Agustín Carstens:Monetary Policy: 10 Years After the Financial Crisis

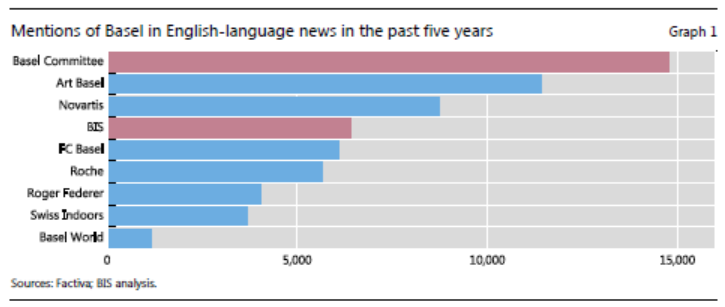

2019-09-10 IMI The BIS is known as the global bank for central banks. Our mission is to promote global monetary and financial stability through international cooperation. We do this in three main ways. First, we conduct economic research and analysis about real-world policy issues facing authorities, focusing on the links between the real economy and the financial system, and taking a long-term and global view. Second, we provide banking services to our 60 member central banks, the wider central banking community and other international institutions. And, third, we act as a forum for discussion and cooperation among policymakers. We host meetings of central bankers in Basel on a continuous basis – the Board gathers every two months – and provide support to a number of standard setters, including the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, the Committee on Payments and Market Infrastructures, and the Financial Stability Board.

By providing a forum for central banks to engage in frank discussions and coordinate policy responses to the crisis, in terms of both monetary policy and financial regulation, the BIS was uniquely placed to observe and assess developments over the years since the Great Financial Crisis. In my remarks today, I will take stock and reflect on where we have come from, to chart where we are going. I will focus mostly on monetary policy, outlining the policy responses and what has been achieved in difficult circumstances. I will then highlight the current challenges and policy implications going forward.

Where did we come from? The crisis and policy responses

Let me start with where we came from. The failure of Lehman Brothers 11 years ago this very month was a critical juncture for the world economy. The ensuing panic and contagion across a wide range of financial markets was worsened by a broad loss of confidence in many types of financial institutions. Credit markets froze and liquidity dried up in critical segments of global financial markets. Without a timely and forceful policy response, we were looking down an economic precipice not seen since the Great Depression. Fortunately, that response came in unprecedented scale, scope and speed.

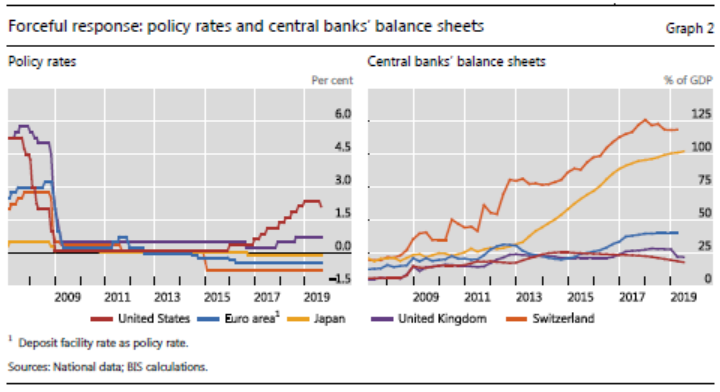

Central banks slashed policy rates, and provided liquidity to support interbank markets, intervening as needed to make sure specific segments of debt and securities markets were working properly. By doing this, central banks were performing their traditional role of lender of last resort. Given the size and complexity of modern financial systems, particularly the reliance on market-based funding, new types of interventions were needed, and on a larger scale than in the past. As a result, central bank balance sheets grew much larger than in normal times (Graph 2).

The BIS is known as the global bank for central banks. Our mission is to promote global monetary and financial stability through international cooperation. We do this in three main ways. First, we conduct economic research and analysis about real-world policy issues facing authorities, focusing on the links between the real economy and the financial system, and taking a long-term and global view. Second, we provide banking services to our 60 member central banks, the wider central banking community and other international institutions. And, third, we act as a forum for discussion and cooperation among policymakers. We host meetings of central bankers in Basel on a continuous basis – the Board gathers every two months – and provide support to a number of standard setters, including the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, the Committee on Payments and Market Infrastructures, and the Financial Stability Board.

By providing a forum for central banks to engage in frank discussions and coordinate policy responses to the crisis, in terms of both monetary policy and financial regulation, the BIS was uniquely placed to observe and assess developments over the years since the Great Financial Crisis. In my remarks today, I will take stock and reflect on where we have come from, to chart where we are going. I will focus mostly on monetary policy, outlining the policy responses and what has been achieved in difficult circumstances. I will then highlight the current challenges and policy implications going forward.

Where did we come from? The crisis and policy responses

Let me start with where we came from. The failure of Lehman Brothers 11 years ago this very month was a critical juncture for the world economy. The ensuing panic and contagion across a wide range of financial markets was worsened by a broad loss of confidence in many types of financial institutions. Credit markets froze and liquidity dried up in critical segments of global financial markets. Without a timely and forceful policy response, we were looking down an economic precipice not seen since the Great Depression. Fortunately, that response came in unprecedented scale, scope and speed.

