Raphael Lam: Climate Crossroads: Fiscal Policies in a Warming World

2023-10-31 IMIThis is based on the speech by Raphael Lam on the Macro-Finance Salon (No. 215) held at IMI on October 24, 2023.

Raphael Lam, Deputy Division Chief, Fiscal Affairs Department, IMF

Thank you very much. I will start the presentation. So we just launched October 2023 of Fiscal Monitor, just two weeks ago. And then this topic is on the climate crossroads. What kind of impact does it have on the public finances in different areas from the sustainability angle? How much does it cost the government to achieve some of the policies? So this would be more focused on the public finance area on top of the fund that has been developing Excel into different areas on the climate policies.

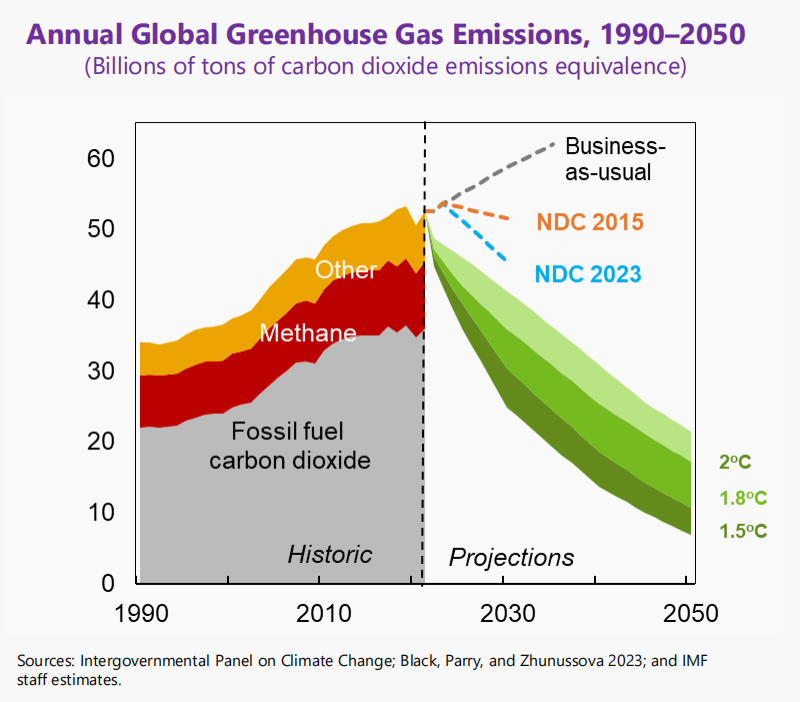

So to start with, certainly, I mean, as everyone would be aware that now countries have been starting to implement some of the policies in order to reduce their emissions. However, if you look at the left-hand side, what countries agreed in the Paris Agreement in 2015 is to reduce emissions to about net zero by the mid-century 2050. By those measures, if the purpose is to reduce global warming to keep the rise in the global temperature just by around 1.5% to 2% degrees relative to the industrial level. So that will be the green trajectories that countries will need to do in order to achieve climate goals.

However, although countries have started the measures, on average, they are falling short of the need that to achieve net zero emissions by mid-century.

You can see the two dotted lines called the Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) both the 2015 version as well as the 2023 version, which is the latest one that we estimated, somewhat still far away from the gap that we needed to close by the midcentury. This means that although countries are making efforts, as we can see that we are already making efforts from the orange line to the blue line, it is still far away to get into the green corridor. So certainly more actions are needed in order to close or narrow the implementation as well as the ambition gap. So these will be the ideas that countries would definitely need to do more.

And I think there's increasing awareness of the public of policymakers and then both the domestic level as well as the international level. Here I think China is also very proactive in committing itself to a range of climate goals, not just in emissions but also in other areas.

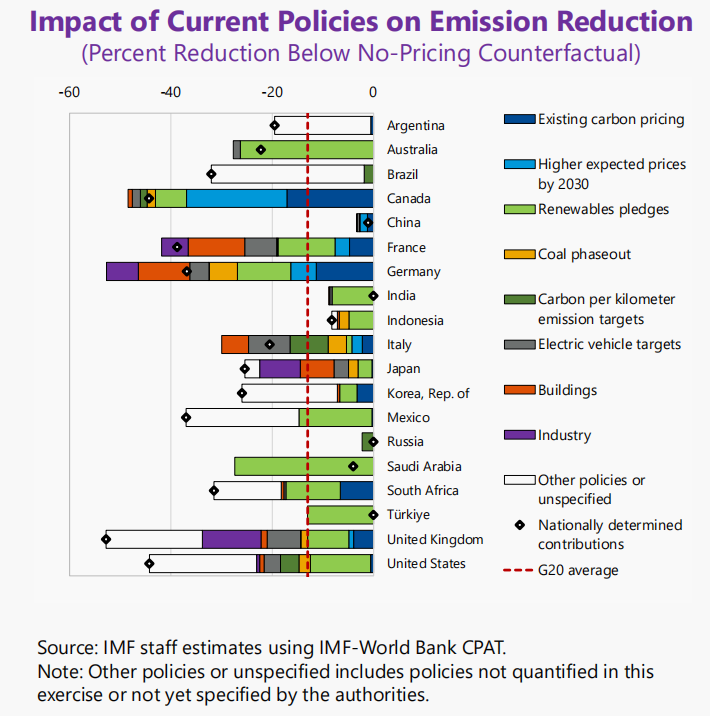

However, we see that on the right side, countries are pursuing different types of kind of policies with varying degrees of success. Here we focus on the G20 economies both for advanced as well as emerging markets. As you can see the bars, which are denoted. They are doing in terms of different sectors rarely quite significantly across. So for instance, in China, over there, the blue bar is very obvious then we take in terms of the current policies for reducing emissions. But on average the G 20s is committed only to reducing 13% of the regions which is a red dotted line there, much short of the goals that are required to achieve the net zero emission. Some countries are doing more, for example, Canada, or maybe France and Germany. So there are different degrees of success in these contexts, as you can see.

So the key questions that we raise in the Fiscal Monitor will be: If countries are pursuing different types of policies and if they want to scale it up in order to get the emissions down to the green corridor, would that be feasible to achieve it by just spending more? So would it be good for public finances? Would it be good to achieve a net zero emission by spending more?

The second question is that we want to understand better what countries can do in terms of the kind of policies. There are different sets of policies that could be used to reduce emissions like by promoting green cars or electronic cars, you can provide subsidies. The government can undertake a lot of investment or a charge of price on carbon emissions. So how can policymakers design some of the policies, balancing the political side and the public finance impact as well as finding a way to that is more cost-effective in delivering the objectives?

And then the third one is that the private sector needs to play a bigger role in terms of the decarbonization efforts. Can the government do more to facilitate the green transition among the firms? So it's not just the role of the private sector and the public sector, but it also needs a lot of involvement on the private side, both firms and households. So to review the results, let me give you a quick overview.

So we, the monitor would probably give out a conclusion that we cannot just scale up the spending policies. But some countries have started to do it. For example, in the last couple of years, the US has brought out the Inflation Reduction Act. The European Union has proposed the Green Deal industrial policies. We're spending a little bit more on the public side in order to reduce the gap in emissions. But in our assessment, some of these measures, if we scale it up further, tend to be inefficient, but at the same time, to put that sustainability at risk. I will go back to that in some of the analysis. The monitor would find that the only way they could kind of achieve the best mix of the policies would be we find a way that includes both on the spending side, but also some revenue measures in which could make a good balance of public financing.

And particular we consider that carbon pricing should play a more central role or integral within the overall policy package. We see that in the last part, firms still play a role in terms of decarbonization. And this is important for the government to withdraw the regulations. As for some of the fiscal incentives, you are not just to encourage firms to invest in non-carbon technology. Certainly, in recent measures of the big subsidies that are rolled out by countries, we need to be involved carefully so that it doesn't stop some of the competition among firms across borders but at the same time encourage the firms to invest in signal carbon technology.

1. Can countries scale up spending measures to reach climate goals?

So maybe we start with the first questions to show you some of the results of why we consider that the countries cannot just scale current spending-based policies.

