Mark Sobel: Scepticism on Second Plaza Accord

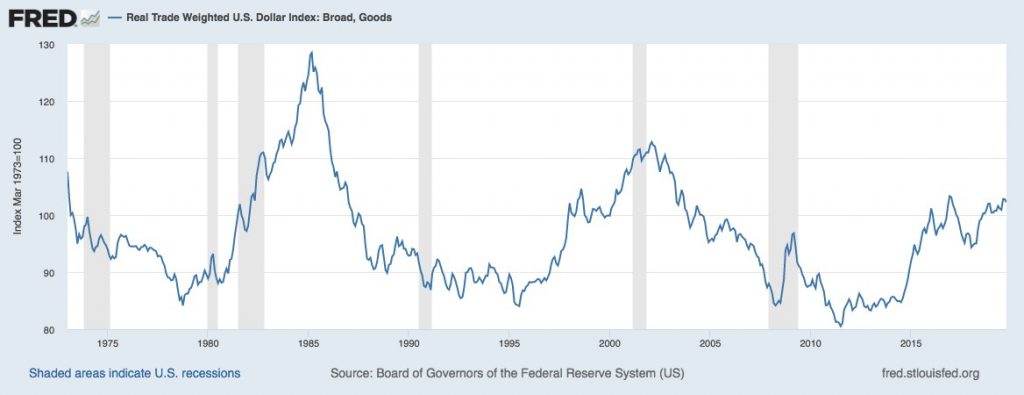

2019-11-14 IMI As a pact between G5 finance ministries and central banks, Plaza predated the advent of the European Central Bank and China’s rise. Any deal now would require a different, less cohesive set of actors. While the US remains the world’s largest economy (using market exchange rates), its hegemonic role has lessened. Washington led the effort on Plaza, but these days it is uncertain if it would or could lead, let alone if others would follow the US.

Since the 1985 accord, thinking on policy coordination has changed. Except in extreme times, the best contribution countries could make to sound global economic functioning was to keep their own houses in order. Intervention, especially if sterilised, had little impact. Monetary policy should achieve domestically driven mandates, including price stability, and not target exchange rates or current account positions. Fiscal fine-tuning was difficult given administrative lags, and often the need to pursue consolidation. This thinking hindered Plaza-type co-operation.

The Plaza accord urged countries to resist protectionism, just as the 2008 G20 Washington summit communiqué urged countries to refrain from protectionist measures.

That position was oft-repeated in G20 communiqués, but then dropped during the Trump administration. The US president’s trade wars have helped foster a risk-off market environment, which boosts the dollar. The end to trade wars would probably lead to dollar depreciation, but there is no consensus yet on Washington’s willingness to do so.

Brussels and Japan have evinced little concern about disorderly exchange markets or exchange rate misalignments. They would probably not agree with Trump that their exchange rates are substantially undervalued, and they view the dollar’s strength as understandable in light of relative US economic outperformance and the president’s trade threats.

Critically, it is unclear what could constitute a package of fundamental economic commitments to produce orderly non-dollar appreciation. The elements might conceivably be there, but the will or ability to follow through is questionable. Markets are not disorderly. The US, European Central Bank and Japan practice free floating for all intents and purposes, and there would be little appetite for intervention.

In principle, US fiscal consolidation could reduce the country’s current account deficit and lessen the need for foreign capital inflows. However, the executive and legislative branches have shown little capacity or desire to run responsible budgetary policies.

Fiscal expansion in Germany and the New Hanseatic League, a grouping of eight fiscally conservative EU governments, could boost demand and take some burden off of monetary policy. But despite the beginnings of shifting German rhetoric, the country seemingly remains committed to its zero deficit ‘schwarze Null’ policy and debt brake.

With anaemic growth, and inflation consistently below target, euro area monetary policy normalisation seems unlikely to occur any time soon.

While China has some fiscal space, monetary policy will probably remain accommodative in the face of a highly leveraged and slowing economy. China has an interest in renminbi stability, especially given the potential for capital outflow, but it does not wish to reduce its reserves below $3tn.

Cohesion is lacking among the major players as they pursue domestic priorities. The US and China may seek to establish a truce, but there is little trust between the two and geopolitical competition is here to stay. Rising European nationalism and populism stymie efforts to advance the Union.

The 2008 financial crisis proved that in dire straits, countries can coordinate. But the sense of cohesion needed for a ‘Plaza 2’ is sorely lacking.

As a pact between G5 finance ministries and central banks, Plaza predated the advent of the European Central Bank and China’s rise. Any deal now would require a different, less cohesive set of actors. While the US remains the world’s largest economy (using market exchange rates), its hegemonic role has lessened. Washington led the effort on Plaza, but these days it is uncertain if it would or could lead, let alone if others would follow the US.

Since the 1985 accord, thinking on policy coordination has changed. Except in extreme times, the best contribution countries could make to sound global economic functioning was to keep their own houses in order. Intervention, especially if sterilised, had little impact. Monetary policy should achieve domestically driven mandates, including price stability, and not target exchange rates or current account positions. Fiscal fine-tuning was difficult given administrative lags, and often the need to pursue consolidation. This thinking hindered Plaza-type co-operation.

The Plaza accord urged countries to resist protectionism, just as the 2008 G20 Washington summit communiqué urged countries to refrain from protectionist measures.

That position was oft-repeated in G20 communiqués, but then dropped during the Trump administration. The US president’s trade wars have helped foster a risk-off market environment, which boosts the dollar. The end to trade wars would probably lead to dollar depreciation, but there is no consensus yet on Washington’s willingness to do so.

Brussels and Japan have evinced little concern about disorderly exchange markets or exchange rate misalignments. They would probably not agree with Trump that their exchange rates are substantially undervalued, and they view the dollar’s strength as understandable in light of relative US economic outperformance and the president’s trade threats.

Critically, it is unclear what could constitute a package of fundamental economic commitments to produce orderly non-dollar appreciation. The elements might conceivably be there, but the will or ability to follow through is questionable. Markets are not disorderly. The US, European Central Bank and Japan practice free floating for all intents and purposes, and there would be little appetite for intervention.

In principle, US fiscal consolidation could reduce the country’s current account deficit and lessen the need for foreign capital inflows. However, the executive and legislative branches have shown little capacity or desire to run responsible budgetary policies.

Fiscal expansion in Germany and the New Hanseatic League, a grouping of eight fiscally conservative EU governments, could boost demand and take some burden off of monetary policy. But despite the beginnings of shifting German rhetoric, the country seemingly remains committed to its zero deficit ‘schwarze Null’ policy and debt brake.

With anaemic growth, and inflation consistently below target, euro area monetary policy normalisation seems unlikely to occur any time soon.

While China has some fiscal space, monetary policy will probably remain accommodative in the face of a highly leveraged and slowing economy. China has an interest in renminbi stability, especially given the potential for capital outflow, but it does not wish to reduce its reserves below $3tn.

Cohesion is lacking among the major players as they pursue domestic priorities. The US and China may seek to establish a truce, but there is little trust between the two and geopolitical competition is here to stay. Rising European nationalism and populism stymie efforts to advance the Union.

The 2008 financial crisis proved that in dire straits, countries can coordinate. But the sense of cohesion needed for a ‘Plaza 2’ is sorely lacking.