Central banks slashed policy rates, and provided liquidity to support interbank markets, intervening as needed to make sure specific segments of debt and securities markets were working properly. By doing this, central banks were performing their traditional role of lender of last resort. Given the size and complexity of modern financial systems, particularly the reliance on market-based funding, new types of interventions were needed, and on a larger scale than in the past. As a result, central bank balance sheets grew much larger than in normal times (Graph 2).

Central banks were not alone in their efforts. Large fiscal stimulus packages and far-reaching public guarantees for fragile banking systems gave critical support. The bank guarantees, in particular, were key in preventing default spirals and bank runs. As a result of these actions, the crisis was contained. Even though the major advanced economies experienced the sharpest economic contraction in post-war history, much worse outcomes were avoided and economies were stabilised.

Since then, monetary policy and financial regulation reforms have worked in tandem to lay the foundations for a sustained recovery. Aggregate demand was supported by continued monetary accommodation, through low and in some cases even negative interest rates, as well as a broad set of unconventional monetary measures. I’ll come back to these shortly. At the same time, decisive regulatory and supervisory action promoted financial resilience. In particular, the Basel Committee agreed on comprehensive and wide-ranging reforms for internationally active banks, in the form of Basel III. These reforms went a long way in addressing the main fault lines that the Great Financial Crisis exposed in the banking system, including excess leverage, inadequate loss-absorbing capital and over-exposure to liquidity risk.

Central banks have learned a lot over the past decade about potential new ways of implementing monetary policy. The use of unconventional monetary policy tools was largely born out of necessity: partly to address disruptions in monetary policy transmission and partly to provide additional monetary stimulus once policy rates were constrained by the effective lower bound. Broadly speaking, these unconventional monetary policy tools can be divided into four types of measures: lending operations, asset purchase programmes, forward guidance and negative interest rate policies. Let me say a few words about each of them.

Lending operations were used early in the crisis to support market functioning. To make sure that liquidity was available to everyone who needed it, central banks expanded both the types of assets they accepted as eligible collateral for loans and the set of counterparties they lent to. In addition, to foster market confidence about the future availability of liquidity, loans were extended over longer periods. On the whole, these lending operations helped ease liquidity strains, restore the monetary transmission channels and alleviate pressures in bank funding markets. In doing so, they supported credit flows to firms and households. That said, there were some inefficiencies in the allocation of credit and concerns about potential disintermediation of some financial market segments.

Asset purchase programmes played an important role in central banks’ interventions. They aimed mainly to ease broad financial conditions by supporting asset valuations. The interventions covered a wide range of market segments, depending on the nature of disruption and the importance of the relevant asset class for monetary transmission. Most prominent were purchases of government bonds aimed at lowering long-term yields, although many programmes also focused on private securities. Asset purchases were generally very effective in lowering risk premia and easing market conditions. The large purchases of government securities did lead to concerns about safe asset scarcity and bond market functioning. But the introduction of securities lending programmes largely alleviated them. More significant side effects came in the form of financial spillovers to other countries as low yields in the major economies pushed investors to seek higher returns globally.

Central banks also used forward guidance to clarify their intentions regarding future policy settings and to communicate their commitment to pursue their mandates. Promising to keep rates at a certain level was crucial at times of heightened uncertainty about the economic outlook. Forward guidance also helped bring different unconventional monetary policy tools together into an overall package, making policymakers’ strategic intentions clearer. Overall, forward guidance was quite effective in shifting down and flattening expected policy paths, as well as reducing uncertainty. On the flip side, a key challenge has been to make clear that forward guidance partly depends on the economy’s evolution, to avoid misinterpretation, which could generate unwelcome market reactions.

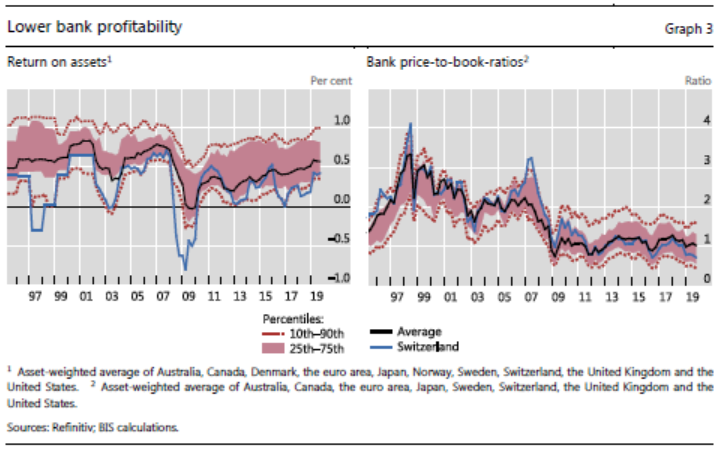

Finally, negative interest rate policies were implemented by a number of central banks to overcome the zero lower bound on interest rates. Reducing policy rates below zero can stimulate the economy by supporting credit and demand as long as they transmit to market rates. Recent experience has shown that borrowing and lending rates did decline, providing the desired expansionary stimulus. But concerns about negative customer reaction have prevented banks from lowering the return on deposits of households and small firms below zero. And that has also meant that, over time, such low rates can depress banks’ net interest margins and their ability to build up capital – the foundation for sustainable lending. Low bank valuations reflect this profitability challenge (Graph 3).