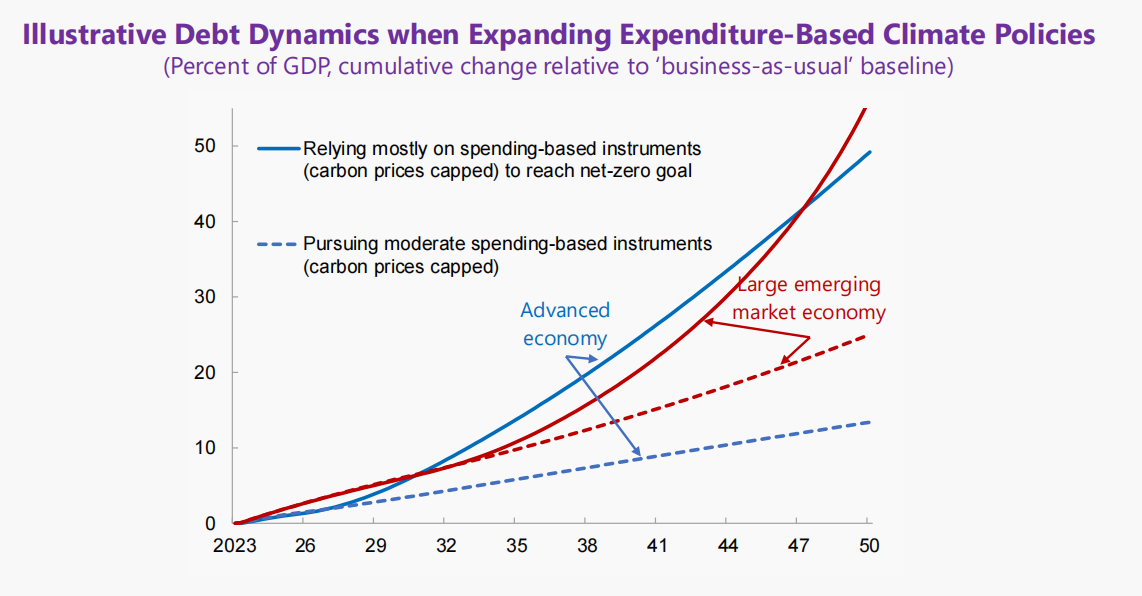

Here we used a dynamic general equilibrium model, a modeling framework that includes the effects if the government spends more, what will be the impact on growth, inflation as well as time with emission based on some of the parameters that we use in the literature. So the model is kind of a dynamic general medium and then we consider different scenarios. The scenarios we consider as for both the advanced economy as well as the large emerging market economies. Which are shown in the blue and red lines in the chart. The one that we want to illustrate is what if the government's scaling up in order to achieve net zero emissions by midcentury, meaning that on average countries will need to spend by an additional 2% of GDP per year in order to achieve the reduction of emission, assuming that the carbon pricing is kind of capped as about $75. For advanced economies and emerging markets, at $45 for carbon emissions. So this is a relatively low level, although it is higher than the current level, it is relatively low in order to achieve massive emissions.

So this picture illustrates the impact on public finance measured by the debt to GDP. As you can see in both the advanced economy and in large emerging markets, the debt would essentially roll up or expand at a very rapid pace, by about 45% to 50% of GDP by 2050, relative to the business-as-usual baseline. So basically relative to the baseline we have, we will see an additional 45% to 50% of GDP increase if the countries scale up some of the spending measures in order to reach the net zero emissions goal. That's certainly not sustainable for many countries because countries already have a very high debt level. So this is the situation certainly is not sustainable from the financial viewpoint.

The second set of scenarios illustrated in the dotted line here shows a different picture. Which is essentially the government spends. That's the same as what it is now, a little bit higher. But at the same time, keep the carbon pricing effects. So there's no carbon price increase for moderate actions to increase in terms of spending. Because of moderation, you can see that debt increases relatively mild, but at the same time, we will not achieve net zero emissions by 2050. So it's failing to reach the climate goals. The reduction of efficiency is only by about 30% to 40%, relative to the necessary degree that is required to reach net zero. So this is the situation that we face. For a lot of governments, is how to balance public finance while advancing the kind of policies.

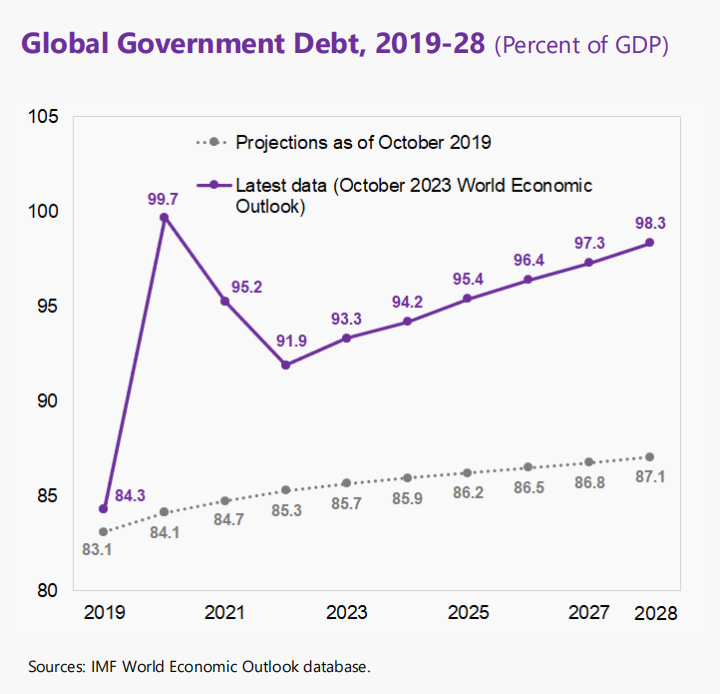

Here we show the latest illustrations of real projections that maybe some of you are aware of. Not only is the increase in public debt notable, but it will put it at an unsustainable level if countries scale up spending. The government debt already right now is at a very high level. It is expected to reach 93% of GDP for the global public debt by the end of this year. You can see after the two-year debt decline from 2021 to 2022, it started to pick up again in our forecast. And the pace of pickup is at about 1% of GDP per year over the medium term. And it would approach 100% of GDP by the turn of this century. So this would be significant if governments want to pursue a common policy by increasing debt. Not only that, you can see the takeoff in the pace of the debt outlook has worsened than the pre-pandemic projections.

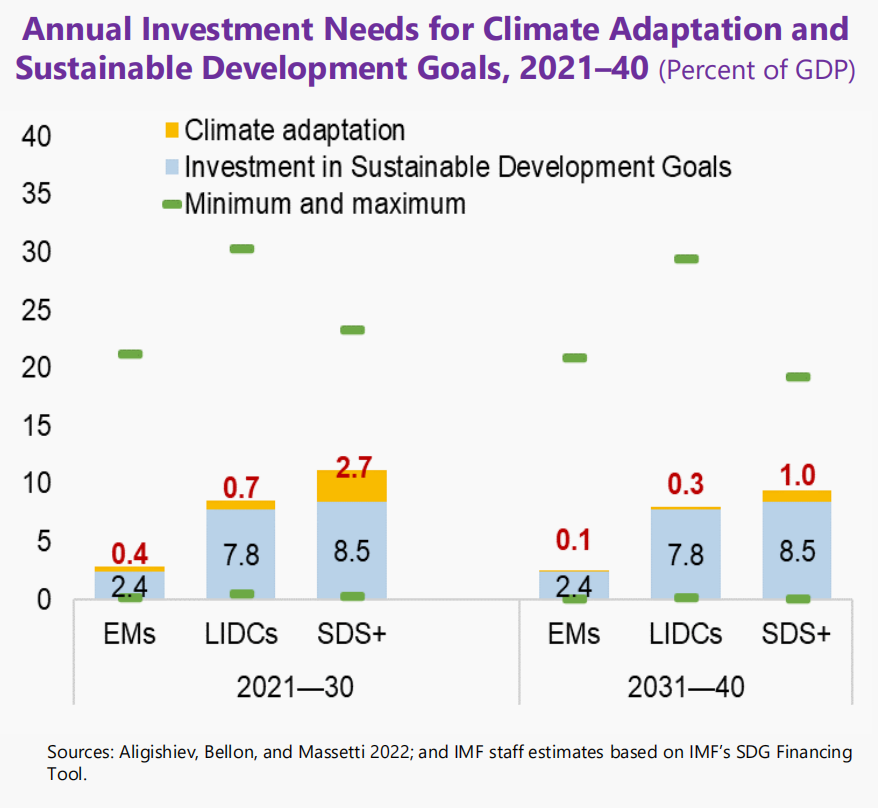

But see that the pace of the debt increase will be much higher than people's projections. At the same time, a lot of the emerging markets as well as the low-income countries would not only face the problem of the mitigations, but they also need to adapt to climate change. They also need to have priorities to meet their sustainable development goals, for instance, on education, healthcare, sanitation, infrastructure, etc. This would all cost money in order to achieve it. And we have some estimates in the Fiscal Monitor to put a number on it. How big it is and the numbers are very sizable.

