

1.4 Internationalisation of banking

Once these branches and subsidiaries were set up or local banks acquired through M&A in the 1990s not only infinancialcentres but in other prosperous emerging markets, they started lending to domestic clients in the host countries. The bulk of funding came still from the mother bank during this period (see scheme above). Thus this type of banking was reflected in the BOP as a capital outflows, partially compensated on the current account by interest earnings and dividends received.

The main drivers of the internationalization in this period were the push-pull factors[x]. On the push side, the overbanking in many advanced countries which led to banking consolidation with fewer more powerful players ready to expand overseas , were facing small lending margins and falling profitability. On the pull side, emerging markets borrowers became eligible to borrow from the foreign banks, because domestic growth and structural reforms allowed domestic borrowers to service their bank loans. In addition, emerging markets became more transparent which helped the risk assessment by foreign banks.

This was tested during the various financial crises in emerging markets, notably the Mexican Crisis of the mid 1990s and theAsian Crisis of the late 1990s. In the aftermath of these crises, authorities in emerging market economies sought to recapitalize their ailing banking systems and improve the overall efficiency of their financial sectors with the help of foreign banks[xi].During this period many large customers in prosperous emerging markets shifted from bank borrowing to capital markets, share issues and domestic bond borrowing[xii]. Although economic growth was good, bank lending did not reflect the full dynamics.

1.5 Globalisation of international banking

By the beginning of the new century, prosperous emerging markets became more sophisticated in choosing and regulating foreign banks to provide a level playing field with their own banking champions.The presence of foreign banks has generally led domestic supervisory authorities to upgrade thequality and increase the size of their staff in order to supervise the more sophisticated activities andnew products being introduced by these banks[xiii].At the same time regulatory pressure on the mother banks became an incentive to deal with branches and subsidiaries at arms’ length.

International banks became global players when they took responsibility for their own destiny, funding as well as risk management. They behaved like local banks, even running a branch network and accepting deposits from domestic customers[xiv].

While this business continued to flourish, there was no reflection in the BOP because no capital flowed from the mother bank to finance the operations of branches and subsidiaries. They engage in local borrowing and lending, not classified as international transaction in the BOP accounting framework. As a result, standard BOPbasedmeasures of financial openness tend to underestimate the degree of globalbanking interconnectedness[xv].

Although this type of business largely escapes the BOP, the BIS banking statistics in the consolidated banking statistics (CBS) take this into account by recording the local business in host countries by internationally active banks[xvi].

What happened was fundsrather flowing the other way, once the mother banks ran into problems. The Japanese banks recalled funds already in the 1990s leading to negative capital outflows in Japan; the European banks’ retrenchment followed after the Global Financial Crisis[xvii] and continues until today. Overseas US banks stabilized their operation without major retrenchment. What has happened was rather a restructuring than a retreat from globalization in the following sense.

The local or regional operations sold off by international banks were bought by local banks ambitious to internationalise their operations. They in turn became regional important players, such as Singaporean and Malaysian banks in ASEAN and Brazilian and Mexican banks in Latin America. Chinese banks have adopted a similar strategy. Matching their global peers, their funding was originally from the mother bank but is becoming increasing local. When this is achieved there will be less reflection in the financial account of the BOP. Global banking has thus a greater variety of players with more local focus[xviii].

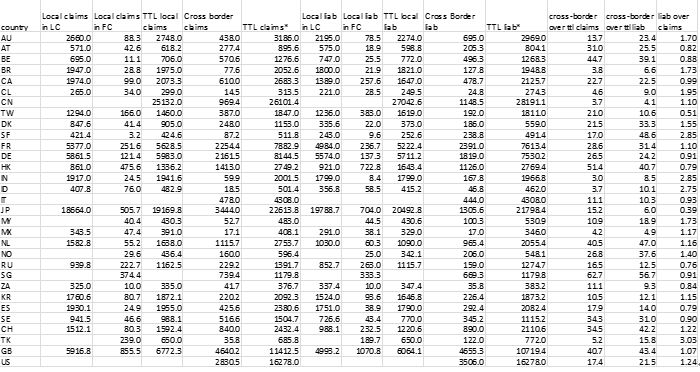

Table: Domestic and cross-border banking claims and liabilities in 31 sample countries

