David Marsh: Speedy Communication Needed——Tough Reinvestment Choices Amid 'Unfairness' Fears

2018-11-06 IMI As a result, far more redemptions will need to be reinvested in German bonds than the strict capital key suggests.

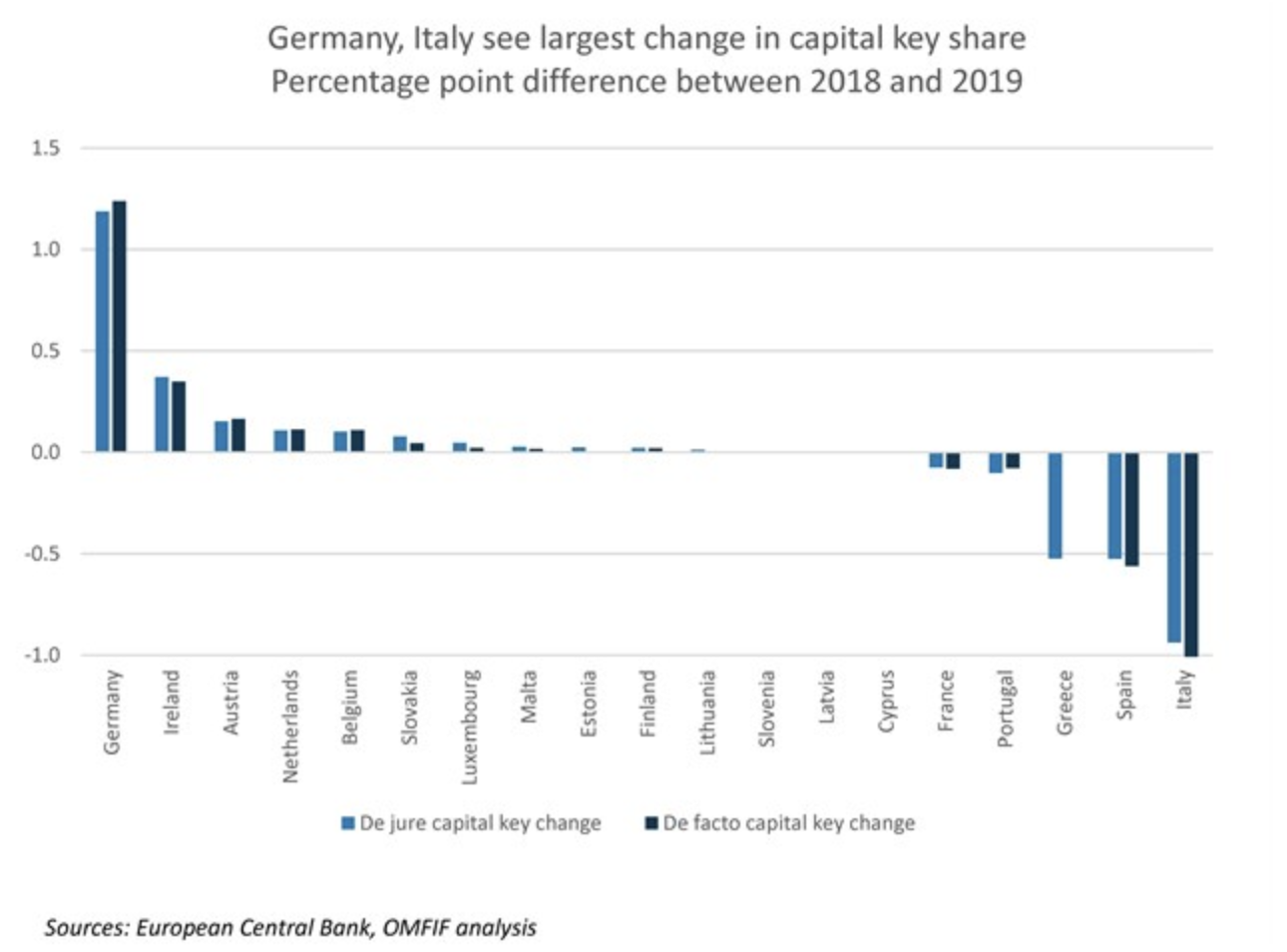

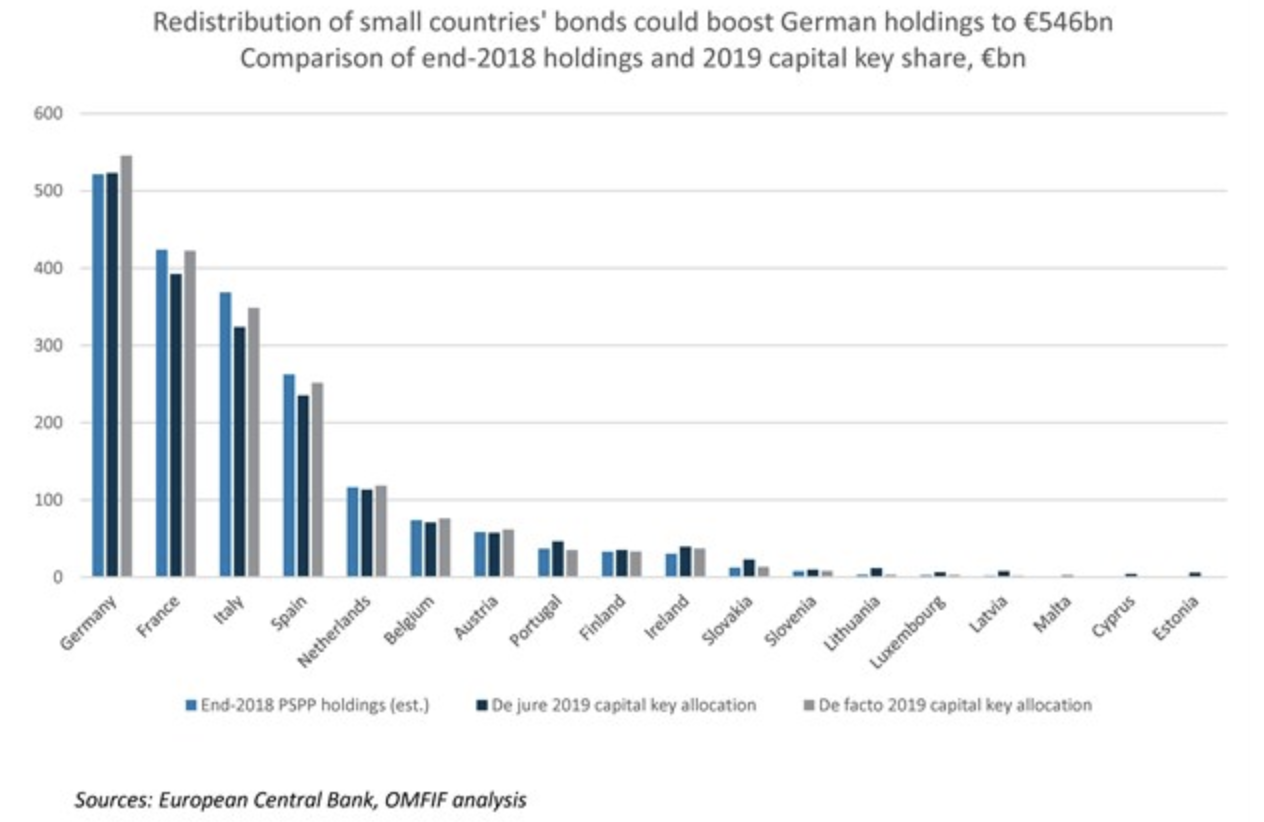

The actual, 'de facto' share of German public sector bonds bought so far is 26.7%, some 1.1 percentage points above its strict capital key share. Factoring in the recalibration of the capital key, Germany's de facto share will rise to 27.9%. This suggests more than €24.2bn worth of additional reinvestment in German bonds will have to be made after December 2018 to ensure the stock of its bonds matches this de facto capital key share. That compares with just €1.6bn of reinvestment according to the strict capital key share.

Whether the ECB can find enough German bonds in which to reinvest to fulfil this allocation is an important consideration. By the end of December, almost €522bn of German bonds will have been purchased. This is starting to push up against the ECB's restriction on purchases of more than 33% of any issuer's outstanding bonds.

As a result, far more redemptions will need to be reinvested in German bonds than the strict capital key suggests.

The actual, 'de facto' share of German public sector bonds bought so far is 26.7%, some 1.1 percentage points above its strict capital key share. Factoring in the recalibration of the capital key, Germany's de facto share will rise to 27.9%. This suggests more than €24.2bn worth of additional reinvestment in German bonds will have to be made after December 2018 to ensure the stock of its bonds matches this de facto capital key share. That compares with just €1.6bn of reinvestment according to the strict capital key share.