For instance, for this decade, it is estimated that the emerging markets that have low-income countries need to spend an additional 0.4% and 0.7% of GDP per year. And this is certainly sizable. And for the small states, small developing states, meaning that it's somewhat exposed to all kinds of risks, they would need to spend a much higher level. Similarly for the investment to a Sustainable Development Goal, there is also very sizable. This would essentially mean that public finance is already scratched in terms of reaching some of these development goals while at the same time delivering an additional objective on all kinds of policies. So certainly countries will be facing a lot of problems. The monitor will frame it as governments or the policymakers are facing a policy trend, meaning that they will try to balance different objectives. At one goal, they want to achieve the climate goal by reducing emissions and building resilience against climate risk. Alongside, we are keeping public debt in a sustainable way so that we contain sovereign debt distress and building buffers for future shops that certainly would already be kind of a very challenging situation.

The issue is certainly the government has some options to raise revenue either to increase tax because a lot of tax as the capacity or a lot of potential according to a recent estimate by our colleagues at the Fiscal Affairs Department. Or you want to increase some of the expensive pricing on carbon emissions. In China, it is the carbon tax or emission trading system. However, this would relax some of these constraints in order to reach out to climate goals and keep public finances on track. Most of those revenue measures are politically less feasible or the public will usually dislike them. We usually dislike those additional metrics on taxation. So certain political constraints would be important considering the situation here.

2. How to strike a balance on the policy trilemma?

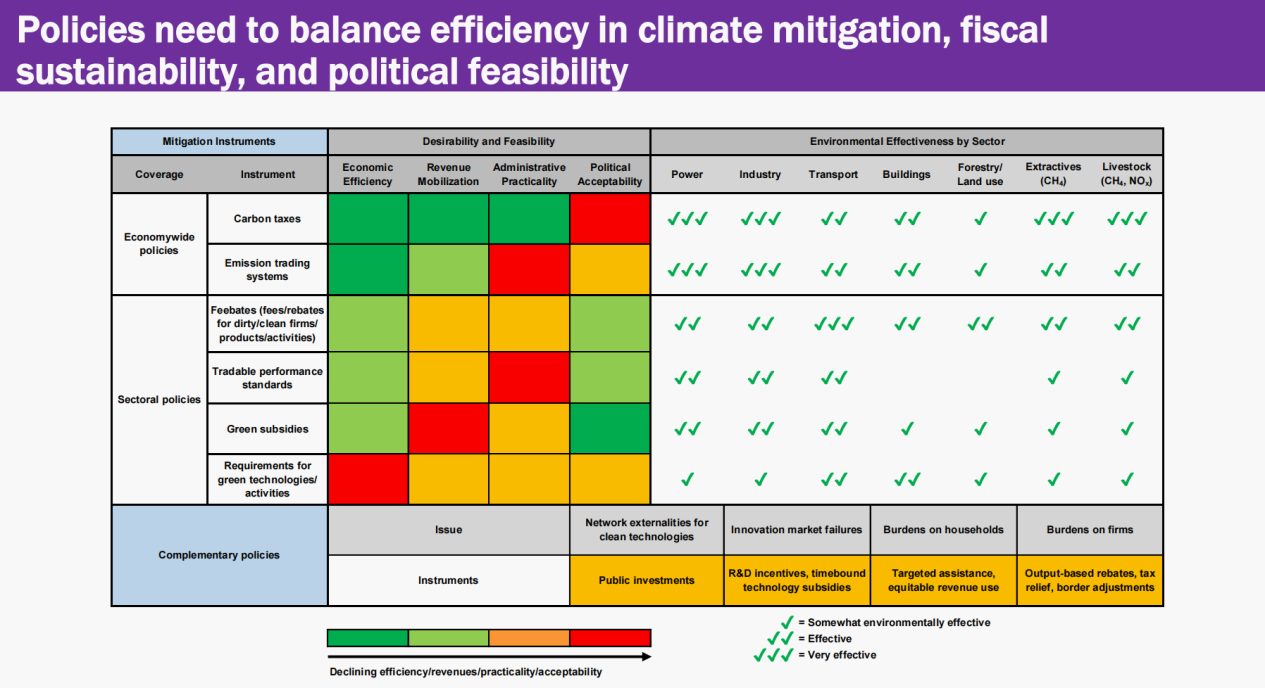

So essentially the government will need to face the policy trend by striking a balance between these two, between the three carriers. So in terms of the monitor, we are trying to understand better how the government is doing it, and should try to strike a balance between the triangle that I just illustrated. The way that the monitor didn't demonstrate is that there are possible ways. It's difficult, but it's possible to achieve balance here. Basically, it shows the balance between the efficiency of measures, meaning that there are some measures that could achieve climate mitigation in a much more efficient way. We also want to balance fiscal sustainability and also to achieve results that are politically feasible.

Here this is a relatively complex table. Let me walk you through it. But it essentially shows different types of instruments that are shown on the left side. According to different criteria that we just laid out, whether they are cost-effective, whether they are able to mobilize revenues, whether they are easy to be administered, and whether they are politically acceptable. So different categories and in different colors. On the green side, it is easier to do so. On the right side, it means that it is more difficult.

We also show the effectiveness according to different sectors, power industries, transport, buildings, and also in different categories. Some are easier in a couple of days. And in terms of emissions, some are much more difficult in another setting. So you could think of cement industries. Or you could think of aviation if you travel. And also causes sort of common issues. So different types of instruments will have different effectiveness in these areas.

So from this table, we could illustrate that carbon taxes are usually a very efficient way to reduce emissions because they affect a lot of incentives at a quarter range, encourage households and firms to preserve energy use or to move to a lower polluting technology, or to essentially facilitate the transitions to a green energy source.

However, it's usually politically feasible. A lot of the country's citizens are insisting on those measures that are going to increase carbon pricing. So it is important to think of these policy packages as consisting of different instruments. Some of them may need to include green subsidies to support firms, particularly in areas that have a lot of network externalities or market failures, then the green subsidies will be used. So overall, the Monitor gives us some country examples along these dimensions as well as a kind of brand instrument for introducing different criteria. Ultimately we want to kind of reach out to find an optimal solution to achieve carbon reduction while meeting some of the tremendous difficulties.