Central banks were not alone in their efforts. Large fiscal stimulus packages and far-reaching public guarantees for fragile banking systems gave critical support. The bank guarantees, in particular, were key in preventing default spirals and bank runs. As a result of these actions, the crisis was contained. Even though the major advanced economies experienced the sharpest economic contraction in post-war history, much worse outcomes were avoided and economies were stabilised.

Since then, monetary policy and financial regulation reforms have worked in tandem to lay the foundations for a sustained recovery. Aggregate demand was supported by continued monetary accommodation, through low and in some cases even negative interest rates, as well as a broad set of unconventional monetary measures. I’ll come back to these shortly. At the same time, decisive regulatory and supervisory action promoted financial resilience. In particular, the Basel Committee agreed on comprehensive and wide-ranging reforms for internationally active banks, in the form of Basel III. These reforms went a long way in addressing the main fault lines that the Great Financial Crisis exposed in the banking system, including excess leverage, inadequate loss-absorbing capital and over-exposure to liquidity risk.

Central banks have learned a lot over the past decade about potential new ways of implementing monetary policy. The use of unconventional monetary policy tools was largely born out of necessity: partly to address disruptions in monetary policy transmission and partly to provide additional monetary stimulus once policy rates were constrained by the effective lower bound. Broadly speaking, these unconventional monetary policy tools can be divided into four types of measures: lending operations, asset purchase programmes, forward guidance and negative interest rate policies. Let me say a few words about each of them.

Lending operations were used early in the crisis to support market functioning. To make sure that liquidity was available to everyone who needed it, central banks expanded both the types of assets they accepted as eligible collateral for loans and the set of counterparties they lent to. In addition, to foster market confidence about the future availability of liquidity, loans were extended over longer periods. On the whole, these lending operations helped ease liquidity strains, restore the monetary transmission channels and alleviate pressures in bank funding markets. In doing so, they supported credit flows to firms and households. That said, there were some inefficiencies in the allocation of credit and concerns about potential disintermediation of some financial market segments.

Asset purchase programmes played an important role in central banks’ interventions. They aimed mainly to ease broad financial conditions by supporting asset valuations. The interventions covered a wide range of market segments, depending on the nature of disruption and the importance of the relevant asset class for monetary transmission. Most prominent were purchases of government bonds aimed at lowering long-term yields, although many programmes also focused on private securities. Asset purchases were generally very effective in lowering risk premia and easing market conditions. The large purchases of government securities did lead to concerns about safe asset scarcity and bond market functioning. But the introduction of securities lending programmes largely alleviated them. More significant side effects came in the form of financial spillovers to other countries as low yields in the major economies pushed investors to seek higher returns globally.

Central banks also used forward guidance to clarify their intentions regarding future policy settings and to communicate their commitment to pursue their mandates. Promising to keep rates at a certain level was crucial at times of heightened uncertainty about the economic outlook. Forward guidance also helped bring different unconventional monetary policy tools together into an overall package, making policymakers’ strategic intentions clearer. Overall, forward guidance was quite effective in shifting down and flattening expected policy paths, as well as reducing uncertainty. On the flip side, a key challenge has been to make clear that forward guidance partly depends on the economy’s evolution, to avoid misinterpretation, which could generate unwelcome market reactions.

Finally, negative interest rate policies were implemented by a number of central banks to overcome the zero lower bound on interest rates. Reducing policy rates below zero can stimulate the economy by supporting credit and demand as long as they transmit to market rates. Recent experience has shown that borrowing and lending rates did decline, providing the desired expansionary stimulus. But concerns about negative customer reaction have prevented banks from lowering the return on deposits of households and small firms below zero. And that has also meant that, over time, such low rates can depress banks’ net interest margins and their ability to build up capital – the foundation for sustainable lending. Low bank valuations reflect this profitability challenge (Graph 3).

Finally, negative interest rate policies were implemented by a number of central banks to overcome the zero lower bound on interest rates. Reducing policy rates below zero can stimulate the economy by supporting credit and demand as long as they transmit to market rates. Recent experience has shown that borrowing and lending rates did decline, providing the desired expansionary stimulus. But concerns about negative customer reaction have prevented banks from lowering the return on deposits of households and small firms below zero. And that has also meant that, over time, such low rates can depress banks’ net interest margins and their ability to build up capital – the foundation for sustainable lending. Low bank valuations reflect this profitability challenge (Graph 3).