Source: McCauley et al, BIS 2003

1.4 Internationalisation of banking

Once these branches and subsidiaries were set up or local banks acquired through M&A in the 1990s not only infinancialcentres but in other prosperous emerging markets, they started lending to domestic clients in the host countries. The bulk of funding came still from the mother bank during this period (see scheme above). Thus this type of banking was reflected in the BOP as a capital outflows, partially compensated on the current account by interest earnings and dividends received.

The main drivers of the internationalization in this period were the push-pull factors[x]. On the push side, the overbanking in many advanced countries which led to banking consolidation with fewer more powerful players ready to expand overseas , were facing small lending margins and falling profitability. On the pull side, emerging markets borrowers became eligible to borrow from the foreign banks, because domestic growth and structural reforms allowed domestic borrowers to service their bank loans. In addition, emerging markets became more transparent which helped the risk assessment by foreign banks.

This was tested during the various financial crises in emerging markets, notably the Mexican Crisis of the mid 1990s and theAsian Crisis of the late 1990s. In the aftermath of these crises, authorities in emerging market economies sought to recapitalize their ailing banking systems and improve the overall efficiency of their financial sectors with the help of foreign banks[xi].During this period many large customers in prosperous emerging markets shifted from bank borrowing to capital markets, share issues and domestic bond borrowing[xii]. Although economic growth was good, bank lending did not reflect the full dynamics.

1.5 Globalisation of international banking

By the beginning of the new century, prosperous emerging markets became more sophisticated in choosing and regulating foreign banks to provide a level playing field with their own banking champions.The presence of foreign banks has generally led domestic supervisory authorities to upgrade thequality and increase the size of their staff in order to supervise the more sophisticated activities andnew products being introduced by these banks[xiii].At the same time regulatory pressure on the mother banks became an incentive to deal with branches and subsidiaries at arms’ length.

International banks became global players when they took responsibility for their own destiny, funding as well as risk management. They behaved like local banks, even running a branch network and accepting deposits from domestic customers[xiv].

While this business continued to flourish, there was no reflection in the BOP because no capital flowed from the mother bank to finance the operations of branches and subsidiaries. They engage in local borrowing and lending, not classified as international transaction in the BOP accounting framework. As a result, standard BOPbasedmeasures of financial openness tend to underestimate the degree of globalbanking interconnectedness[xv].

Although this type of business largely escapes the BOP, the BIS banking statistics in the consolidated banking statistics (CBS) take this into account by recording the local business in host countries by internationally active banks[xvi].

What happened was fundsrather flowing the other way, once the mother banks ran into problems. The Japanese banks recalled funds already in the 1990s leading to negative capital outflows in Japan; the European banks’ retrenchment followed after the Global Financial Crisis[xvii] and continues until today. Overseas US banks stabilized their operation without major retrenchment. What has happened was rather a restructuring than a retreat from globalization in the following sense.

The local or regional operations sold off by international banks were bought by local banks ambitious to internationalise their operations. They in turn became regional important players, such as Singaporean and Malaysian banks in ASEAN and Brazilian and Mexican banks in Latin America. Chinese banks have adopted a similar strategy. Matching their global peers, their funding was originally from the mother bank but is becoming increasing local. When this is achieved there will be less reflection in the financial account of the BOP. Global banking has thus a greater variety of players with more local focus[xviii].