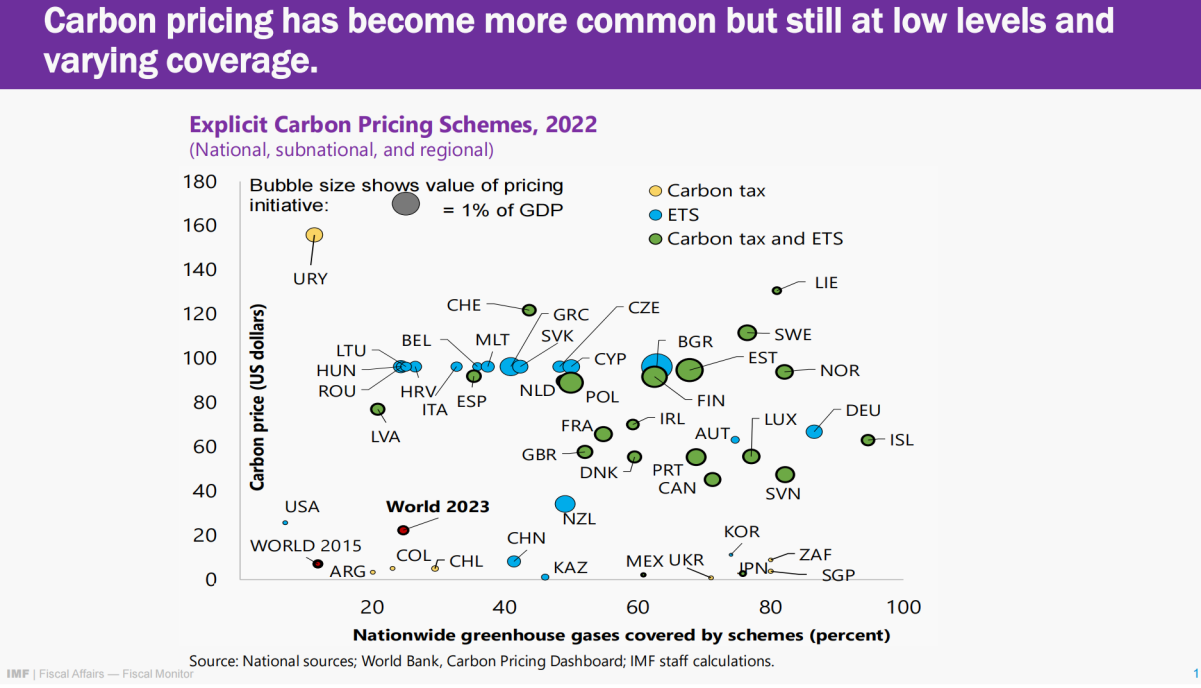

Talking about carbon pricing, there are a lot of receptions, but overall we consider that carbon price has become much more common over the last decade. So right now, as of our analysis in 2022, about 49 countries have explicit carbon pricing schemes, either in the form of carbon taxes or in the form of Emissions Trading System (ETS), which is the blue dot. But you could see that although a lot of countries have adopted it, the overall level is still at a very low level. It will change, increase about $20 per time, but it's already a significant rise. When they keep to the world in 2050, which is about $5 per ton.

But only so far, less than a quarter of the global emissions are covered under the carbon pricing scheme. So it's not a horizontal axis. Not only that, you could see that in a lot of the large economies, such as the US, China, and Japan, the level of carbon pricing is still at a relatively low level, meaning that there's a lot of scope to generate revenue if we have a pricing.

Understanding it may not be very politically acceptable in any case. But the good deal is that countries are starting to have carbon pricing schemes. And on top of these 49 countries, we have also observed that maybe 20 countries are also considering having explicit pricing schemes. That could be implemented in the next couple of years. So in terms of the appropriate mix of the fiscal policies, we have done some analysis in the Fiscal Monitor by illustrating the implications using a model-based analysis. The model we use is similar to the one I introduced earlier, which is based on the dynamic general equilibrium model. So it accounts for all the impact of government policies affecting the micro variables and feedback effects coming from that.

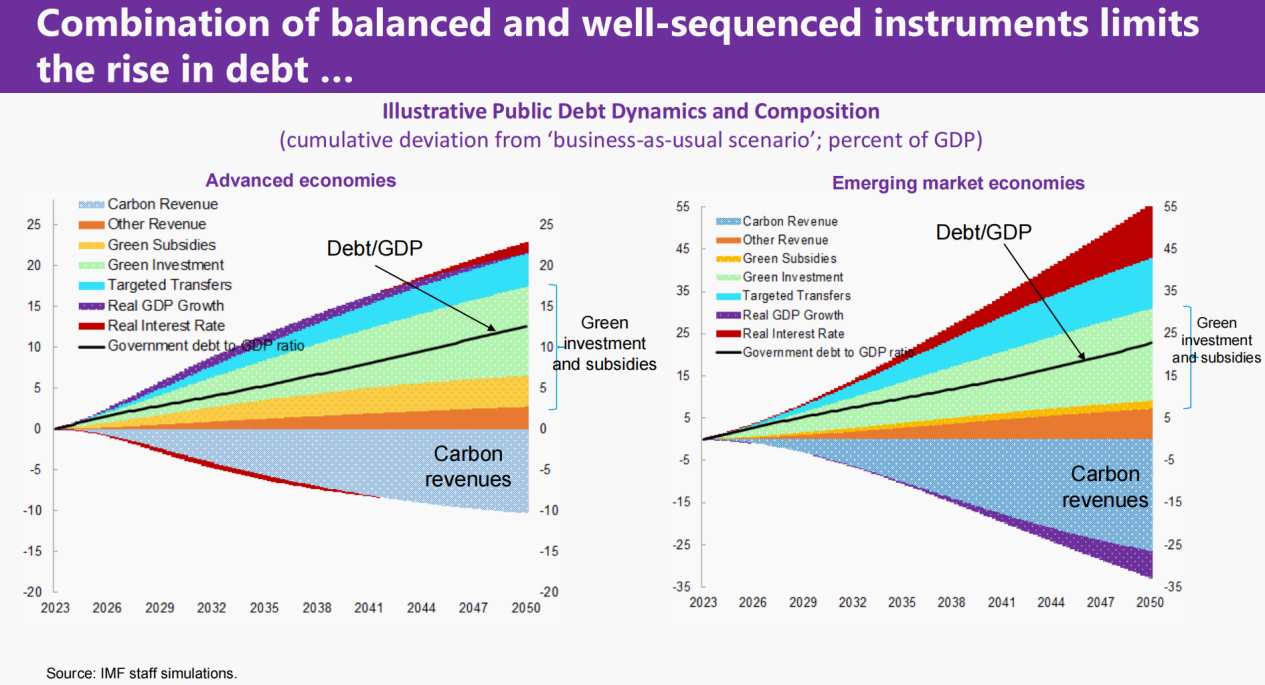

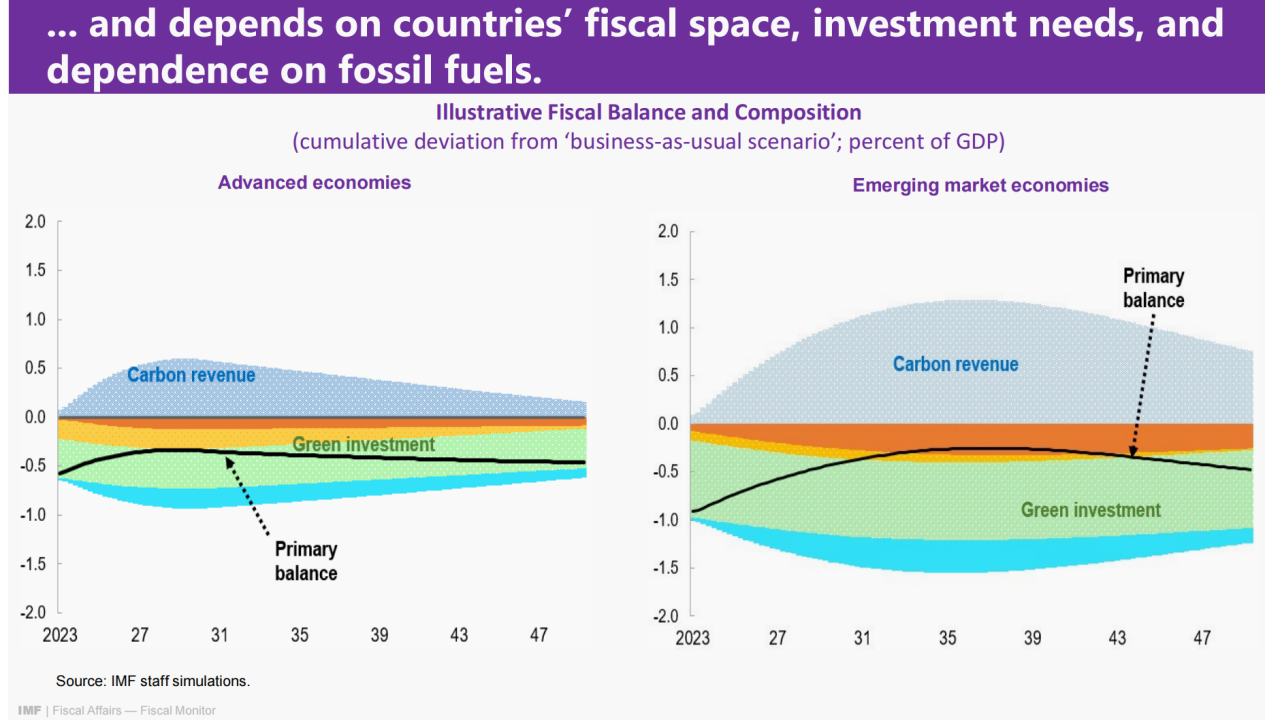

So this is the most advanced analysis in the whole presentation on the Fiscal Monitor. I will walk you through these two charts. Here we basically want to understand the impact on public finances of different illustrations of climate policies. So in the chart, the debt to GDP ratio is shown in the black line. So on average, you can see that countries pursue different types of policies that will have an impact on debt to GDP ratio. And it is measured additionally on top of the business-as-usual scenario.