Finally, negative interest rate policies were implemented by a number of central banks to overcome the zero lower bound on interest rates. Reducing policy rates below zero can stimulate the economy by supporting credit and demand as long as they transmit to market rates. Recent experience has shown that borrowing and lending rates did decline, providing the desired expansionary stimulus. But concerns about negative customer reaction have prevented banks from lowering the return on deposits of households and small firms below zero. And that has also meant that, over time, such low rates can depress banks’ net interest margins and their ability to build up capital – the foundation for sustainable lending. Low bank valuations reflect this profitability challenge (Graph 3).

While all these unconventional monetary policy tools do have inevitable side effects, the overall consensus is that they helped central banks address the very difficult circumstances they faced at a time when conventional policy was not enough. The responsiveness of financial conditions to these policies first stabilised and then stimulated the economy. This supported market sentiment and staved off deflation risks. As such, these unconventional tools are valuable additions to central banks’ toolbox. It is important to note that they are much more effective when they are deployed in conjunction with appropriate supervisory, prudential and fiscal policies, and as part of a broader policy framework that avoids unnecessary burdens on the central bank. I will return to this point later.

Where do we stand today? Outcome and challenges ahead

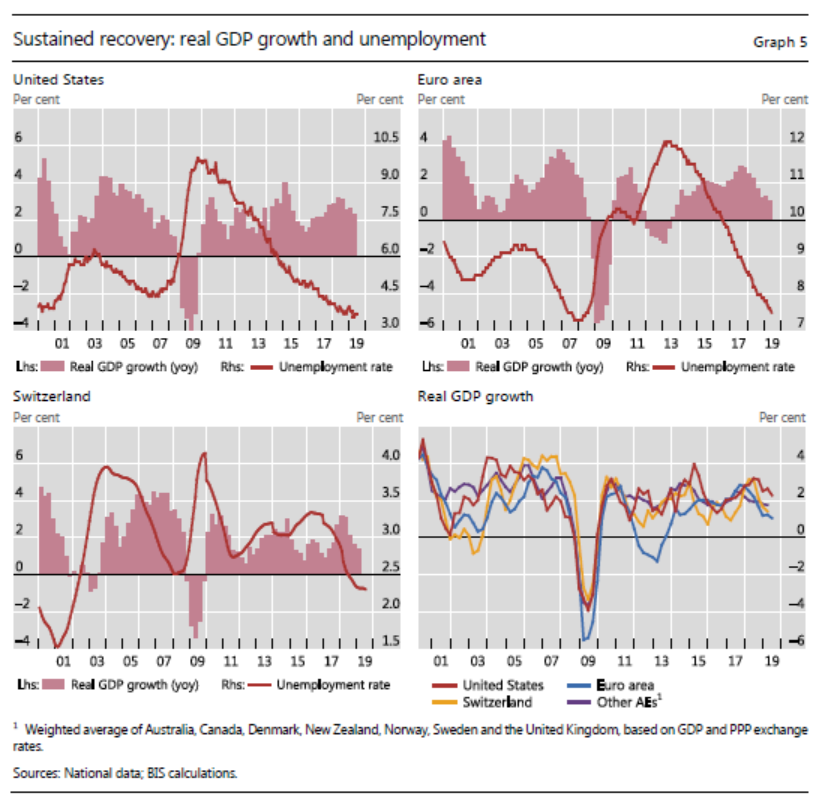

So where do we stand today, 10 years after the crisis? In many key respects, we have come a long way. In the major economies that bore the brunt of the crisis, economic growth has been restored, unemployment rates have been drastically reduced and the banking system’s safety buffers have been greatly strengthened (Graph 5). The United States, which was the epicentre of the crisis, has now enjoyed its longest economic expansion in history, and its unemployment rate is the lowest in 50 years, with around 20 million jobs created over the last 10 years. In the euro area, growth has also recovered, although at a slower pace, and unemployment rates have steadily declined to pre-crisis levels. The picture is similar in Switzerland and across other major economies. At the same time, the banking system has been repaired and its resilience significantly strengthened. Capital ratios for most institutions are now much higher than before the crisis and above regulatory requirements. None of this could have been achieved without central banks’ forceful actions.

While all these unconventional monetary policy tools do have inevitable side effects, the overall consensus is that they helped central banks address the very difficult circumstances they faced at a time when conventional policy was not enough. The responsiveness of financial conditions to these policies first stabilised and then stimulated the economy. This supported market sentiment and staved off deflation risks. As such, these unconventional tools are valuable additions to central banks’ toolbox. It is important to note that they are much more effective when they are deployed in conjunction with appropriate supervisory, prudential and fiscal policies, and as part of a broader policy framework that avoids unnecessary burdens on the central bank. I will return to this point later.

Where do we stand today? Outcome and challenges ahead

So where do we stand today, 10 years after the crisis? In many key respects, we have come a long way. In the major economies that bore the brunt of the crisis, economic growth has been restored, unemployment rates have been drastically reduced and the banking system’s safety buffers have been greatly strengthened (Graph 5). The United States, which was the epicentre of the crisis, has now enjoyed its longest economic expansion in history, and its unemployment rate is the lowest in 50 years, with around 20 million jobs created over the last 10 years. In the euro area, growth has also recovered, although at a slower pace, and unemployment rates have steadily declined to pre-crisis levels. The picture is similar in Switzerland and across other major economies. At the same time, the banking system has been repaired and its resilience significantly strengthened. Capital ratios for most institutions are now much higher than before the crisis and above regulatory requirements. None of this could have been achieved without central banks’ forceful actions.