Table: Domestic and cross-border banking claims and liabilities in 31 sample countries

In bn USD at the end of 2Q2017

Sources: BIS LBS, PBOC, BNM, TCMB, FED *total is not the sum of components due to unallocated items. LC=local currency, FC=foreign currency

Section 2: Observations on the domestic versus cross-border banking statistics

The first observation to be made is the absolute size of the total claims (columns 4 and 6) and liabilities (columns 9 and 11). The size of bank lending is largest in China and Japan, both countries dominated by bank finance rather than capital markets. The US figure is much smaller as capital markets play a more important role.

The second observation is that lending in big countries is usually dominated by domestic lending, with cross-border business playing a small role. Examples are Brazil, China, India, Indonesia and Mexico. Other big countries have individual explanatory factors. The US has traditionally, through its window to the world, New York, played a major role in international finance. Russia, after the collapse of the Soviet Union quickly opened its financial systemwhile domestic lending expanded slowly.

The third observation is the share of cross-border claims (column 12) and liabilities (column 13) which are largest in the financial centres, such as SG and HK, but also in some countries where financial systems play an international role such as the UK, NL, CH and BE. As this is a BOP view, there are banks of different nationalities which perform the international business as residents. It can be assumed that Chinese owned banks in HK perform substantial cross-border business from HK rather than from mainland China as the domestic banking sector in HK is rather small.

The fourth observation is that there are still a few countries’ banks which do not have a balanced share of their external claims and liabilities. They continue net borrowing from the international banking market (column 14) as outlined above in 1.3. Countries with a high ratio are Turkey, India, Indonesia but also Finland.

Another indicator, which is not reflected in this table is the participation in the international interbank market for short term lending and borrowing[xix]. This varies greatly from country to country and can reach a substantial part of banks’ funding. While this is considered as stable funding during normal times it has been known to dry up during stress periods, such as in the aftermath of the Global Financial Crisis when banks were not sure of other banks’ exposure to the subprime market. As a result, interbank lending dried up and rates (such as overnight interest swap rate) shot up.

Finally, this article does not offer an analysis over time. This would allow a statement on the role of domestic bank financing versus cross-border bank financing over time. Indicators in the BIS study on banking in emerging markets suggest that domestic bank financing (also through foreign banks’ establishments) has expanded faster than financing from abroad[xx]. Thus bank lending continued to expand without causing cross-border capital flows.

Conclusion

While the evolution from domestic banking systems into internationally active banking systems can be documented well from the BOP, measured by cross-border business as share of total banking business, the transformation into global banks cannot be monitored through BOP statistics. It needs further statistics which are collected by BIS from the consolidated banking statistics, which presently are provided only by 31 reporting, mainly advanced economies.

In spite of these limitations, as international financial criseshave shown, banks located abroad can be significant – and volatile – sources ofcredit. Therefore, the LBS can provide a useful signal regarding potential fragilitiesin the financial system. In particular, the LBS can help monitor the build-up ofvulnerabilities associated with cross-border and foreign currency bank credit[xxi].

[i]BIS (2017): Local Banking Statistics. www.bis.org/statistics. Beforehand, the BIS statistics had to be complemented by the IMF International Financial Statistics.

[ii]In the IMF methodology, this variable is not easy to calculate as the IMF does not single out sectors but rather types of transactions. There are three categories: Foreign direct investment, portfolio investment and other investment. Most of the cross-border banking transactions are to be found in the third, but also in the second category. See IMF (2010): Balance of Payments Manual no 6. www.data.imf.org

[iii]AIF of ZJU and IMI (2017): East or west, home is best?—Are banks becoming global or local. In: IMI Review Vol 4, No 4, October www.aifzju.edu.cn

[iv]In this context deposit taking institutions

[v]The role of banks in capital outflows from China has been analysed by McCauley, R and Shu, Chang (2016): Dollars and renminbi flowed out of China. In : BIS Quarterly, March www.bis.org

[vi]The close link between the Deutsche Mark and Austrian Shilling up to the introduction of the Euro in 1999 provided such arbitrage opportunities.