The primary policies that we consider have different elements. One is certainly about green investment meaning that the public sector undertakes the investment. You can imagine it's an electricity great. Imagine there's a big scale of investment in the green sector. We also consider some of the subsidies which are indicated in the orange or yellow area. So these are the two main sources of government spending in order to promote the transitions to the green sector, in order to reduce efficiency. The estimates vary across countries certainly and we are using some of the estimates obtained from the International Energy Agency in this analysis. For advanced economies, on average, it is about 0.4% to 0.5% of GDP. And for emerging markets, it is about 0.7% to 0.8% of GDP per year on average.

Another important set of the policy makes as we indicate will be carbon pricing, which indicator is carbon revenue. And it has results in keeping the debt build-up in a more contained way by reducing the debt increases.

So on average, this is a significant source of tax revenue that could motivate climate reduction, but also at the same time, generate revenues for adults. As you can see from the advanced economies here, the Carbon Revenue scheme pack is quite significant. Although I mean the peak of carbon revenues are going to be controlled in about the mid-2030s over the longer term. So all these implications would either have an effect on that, increasing it, or decreasing it. So the use of a dynamic general equilibrium model would also have additional features, not just by putting these samples together, but also account for the indulgence effect coming from the interest rate, which is the red part, as well as the purple one on growth impact. So if countries spend more, it could be promoted to growth. Whereas some of the taxes may also contain rising growth.

But overall, as the simulation illustrated, the growth impact of all these carbon policies which are well designed, tends to be minimal, which is in line with some of the literature that we have indicated or found over the last couple of years, in which case that as long as carbon pricing is introduced. However, with some mechanisms recycling direct use, the growth impact tends to be relatively neutral rather than an earthquake disease. And we have shown some of the literature results in the fiscal market.

The important part here, as you can see on average, the debt would rise by 10% to 15% of GDP by 2050, which is a notable amount. At the same time, we do look at the emerging market economies, which we consider the average of the large emitters in G20 countries. The magnitude of increases is relatively simple. But at the same time, if you look at the individual components, they look quite different. For instance, the red part which is coming from the interest rate effect. For instance, the red part, which is the interest rate effect, is notably much higher in emerging markets than in advanced countries, meaning that, because debt in emerging markets tends to be more vulnerable to changes in interest rate, in which case if the emerging market economy has a higher debt, interest rate tends to be higher, the foreign cost has to be higher and that people have a deteriorating effect on debt buildout.

Similarly, the investment needs for free investment are higher, as we mentioned before. Drawing from the estimate in literature, carbon revenues are also much bigger than the advanced economy, suggesting that they have higher revenue potentials, given that they're continuing to have increasing carbon emissions over the medium term as they grow and develop. By 2030, by some estimates, emerging markets will account for about 70% of global emissions.

So let me illustrate the impact on the deficit. These two charts are exactly the same as before but instead of showing that increases. These two charts show the flow, which has an impact on the annual budget measure in terms of the primary balance. So essentially a negative means a debt. By having the same scale in the two charts, one could see that the comparison between the emerging markets and advanced economies becomes much clearer. As I mentioned, carbon revenue is much bigger even though the carbon prices per ton of carbon emissions are much lower in emerging markets. Here we assume it will reach about $150 per ton by the end of 2050. Whereas, the advanced economies will be over $200 by the mid-century. And then you can see that they have a different peak of the shape pattern. Within advanced economies, the peak is much earlier via the turn of the decade. Whereas the emerging markets will be around the mid-2030s. So the role of carbon revenue potentials will eventually subside because by then carbon emissions, the tax base will be smaller even though the pricing continues to increase. And of course, because the important part is also the shape of the deficit path. Given that most of the public investment and green subsidies are frontloaded, the initial impact on the deficit is generally higher. Although, on average, it is about 4% until 2050. This level of debt increase and deficit for some advanced economies may be manageable, particularly for those that have fiscal space. But for a lot of emerging markets, especially developing countries, there will be great challenges given that they already have bad problems. Interest rates are going to rise. In addition, resources that may be needed to devote to climate mitigation would certainly be a big challenge for a lot of emerging markets. That would justify some of the indications mentioned by rural development. They need to have stronger global cooperation, making sure some of the financing will be able to channel issues support in the emerging markets or developing countries in climate mitigation.

The fund has established some of the facilities as a first step, but certainly, much more needs to be done by the global community. So this will be the main key results of the Fiscal Monitor looking at public finance impact.

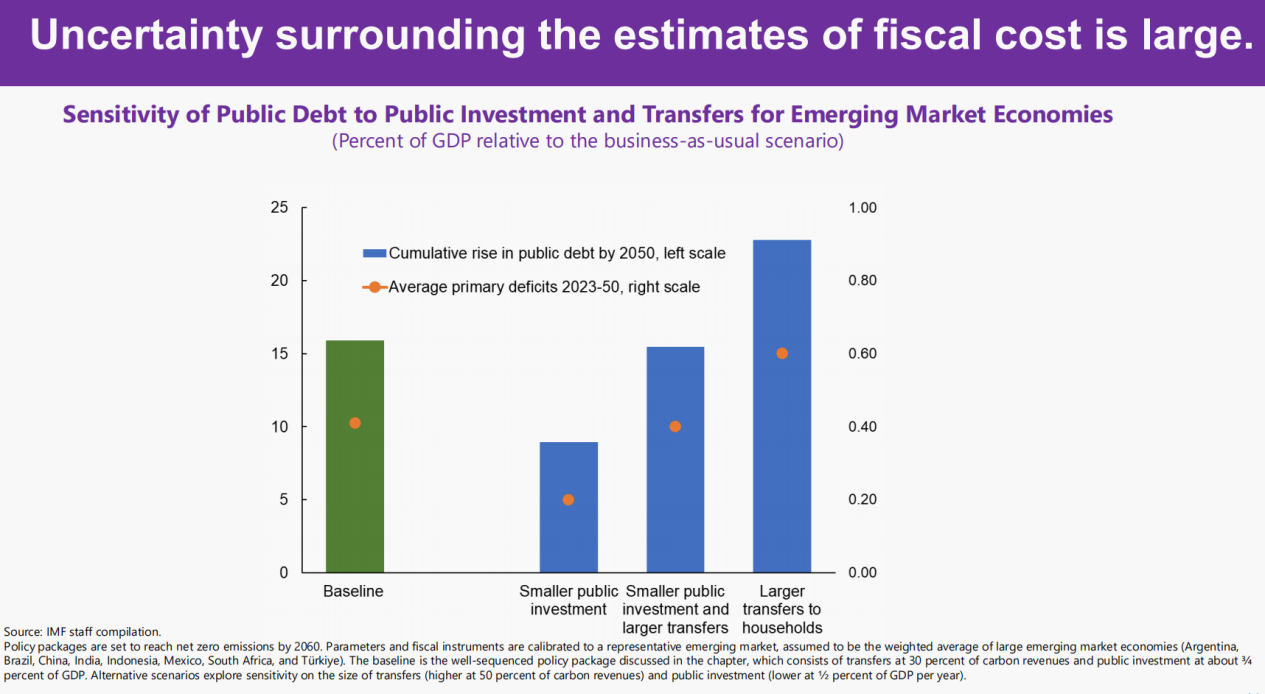

So there are some of these estimates that we introduce 10% to 15% of GDP that increases would vary according to some of the assumptions we made. The estimates of the fiscal cost could be very big because we are forecasting over a long time horizon until 2050. In the costs, a lot of things could have changed, but we illustrated some of the sensitivity analysis with different degrees of macro net increase.