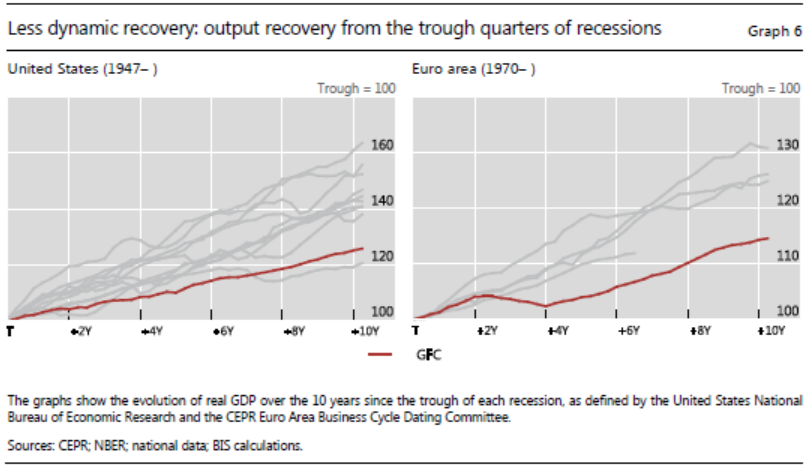

That said, this economic recovery has been less dynamic than previous rebounds (Graph 6). This is partly due to the scars left by the financial crisis, including the need to work off debt overhangs and reallocate resources from overextended sectors to more productive ones. This took time and underscores the lasting damage that financial crises can leave on the economy. Reducing their likelihood and potential costs remains a priority.

That said, this economic recovery has been less dynamic than previous rebounds (Graph 6). This is partly due to the scars left by the financial crisis, including the need to work off debt overhangs and reallocate resources from overextended sectors to more productive ones. This took time and underscores the lasting damage that financial crises can leave on the economy. Reducing their likelihood and potential costs remains a priority.

For monetary policy, navigating the current juncture is a difficult balancing act. Let me highlight four challenges in particular.