Whether the ECB can find enough German bonds in which to reinvest to fulfil this allocation is an important consideration. By the end of December, almost €522bn of German bonds will have been purchased. This is starting to push up against the ECB's restriction on purchases of more than 33% of any issuer's outstanding bonds.

Additional purchases via reinvesting redemptions of other countries' maturing bonds will add to the strain. The ECB has not yet decided – let alone announced – how it will conduct reinvestments. The governing council may yet decide to increase the issuer limit to avoid this constraint. However, this is likely to meet political resistance.

A more positive effect of the 'de facto' capital key deviation reflects the position in Italy. The required drop in ECB holdings of Italian bonds will be lower than it would be using the de jure capital key allocation.

Italian bonds will have been overpurchased by more than €26bn by end-2018 according to the country's strict capital key share. To match Italy's reduced 2019 capital key, the Banca d'Italia would have to reduce its holdings of Italian debt by almost €45bn. However, the need to make up for under-purchases in countries with smaller bond markets means that this figure is closer to €21bn.

While still a large reduction for a country planning to expand debt issuance in the next budget, the impact will be less severe than it might otherwise be.

Italy may complain that its capital key share will fall to 16.6% from 17.5% next year. Yet the actual share of its bonds that will be purchased in the ECB's reinvestment is likely to be closer to 17.8% – larger than its current de jure figure, but smaller than its current de facto share of 18.8%.

Many other technical issues need to be clarified, for example on changing the maturities of reinvested bonds.

Replacing maturing Italian debt with longer-dated securities would help flatten the yield curve and be more stimulative than reinvesting in bonds with a similar maturity profile. This could strengthen the capital position of Italian banks, which own large shares of Italian government debt, and which should benefit from rising prices.

Theoretically such flexibility would also allow German reinvestment in short-maturity bonds, raising long-term interest rates and benefiting the country's large and restless population of savers for whom QE has been economically damaging.

To an extent this has already happened since 2017 when investment in assets yielding below the ECB deposit rate of minus 0.4% was allowed. This has led to a rapid fall in the weighted average maturity of Germany's public sector purchase programme bond holdings.

The ECB is unlikely to announce a decision on these issues when the governing council meets later today. The December meeting will be the crucial moment for providing guidance on the future of QE. This will be an important market-moving moment. The sooner the ECB clarifies the rules, the better.

Additional purchases via reinvesting redemptions of other countries' maturing bonds will add to the strain. The ECB has not yet decided – let alone announced – how it will conduct reinvestments. The governing council may yet decide to increase the issuer limit to avoid this constraint. However, this is likely to meet political resistance.

A more positive effect of the 'de facto' capital key deviation reflects the position in Italy. The required drop in ECB holdings of Italian bonds will be lower than it would be using the de jure capital key allocation.

Italian bonds will have been overpurchased by more than €26bn by end-2018 according to the country's strict capital key share. To match Italy's reduced 2019 capital key, the Banca d'Italia would have to reduce its holdings of Italian debt by almost €45bn. However, the need to make up for under-purchases in countries with smaller bond markets means that this figure is closer to €21bn.

While still a large reduction for a country planning to expand debt issuance in the next budget, the impact will be less severe than it might otherwise be.

Italy may complain that its capital key share will fall to 16.6% from 17.5% next year. Yet the actual share of its bonds that will be purchased in the ECB's reinvestment is likely to be closer to 17.8% – larger than its current de jure figure, but smaller than its current de facto share of 18.8%.

Many other technical issues need to be clarified, for example on changing the maturities of reinvested bonds.

Replacing maturing Italian debt with longer-dated securities would help flatten the yield curve and be more stimulative than reinvesting in bonds with a similar maturity profile. This could strengthen the capital position of Italian banks, which own large shares of Italian government debt, and which should benefit from rising prices.

Theoretically such flexibility would also allow German reinvestment in short-maturity bonds, raising long-term interest rates and benefiting the country's large and restless population of savers for whom QE has been economically damaging.

To an extent this has already happened since 2017 when investment in assets yielding below the ECB deposit rate of minus 0.4% was allowed. This has led to a rapid fall in the weighted average maturity of Germany's public sector purchase programme bond holdings.

The ECB is unlikely to announce a decision on these issues when the governing council meets later today. The December meeting will be the crucial moment for providing guidance on the future of QE. This will be an important market-moving moment. The sooner the ECB clarifies the rules, the better.