For instance, we show that on the baseline for emerging markets countries, it's about 10% to 15%, slightly higher than 15% by 2050. But if we had a smaller public investment, the debt increase would likely be smaller.

That would be the case because some countries may already have invested in green investment and the additional lease may be smaller. In particular, one could reduce their investment in the fossil sector, and use the same money to invest in the green sector. So that net investment could be smaller than we have put in the baseline. Then certainly that would help the public that increase. But at the same time, if we transfer a lot more money to households in order to protect the vulnerable ones, the extra fiscal cost may give rise to a much higher debt increase of about 20% to 25%. So the main purpose of showing this analysis is that there is a lot of uncertainty surrounding it.

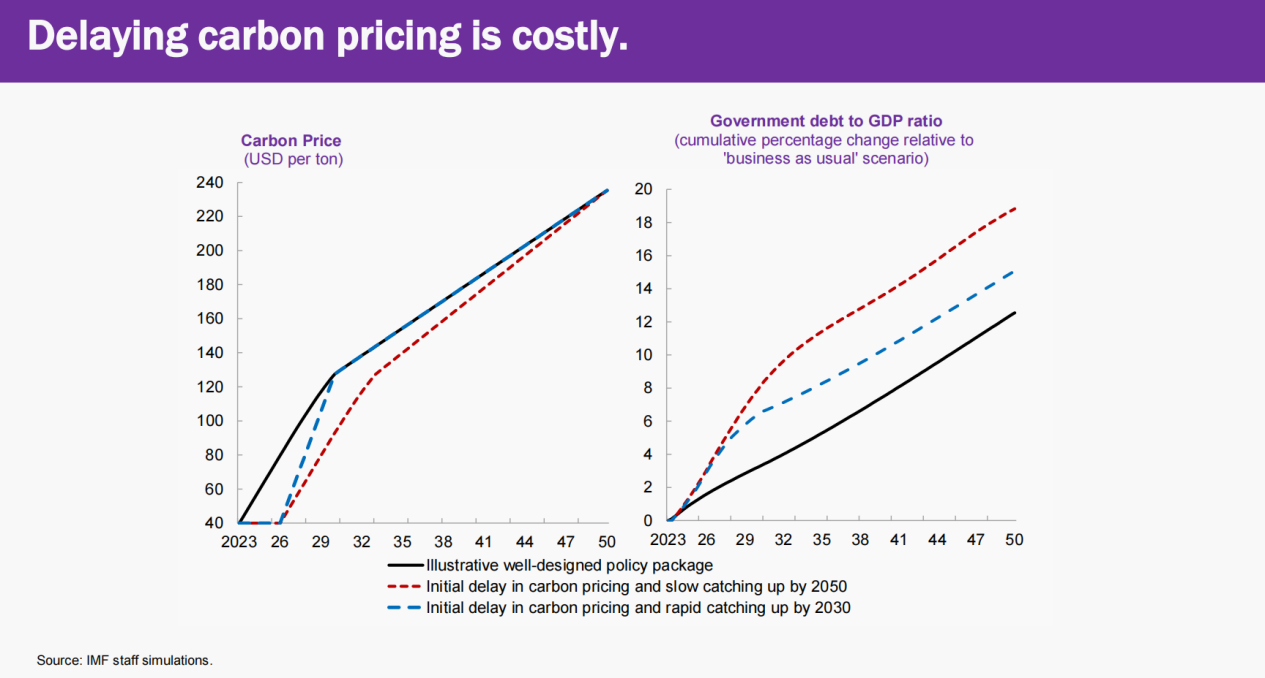

That doesn't mean that some of these actions we could defer it in each case actually delaying some of the carbon price measures even though they are politically not feasible or less accepted.

The monitor will provide you with some analysis also using the same model of a scenario of a three-year delay of the type of currency. So the black line is the baseline of how the carbon prices in the model will behave over time. You can see that advanced countries will rise to about 125 dollars in 2030 and then gradually rise over the long term. If there's a three-year delay, then you will be divided into blue or red dotted lines depending on how the subsequent prices are going to increase over the later years. You could see that the debt increase is even higher. On average, that will increase the debt ratios by about 0.8% to 2% of GDP per year until 2050. So it is important to take action now otherwise the problems only become severe.

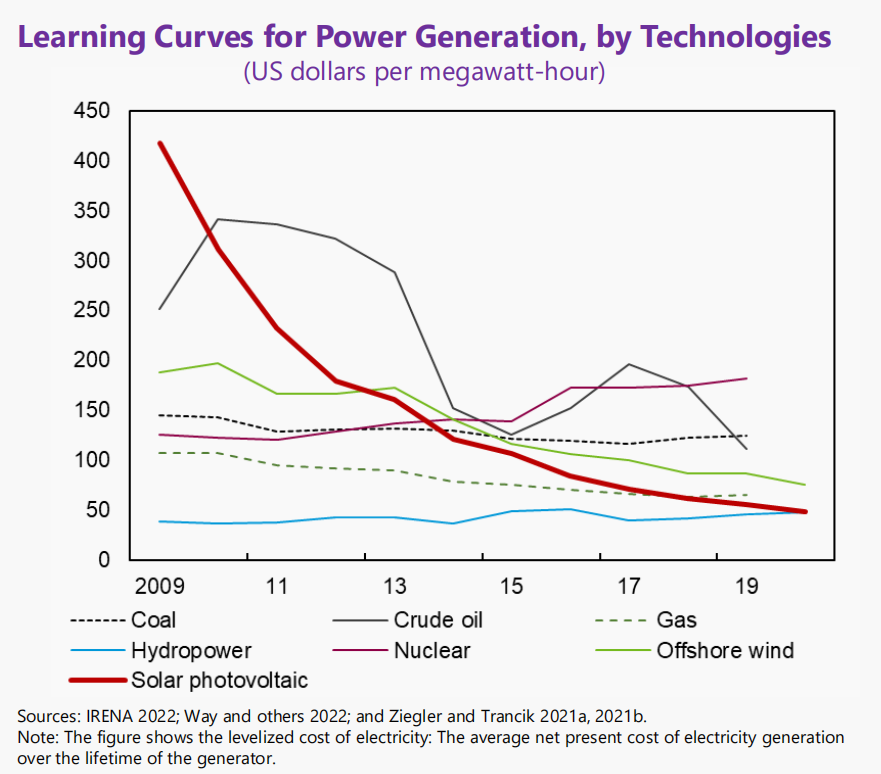

And then there are a good deal of challenges arising in this debt outlook. Certainly, how the impact of the governing actions on time is important, but it depends a lot on what are the type of energy technologies that we use.

Here in the technological sphere, there are both opportunities and challenges. On the good side, I mean, we have seen there's a significant improvement in a lot of renewable resources, including solar energy, hydropower, and wind power. In particular, if you look at solar photovoltaic, which is a red line here, we see a significant reduction in the cost to allow for almost cheaper or even lower than some of the fossil fuels. So there's certainly an adoptable improvement, much better than the projections that we had a decade ago. So this means that a lot of renewable sources of energy are actually now cheaper than fossil fuels, making sure that it's important to use those energies because their cost is actually cheaper.