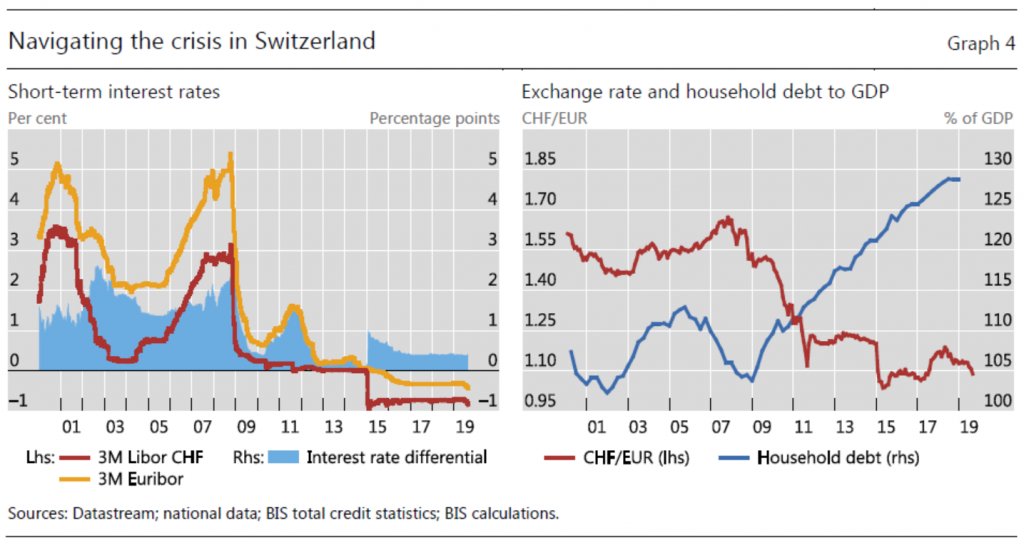

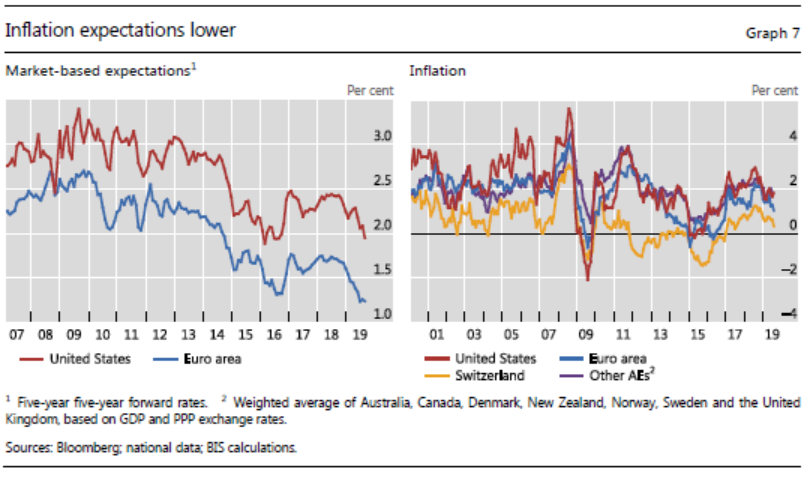

The first has to do with low inflation. Throughout the decade since the crisis, inflation has been remarkably subdued. On the one hand, we have been fortunate that outright destabilising deflation was avoided and that prices have been stable overall. Indeed, in Switzerland output growth has been solid against a backdrop of low and sometimes negative inflation. On the other hand, persistent undershooting of inflation targets and the greater likelihood of hitting the lower bound on policy rates in the future pose risks to the de-anchoring of inflation expectations (Graph 7).

For monetary policy, navigating the current juncture is a difficult balancing act. Let me highlight four challenges in particular.

The first has to do with low inflation. Throughout the decade since the crisis, inflation has been remarkably subdued. On the one hand, we have been fortunate that outright destabilising deflation was avoided and that prices have been stable overall. Indeed, in Switzerland output growth has been solid against a backdrop of low and sometimes negative inflation. On the other hand, persistent undershooting of inflation targets and the greater likelihood of hitting the lower bound on policy rates in the future pose risks to the de-anchoring of inflation expectations (Graph 7).

Not only has inflation been persistently low in many countries, but its relationship with key economic variables, notably output, has changed. Part of the reason for this lies in structural changes – including globalisation, digitalisation and the wage bargaining process – that have made inflation less responsive to domestic demand pressures. This has made it harder for central banks to steer inflation, at least in the short run and when overall price changes are small.

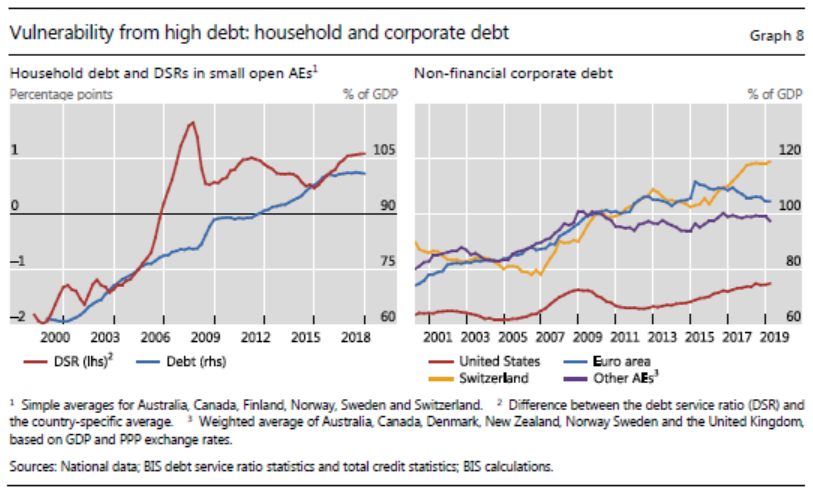

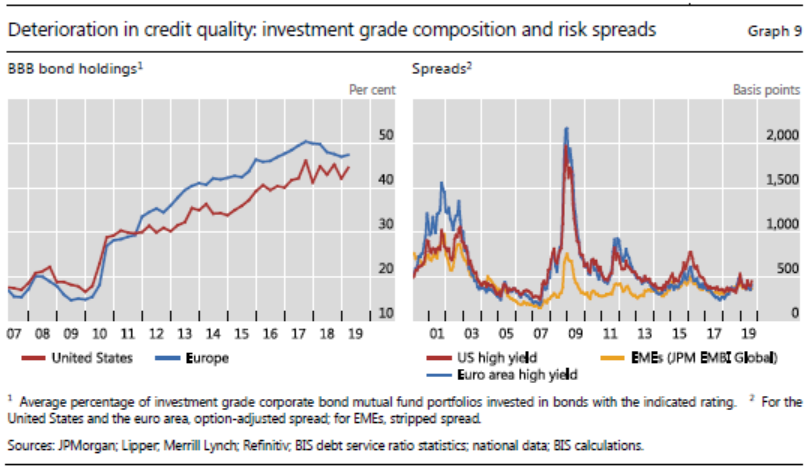

The second challenge is that high debt levels and the search for yield have left economies vulnerable to negative shocks (Graph 8). Countries that were not at the epicentre of the crisis, particularly small open economies like Australia, Canada, the Nordic countries and Switzerland, have seen sustained increases in household debt. Moreover, debt service ratios have increased even as interest rates have fallen. Corporate debt has also expanded significantly. Global non-financial corporate debt, including bonds and loans, has more than doubled over the past decade. There is also evidence of declining credit standards. In advanced economies, the share of bonds with the lowest investment grade rating in portfolios of mutual funds that hold investment grade corporate bonds has doubled to just under 50% in both the US and Europe. Credit spreads are also relatively compressed (Graph 9). The leveraged loan market has expanded rapidly and is now some $3 trillion in size. Structured products like collateralised loan obligations have surged, posing risks that could be amplified through the financial system if credit conditions deteriorate abruptly.