[vii]One of the factors for the emergence of the Eurodollar market was the Soviet fear of a freeze of their deposits in the US. Thus they moved USD deposits to Europe, the Banqued’Europe du Nord in France.

[viii]Hu, Hong and Wooldridge, Philip (2016): International business of banks in China. In: BIS Quarterly Review, June www.bis.org/publications

[ix]See table LBS A5-CN

[x]Jeanneau, S and Micu, M (2002): Determinants of international bank lending to emerging market countries. BIS Working Papers No 112, June www.bis.org/publications

[xi]Goldberg, Linda S (2008): Understanding Banking Sector Globalisation. www.newyorkfed.org

[xii]Turner, Philip (2006): The banking systems in emerging economies: how much progress has been made. In: BIS Papers No 28, August www.bis.org/publications

[xiii]Mihaljek, Dubravko (2008): Privatisation, consolidation and the increased role of foreign banks. In: BIS Papers no 28, August www.bis.org/publications

[xiv]McCauley, Robert N, Ruud Judith S and Wooldridge, Philip D (2003): Globalising International Banking. In: BIS Quarterly Review, March www.bis.org/publications

[xv]BIS (2017): Understanding globalization. In: Annual Report 2017, chapter VI www.bis.org/publications

[xvi]BIS(2017): Consolidated banking statistics. www.bis.org/statisticsThe reporting is limited as presently only 31 countries report their banks’ cross-border business on a consolidated basis.

[xvii]Claessens, Stijn and van Horten, Neeltje (2014): The Impact of the Global Financial Crisis on Banking Globalisation. In IMF Working Papers, WP/14/197 www.imf.org/publications

[xviii]Claessens and van Horten, ibid.

[xix]BIS (2017): BIS LBS captures 93% of cross-border interbank business. In: Statistics Bulletin, September www.bis.org/publications

[xx]See table 4 in Mihaljek, Dubravko, ibid.

[xxi]BIS (2017): ibid

In bn USD at the end of 2Q2017

Sources: BIS LBS, PBOC, BNM, TCMB, FED *total is not the sum of components due to unallocated items. LC=local currency, FC=foreign currency

Section 2: Observations on the domestic versus cross-border banking statistics

The first observation to be made is the absolute size of the total claims (columns 4 and 6) and liabilities (columns 9 and 11). The size of bank lending is largest in China and Japan, both countries dominated by bank finance rather than capital markets. The US figure is much smaller as capital markets play a more important role.

The second observation is that lending in big countries is usually dominated by domestic lending, with cross-border business playing a small role. Examples are Brazil, China, India, Indonesia and Mexico. Other big countries have individual explanatory factors. The US has traditionally, through its window to the world, New York, played a major role in international finance. Russia, after the collapse of the Soviet Union quickly opened its financial systemwhile domestic lending expanded slowly.

The third observation is the share of cross-border claims (column 12) and liabilities (column 13) which are largest in the financial centres, such as SG and HK, but also in some countries where financial systems play an international role such as the UK, NL, CH and BE. As this is a BOP view, there are banks of different nationalities which perform the international business as residents. It can be assumed that Chinese owned banks in HK perform substantial cross-border business from HK rather than from mainland China as the domestic banking sector in HK is rather small.

The fourth observation is that there are still a few countries’ banks which do not have a balanced share of their external claims and liabilities. They continue net borrowing from the international banking market (column 14) as outlined above in 1.3. Countries with a high ratio are Turkey, India, Indonesia but also Finland.

Another indicator, which is not reflected in this table is the participation in the international interbank market for short term lending and borrowing[xix]. This varies greatly from country to country and can reach a substantial part of banks’ funding. While this is considered as stable funding during normal times it has been known to dry up during stress periods, such as in the aftermath of the Global Financial Crisis when banks were not sure of other banks’ exposure to the subprime market. As a result, interbank lending dried up and rates (such as overnight interest swap rate) shot up.