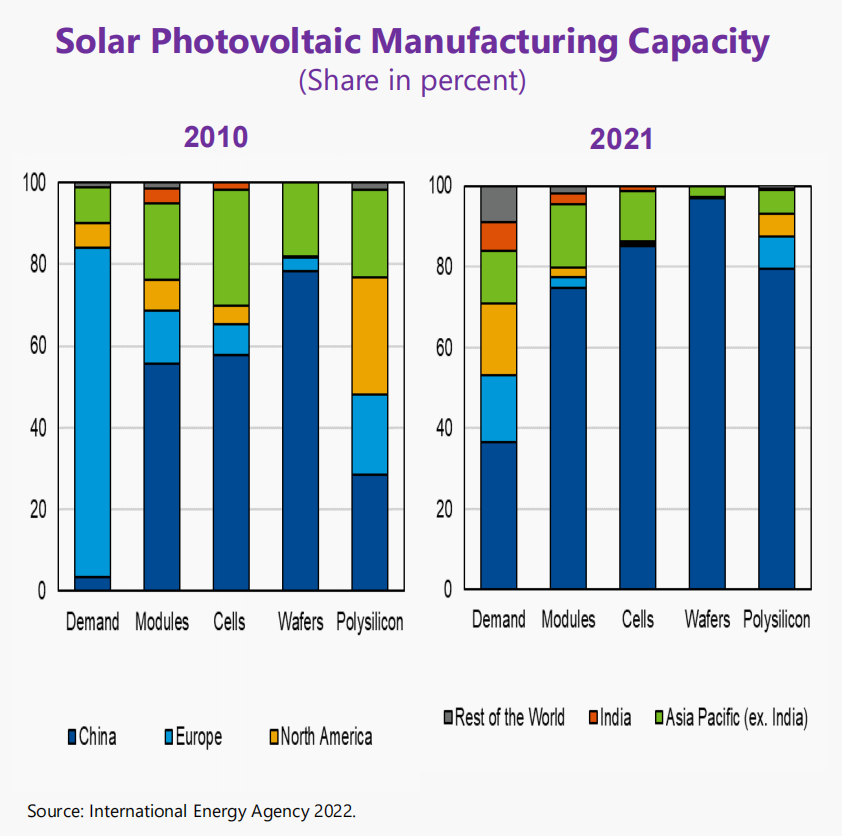

But certainly, there are some challenges. I mean there are a couple of challenges. One is for the demand and supply of renewable sources. And so you could see that from 2010 to 2021, over the last decade, a lot of the demand and supply side area on solar energy is actually concentrated in several countries, including in China. So given the rising geopolitical fragmentation risk, some of the supply chains would provide some of the challenges of our countries adopting these technologies.

At the same time, we have some indirect evidence mentioned in the monitor that is sometimes very difficult for countries to adopt or apply some of these well-known existing technologies, particularly in low-income developing countries. It's very difficult to spread those new technologies to them either because of financing or because of access to that technology. So certainly this will present some challenges. If we could get energy technologies spread quickly to those developing or emerging markets, the cost of the green transition would be lower. But if those technologies remain at the kind of exclusive access to those developing countries, its cost will be higher. This would mean that the green subsidies that are done by a lot of countries may be able to increase low-carbon technology adoption. But this also teaches a lot about whether there's a bottleneck or policies for investment.

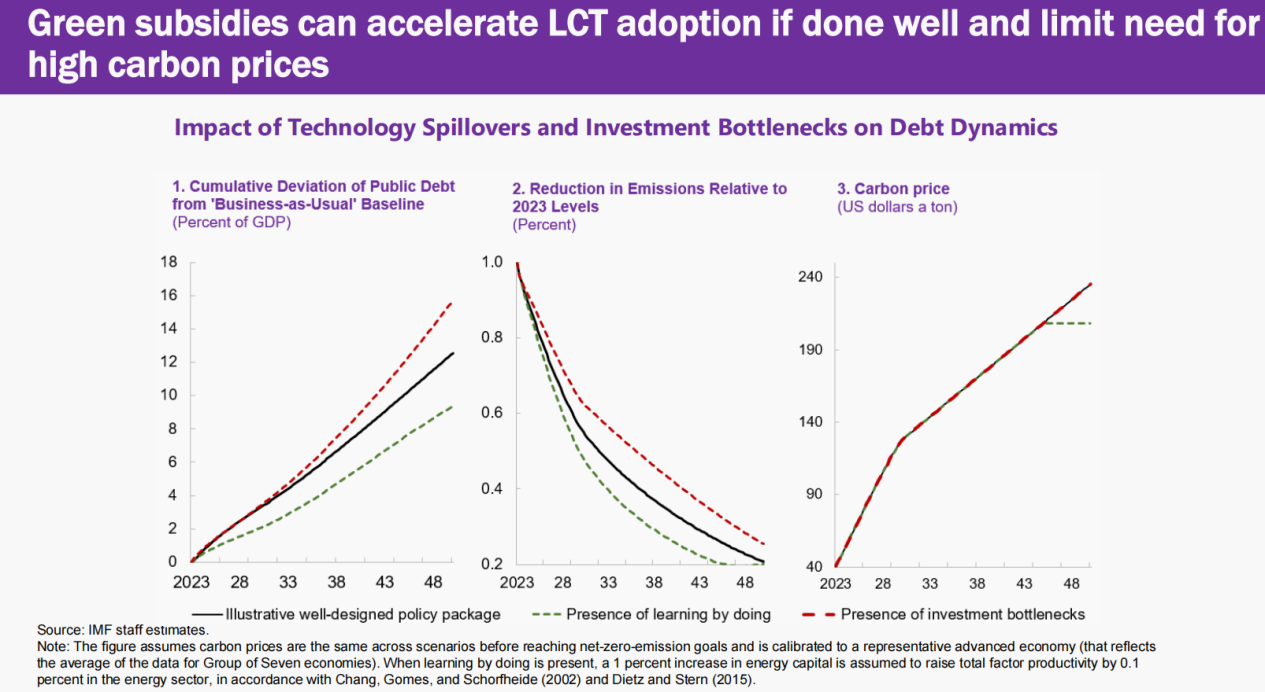

Here we illustrate two scenarios using the same model we talked about before. The Black line is the baseline illustrated showing the increase in public debt on the left side. The reduction in the middle, as well as another line on the carbon price on the right side. So you could see that, if there is a significant improvement in low carbon technology, in the sense that there are not a lot of externalities through other learning by doing or some of the network effects, then one could achieve a faster reduction in emerging emission reduction, which is a green line there, while keeping carbon prices largely the same when it reduces money to reach the maximum of what it should go. This will mean that technology is easier to diffuse and be adopted by countries. And then we could see that the impact of public finances will be more favorable, meaning that you could use fewer fiscal costs in order to reach the same kind of goals without changing carbon prices.

On the other hand, on the negative side, because of the investment bottleneck or investing in these low-carbon technologies, we could see that it would lead to an increase in debt further. And also a slower carbon emission reduction over the years. This was particular in the sense that if there's a large adjustment cost, you will think of standard assets in the fossil fuel sectors, meaning that you cannot just simply close the coal plants or oil fields, but it takes time to do it. At the same time, if you invest in the green sector, it also takes time given the supply chain consideration. So that would only further delay some of the carbon emission schedules, but the cost will be even higher.

3. How can governments facilitate the green transition among firms?

So the last part to think about it as how the government facilitates the transition among firms. This is a pretty big topic and the Fund has already done some analysis in the previous publication, so the Fiscal Monitor this time tends to provide additional features using some of the Microlevel analysis.

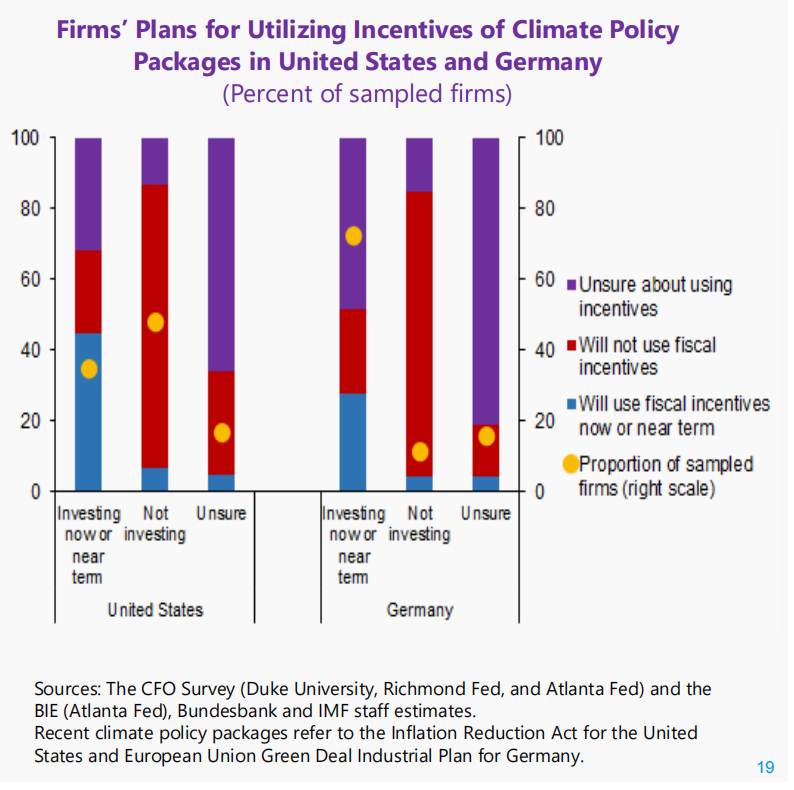

Here we present true results based on the firm platform surveys. Here we are working in partnership with the European Investment Bank in some access to some firm-level surveys which is a representative sample from both Europe as well as United States. At the same time, we also ask countries in partnership with the Federal Reserve Bank as well as the Bundesbank to try to understand how firms respond to the latest government package including the reduction engine in the US as well as the European industrial green policy.