Not only has inflation been persistently low in many countries, but its relationship with key economic variables, notably output, has changed. Part of the reason for this lies in structural changes – including globalisation, digitalisation and the wage bargaining process – that have made inflation less responsive to domestic demand pressures. This has made it harder for central banks to steer inflation, at least in the short run and when overall price changes are small.

The second challenge is that high debt levels and the search for yield have left economies vulnerable to negative shocks (Graph 8). Countries that were not at the epicentre of the crisis, particularly small open economies like Australia, Canada, the Nordic countries and Switzerland, have seen sustained increases in household debt. Moreover, debt service ratios have increased even as interest rates have fallen. Corporate debt has also expanded significantly. Global non-financial corporate debt, including bonds and loans, has more than doubled over the past decade. There is also evidence of declining credit standards. In advanced economies, the share of bonds with the lowest investment grade rating in portfolios of mutual funds that hold investment grade corporate bonds has doubled to just under 50% in both the US and Europe. Credit spreads are also relatively compressed (Graph 9). The leveraged loan market has expanded rapidly and is now some $3 trillion in size. Structured products like collateralised loan obligations have surged, posing risks that could be amplified through the financial system if credit conditions deteriorate abruptly.

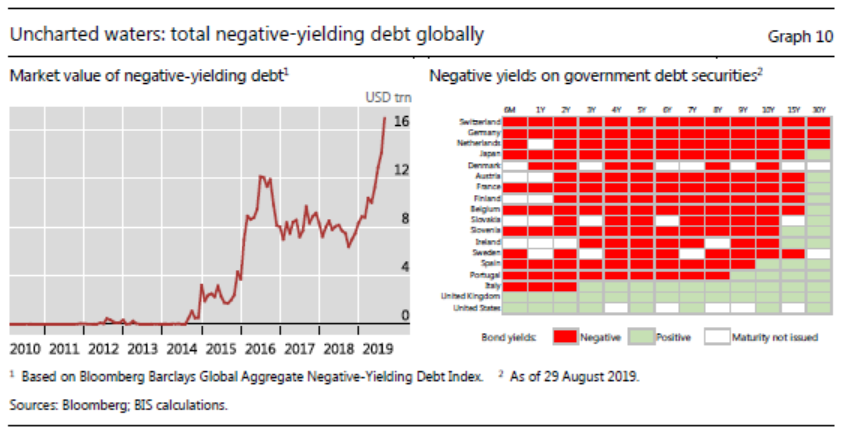

The third challenge central banks now face is that of limited policy room. Interest rates, both short and long, are at historical lows in many countries. And the size of central bank balance sheets remains unprecedented. A key question is whether and to what extent unconventional monetary policy can be applied to provide additional stimulus if needed. Negative interest rates, in particular, are a prominent issue. So far, modestly negative rates have not led to major disruptions in market functioning. But with some $16 trillion of bonds now trading at negative yields – that’s roughly a quarter of the global bond market, including government and corporate debt – the question is how much more rates can be pushed into negative territory, and whether the side effects outweigh the benefits (Graph 10). We have seen some of you here introducing negative rates on deposits exceeding large amounts, while negative mortgage rates have become a reality in Denmark. We have little experience with such situations, and so have to proceed cautiously and be mindful of potential side effects if these conditions persist.

The third challenge central banks now face is that of limited policy room. Interest rates, both short and long, are at historical lows in many countries. And the size of central bank balance sheets remains unprecedented. A key question is whether and to what extent unconventional monetary policy can be applied to provide additional stimulus if needed. Negative interest rates, in particular, are a prominent issue. So far, modestly negative rates have not led to major disruptions in market functioning. But with some $16 trillion of bonds now trading at negative yields – that’s roughly a quarter of the global bond market, including government and corporate debt – the question is how much more rates can be pushed into negative territory, and whether the side effects outweigh the benefits (Graph 10). We have seen some of you here introducing negative rates on deposits exceeding large amounts, while negative mortgage rates have become a reality in Denmark. We have little experience with such situations, and so have to proceed cautiously and be mindful of potential side effects if these conditions persist.

Last, but definitely not least, is the current economic outlook. Apart from the high corporate debt that I mentioned before, weak bank profits in advanced economies and deleveraging in some major emerging market economies all pose a risk to the outlook. But at the top of the list is the uncertainty stemming from the return of protectionism and the resulting trade tensions. Trade wars have no winners, only losers. And the losers are not only consumers and companies in the countries engaged in the trade war, but also consumers and companies in the trading partners of those countries, and the trading partners of those trading partners. The ripples from a trade war spread very quickly.

Where do we go from here? Policy options

So that’s where we stand today. The economic recovery has been sustained, and we are in much better shape today than 10 years ago. Central banks have done all that they could have – more than many could have imagined. Faced with a very challenging and fluid set of circumstances, monetary policy responded forcefully to ward off downside risks and keep the recovery on an even keel. And central banks have achieved this despite binding constraints on their instruments.