Finally, this article does not offer an analysis over time. This would allow a statement on the role of domestic bank financing versus cross-border bank financing over time. Indicators in the BIS study on banking in emerging markets suggest that domestic bank financing (also through foreign banks’ establishments) has expanded faster than financing from abroad[xx]. Thus bank lending continued to expand without causing cross-border capital flows.

Conclusion

While the evolution from domestic banking systems into internationally active banking systems can be documented well from the BOP, measured by cross-border business as share of total banking business, the transformation into global banks cannot be monitored through BOP statistics. It needs further statistics which are collected by BIS from the consolidated banking statistics, which presently are provided only by 31 reporting, mainly advanced economies.

In spite of these limitations, as international financial criseshave shown, banks located abroad can be significant – and volatile – sources ofcredit. Therefore, the LBS can provide a useful signal regarding potential fragilitiesin the financial system. In particular, the LBS can help monitor the build-up ofvulnerabilities associated with cross-border and foreign currency bank credit[xxi].

[i]BIS (2017): Local Banking Statistics. www.bis.org/statistics. Beforehand, the BIS statistics had to be complemented by the IMF International Financial Statistics.

[ii]In the IMF methodology, this variable is not easy to calculate as the IMF does not single out sectors but rather types of transactions. There are three categories: Foreign direct investment, portfolio investment and other investment. Most of the cross-border banking transactions are to be found in the third, but also in the second category. See IMF (2010): Balance of Payments Manual no 6. www.data.imf.org

[iii]AIF of ZJU and IMI (2017): East or west, home is best?—Are banks becoming global or local. In: IMI Review Vol 4, No 4, October www.aifzju.edu.cn

[iv]In this context deposit taking institutions

[v]The role of banks in capital outflows from China has been analysed by McCauley, R and Shu, Chang (2016): Dollars and renminbi flowed out of China. In : BIS Quarterly, March www.bis.org

[vi]The close link between the Deutsche Mark and Austrian Shilling up to the introduction of the Euro in 1999 provided such arbitrage opportunities.

[vii]One of the factors for the emergence of the Eurodollar market was the Soviet fear of a freeze of their deposits in the US. Thus they moved USD deposits to Europe, the Banqued’Europe du Nord in France.

[viii]Hu, Hong and Wooldridge, Philip (2016): International business of banks in China. In: BIS Quarterly Review, June www.bis.org/publications

[ix]See table LBS A5-CN

[x]Jeanneau, S and Micu, M (2002): Determinants of international bank lending to emerging market countries. BIS Working Papers No 112, June www.bis.org/publications

[xi]Goldberg, Linda S (2008): Understanding Banking Sector Globalisation. www.newyorkfed.org

[xii]Turner, Philip (2006): The banking systems in emerging economies: how much progress has been made. In: BIS Papers No 28, August www.bis.org/publications

[xiii]Mihaljek, Dubravko (2008): Privatisation, consolidation and the increased role of foreign banks. In: BIS Papers no 28, August www.bis.org/publications

[xiv]McCauley, Robert N, Ruud Judith S and Wooldridge, Philip D (2003): Globalising International Banking. In: BIS Quarterly Review, March www.bis.org/publications

[xv]BIS (2017): Understanding globalization. In: Annual Report 2017, chapter VI www.bis.org/publications

[xvi]BIS(2017): Consolidated banking statistics. www.bis.org/statisticsThe reporting is limited as presently only 31 countries report their banks’ cross-border business on a consolidated basis.

[xvii]Claessens, Stijn and van Horten, Neeltje (2014): The Impact of the Global Financial Crisis on Banking Globalisation. In IMF Working Papers, WP/14/197 www.imf.org/publications

[xviii]Claessens and van Horten, ibid.

[xix]BIS (2017): BIS LBS captures 93% of cross-border interbank business. In: Statistics Bulletin, September www.bis.org/publications

[xx]See table 4 in Mihaljek, Dubravko, ibid.

[xxi]BIS (2017): ibid