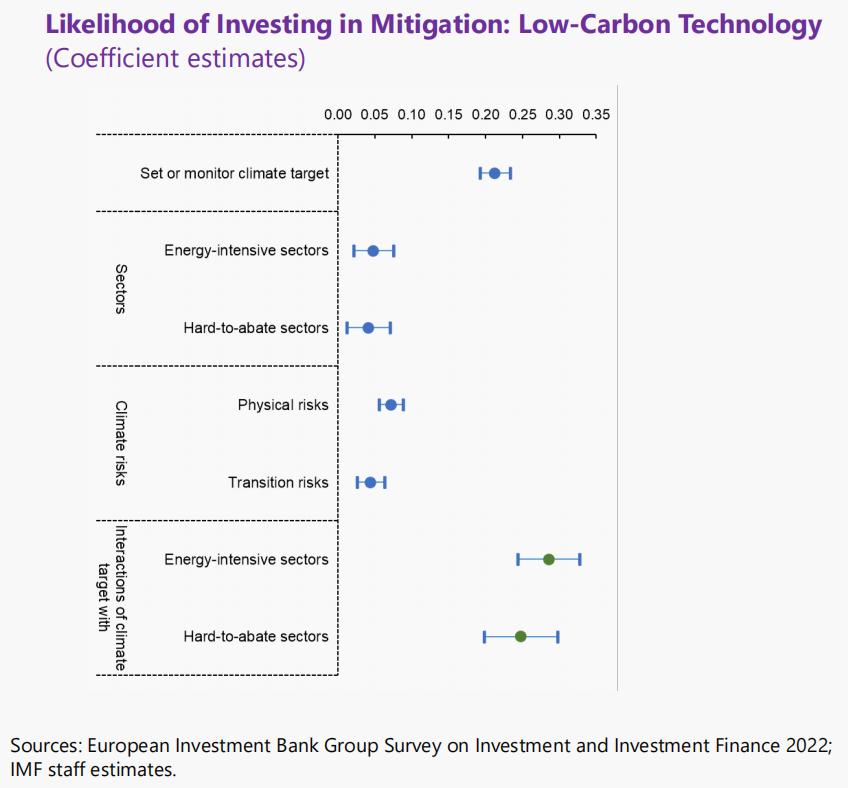

So on the left side, on the EIP data, we see that countries with governments either set or monitor some of the tiny emission goals by firms tend to encourage firms to undertake green investment, meaning that if the government has some regulations in order to set or monitor some of the firm's investment in carbon emissions that actually could help firms to reduce carbon emission. And it has a stronger effect, particularly in those firms that are highly energy-intensive sectors as well as hard-to-abate sectors. These are exactly the areas which we want firms to kind of transition to the green sector. So there's certainly an important role played by the regulations.

On the right side, there's another survey result across firms. Asking them how they behave if the government provided an incentive, a real policy package. And how would they respond? Do they investigate low-carbon technologies? A lot of firms are actually unsure about using those incentives. A lot of firms are in the purple area. But for those who are using them, particularly the German side, many of them have already made some of the efforts in energy efficiency. So it opens up questions about whether the policy package has been allowed by the US or the European Union. It's actually reaching out to the right firms and maybe there are some policy certainty or better targeting could be there.

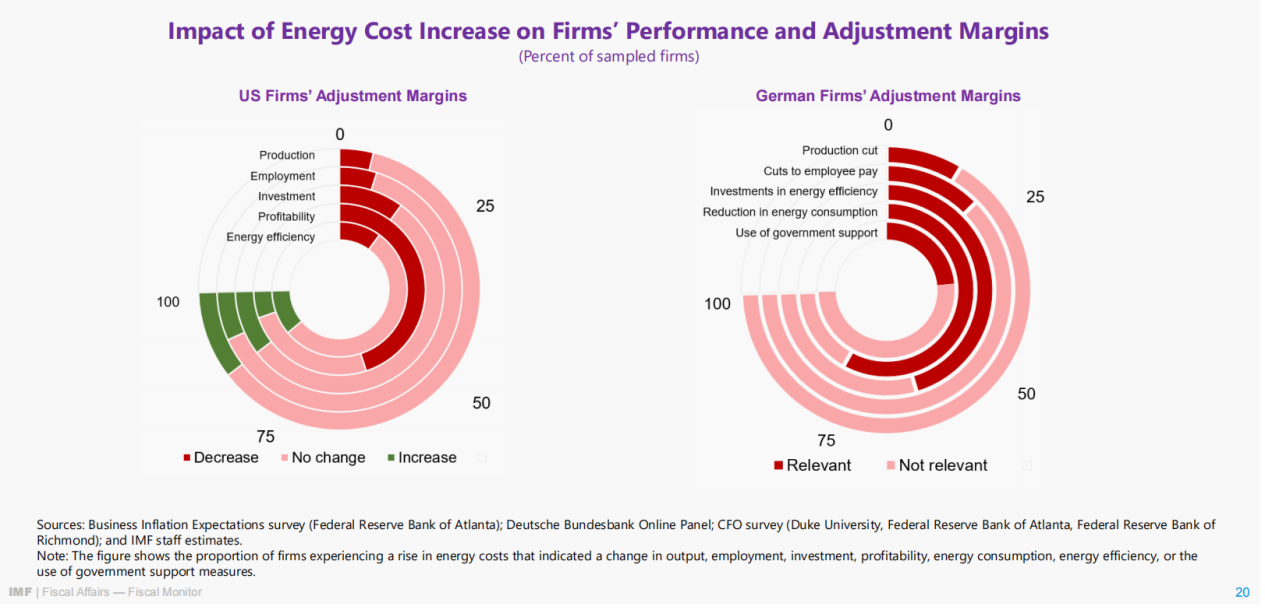

The good news we presented or obtained from this film and for the survey is that films are actually pretty resilient to further changes in the energy crisis. For example, he asked Charles David how they felt over the last year in 2022. How do they respond to the energy shots in the face of the war in Ukraine?

The US Firms' Adjustment Margins are on the left, the German firms are on the right. The US surely has much fewer energy shocks in terms of pricing. So most of them do not see the big impact. Although a lot of them are reporting a reduction in profitability, if you look at the data itself, most of the reductions are clearly small. However, on the German side, the energy shock is much more severe. Maybe, for example, gas prices have increased 5, 7 fold over a very short period. A lot of German firms actually either increase energy efficiency or reduce energy consumption. And they didn't have either production or employment, so those only have a very mild impact. That means that they may be ready to face higher carbon pricing over the coming years without jeopardizing their survival.

Some of the first types of micro-analysis would be very efficient and useful for fiscal market research. Maybe I conclude the presentation on this side. As we have gone through, policymakers face a difficult trilemma. Current climate action is insufficient to achieve a viable path to net zero emissions by the mid-century. Scaling up primarily through spending could put debt sustainability at risk. Raising revenue often crosses political red lines. The Fiscal Monitor is trying to highlight some of these risks as well as provide more viable options. The design schedule is delicate. And it should vary across countries. We have been providing a lot of advice, either in the financial settings or multilateral settings on how to design those packages. The analysis done in the Fiscal Monitor shows that the rise in debt during the green transition will be smaller if policy packages contain robust carbon pricing. Delayed action is costly to help myself as well. The private sector should play a large role in climate actions and financing. here we have a new accompanying chapter in the global financial policy, financial stability report that looks at some of the financing findings. So if you're interested, you can take a look as well. Well-designed green subsidies and appropriate regulatory policies can encourage firms to invest in and adopt LCTs. We should see increasing importance as we move along given that the private sector would play a role. So maybe I'll stop here. Thank you.