But monetary policy cannot overturn structural forces buffeting the economy. As vulnerabilities have developed again and growth momentum has become increasingly exposed to downside risks, monetary policy cannot be expected to single-handedly sustain growth as it has over the past decade. Running monetary policy close to its limits for too long increases the risks from adverse side effects, not least in the form of accumulating financial imbalances that could weigh on macroeconomic performance in the future. Monetary policy can act as a backstop for growth. But other engines and policy levers will need to contribute. And from a long-run perspective, no engine is stronger or more durable than structural reforms.

Labour and product market reforms need to be pushed through to reinvigorate economic dynamism and reap the full benefits that new technologies offer. Efficient resource allocation – moving capital and labour from low-productivity firms and sectors to more productive ones – underpins the process of “creative destruction” that is vital for long-run growth. Declines in measures of firm creation and destruction, a proxy for the process of resource allocation, is a worrying sign in this respect. So too is the growth of so-called “zombie firms”, firms whose profits cannot cover interest payments on debt.

On the financial front, Basel III is a milestone achievement. But its full benefits will only be realised if the reforms are implemented in a timely and consistent way. This will give stakeholders clarity and certainty, and reduce risks of regulatory fragmentation and cross-border competitive distortions.

In terms of other policy levers, fiscal policy can be a powerful tool to keep growth balanced. Provided that fiscal space is available, well targeted fiscal measures not only provide short-term stimulus, but also create incentives that support growth in the medium term, particularly if they boost innovation.

And in the face of growing vulnerabilities, it will be increasingly important to use macroprudential tools judiciously to mitigate risks in specific sectors of the financial system. The experience in many countries has shown how useful such measures have been for housing markets. And provided there is good coordination, macroprudential tools can be a powerful complement to monetary policy.

Finally, it goes without saying that maintaining the open global trade system that has fostered tremendous gains is of paramount importance.

Let me end by repeating the central message of this year’s BIS Annual Economic Report: monetary policy cannot bear all the burden of sustainable growth. It’s time to ignite all policy engines. Thank you for your attention.

Last, but definitely not least, is the current economic outlook. Apart from the high corporate debt that I mentioned before, weak bank profits in advanced economies and deleveraging in some major emerging market economies all pose a risk to the outlook. But at the top of the list is the uncertainty stemming from the return of protectionism and the resulting trade tensions. Trade wars have no winners, only losers. And the losers are not only consumers and companies in the countries engaged in the trade war, but also consumers and companies in the trading partners of those countries, and the trading partners of those trading partners. The ripples from a trade war spread very quickly.

Where do we go from here? Policy options

So that’s where we stand today. The economic recovery has been sustained, and we are in much better shape today than 10 years ago. Central banks have done all that they could have – more than many could have imagined. Faced with a very challenging and fluid set of circumstances, monetary policy responded forcefully to ward off downside risks and keep the recovery on an even keel. And central banks have achieved this despite binding constraints on their instruments.

But monetary policy cannot overturn structural forces buffeting the economy. As vulnerabilities have developed again and growth momentum has become increasingly exposed to downside risks, monetary policy cannot be expected to single-handedly sustain growth as it has over the past decade. Running monetary policy close to its limits for too long increases the risks from adverse side effects, not least in the form of accumulating financial imbalances that could weigh on macroeconomic performance in the future. Monetary policy can act as a backstop for growth. But other engines and policy levers will need to contribute. And from a long-run perspective, no engine is stronger or more durable than structural reforms.

Labour and product market reforms need to be pushed through to reinvigorate economic dynamism and reap the full benefits that new technologies offer. Efficient resource allocation – moving capital and labour from low-productivity firms and sectors to more productive ones – underpins the process of “creative destruction” that is vital for long-run growth. Declines in measures of firm creation and destruction, a proxy for the process of resource allocation, is a worrying sign in this respect. So too is the growth of so-called “zombie firms”, firms whose profits cannot cover interest payments on debt.

On the financial front, Basel III is a milestone achievement. But its full benefits will only be realised if the reforms are implemented in a timely and consistent way. This will give stakeholders clarity and certainty, and reduce risks of regulatory fragmentation and cross-border competitive distortions.

In terms of other policy levers, fiscal policy can be a powerful tool to keep growth balanced. Provided that fiscal space is available, well targeted fiscal measures not only provide short-term stimulus, but also create incentives that support growth in the medium term, particularly if they boost innovation.

And in the face of growing vulnerabilities, it will be increasingly important to use macroprudential tools judiciously to mitigate risks in specific sectors of the financial system. The experience in many countries has shown how useful such measures have been for housing markets. And provided there is good coordination, macroprudential tools can be a powerful complement to monetary policy.

Finally, it goes without saying that maintaining the open global trade system that has fostered tremendous gains is of paramount importance.

Let me end by repeating the central message of this year’s BIS Annual Economic Report: monetary policy cannot bear all the burden of sustainable growth. It’s time to ignite all policy engines. Thank you for your attention.